I went along to the viewing of a sale of Impressionist and modern art at Christie’s in London.

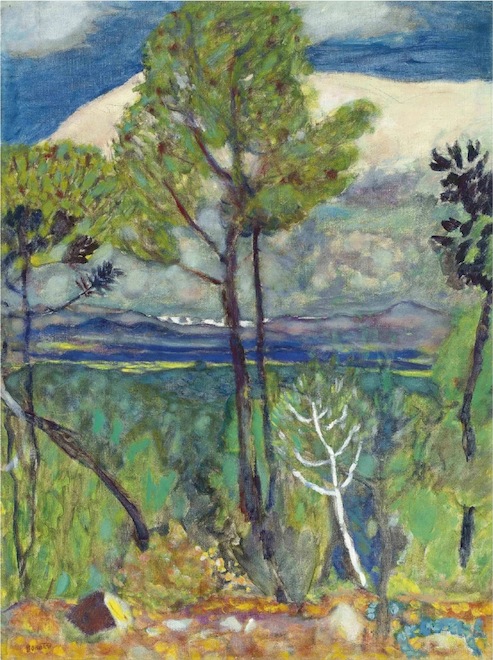

It’s always quite interesting going to see paintings at auction houses rather than the big public art galleries where I see most of my art. For a start, there’s the fact that everything has a price on it; of course they’re only estimates, but they give you a general sense of what’s hot and what isn’t. The trends are somewhat predictable, of course; a large, stylistically distinctive painting by a Very Famous Artist goes for a lot more than a small, sketchy painting by a someone slightly less famous. The painting above,Les pins, bord de mer by Pierre Bonnard, is estimated at £150,000 – £250,000.* Which is quite a lot of money by most standards, but seems pretty modest compared to the £17,000,000 – £24,000,000 for some Monet waterlilies.

Actually, though, it’s not surprising that a large painting by Monet of his most iconic subjects is worth a fuck of a lot of money. If you’re a Russian oligarch and you put that on your wall, people are going to walk into the room and know you’ve spent shitloads of money on it.

In some ways it’s the lesser paintings which say more about the madness of art prices. Not even great artists produce masterpieces every time they pick up a brush, and there’s a plentiful supply of little sketchy paintings and ones which don’t quite work; paintings which look like they could have been done by any random weekend painter, but which go for hundreds of thousands of pounds.

A couple of other thoughts about the auction house experience. I quite like the fact that people feel free to talk, to have normal conversations at a fairly normal volume; and indeed to use their mobile phones. The sanctified hush of public art galleries, with everyone whispering to each other, can be a bit deadening.

And however artistically radical a painting may have been when it was new, seeing it surrounded by the sheen of money in an upmarket auctioneers really does strip away any last hint of anti-establishment.

* Update: it actually went for £337,250, fwiw.