So the Large Hadron Collider has finally been switched on; very much later than originally scheduled, but then it’s a staggeringly big, complicated, expensive piece of kit, so it was just as well to make sure they got it right first time.

It really is pure geek porn: the sheer size of it, just as a piece of machinery; the amount of energy it’s going to throw around; the mind-boggling degree of precision required to smash protons into each other at nearly the speed of light; the amount of computing power it needs to process the data produced. And of course the fact that all this money and expertise and time is being expended simply to advance our knowledge: it is the purest of pure science. It makes me happy every time I think about it.

With all the publicity surrounding the LHC, I’ve been thinking how sad it is that so many people find science boring or scary or completely alien. Of course you can get through life without ever having felt the joy of science, just as you can get through life without ever having understood why some people place such a high value on poetry, or art, or music. But it seems a bit of a waste.

I guess a lot of people start without much natural sympathy for the subject anyway, and then school finishes the job by putting them off for life. I found science lessons at school pretty deathly myself, and I was interested. And I don’t really know what the answer is.

Part of the problem is perhaps that science is presented in school as a very static entity: there’s no sense of it as a dynamic process, a gradual painstaking effort to build up knowledge, with dead ends and wrong turnings and leaps of genius. I’ve always found science more interesting with a bit of historical context; it humanizes science to learn about Newton and Darwin as people. It’s also easier to appreciate the brilliance of some particular insight if you know what people thought beforehand, and why they realised they were wrong.

For example, Newton’s laws of motion and gravitation are very dry when you learn about them at school as a way of predicting the behaviour of falling objects and billiard balls and pendulums. They gain some resonance when you understand that, for the first time, Newton tied the whole universe together. The significance of the famous apple that Newton saw fall from a tree is not so much that he came up with a way of explaining falling apples: it’s that he realised that the apple falling to the ground and the moon orbiting the Earth are the same thing. The same simple set of equations can be used to explain both.

But the trouble with all this human colour and historical context is that it is window-dressing. It’s like trying to teach science by discussing scientific issues in the news: it may make for a lively discussion, but that isn’t enough unless you manage to teach the science itself. Students need to feel the power of theory; of abstract thinking, of reductionism. And I think that’s quite a difficult thing to teach.

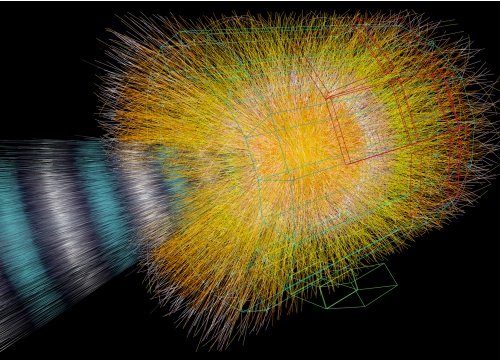

» The pictures, both stolen from CERN, are simulated images of collision events; the first is a proton collision creating a microscopic black hole, the second is a lead ion collision.