This is my book from Brunei for the Read The World challenge. Brunei is one of the countries which is particularly difficult to find books from; so when I found this self-published ‘science fiction thriller’ on Amazon I snapped it up.

It is the story of A’jon, a man chosen to be Brunei’s first astronaut because of his expertise in cryptography. His mission is caught up in Dramatic Events, and [SPOILER ALERT, I guess], he is put in suspended animation for 500 years, floating in space, before being revived and brought back to earth where his cryptographic expertise once more gets him involved in Dramatic Events and [even more SPOILERY] he saves the world.

Sadly it’s not very good; it’s the kind of book that makes people suspicious of self-publishing. This is a sample of the clunky prose and dialogue:

A’jon grabbed his fork and drove it into the middle of the plate. He twirled the fork several times until he grabbed the right amount, and then lifted it without a strand hanging and put it in his mouth. He was careful to not drop any of the sauce and get his new clothes dirty. His tongue reacted instantly to the food. “Mmm, that’s delicious!” he said while chewing the first bite.

“Makes me proud to be an Asian. Pasta originated from China before it was brought to Italy. It’s amazing how the combination of water and wheat can form such remarkable dough. You can mold it into almost any shape you like — fusilli, tagliatelle, ziti, rice vermicelli.”

With each bite, A’jon wrapped as much of the cheesy sauce round his tongue as he could before the flavor disappeared.

I’m resisting the urge to really pull this book apart; because it’s a soft target, and also because its flaws are essentially innocuous. It’s not particularly annoying or offensive, it’s just badly written.

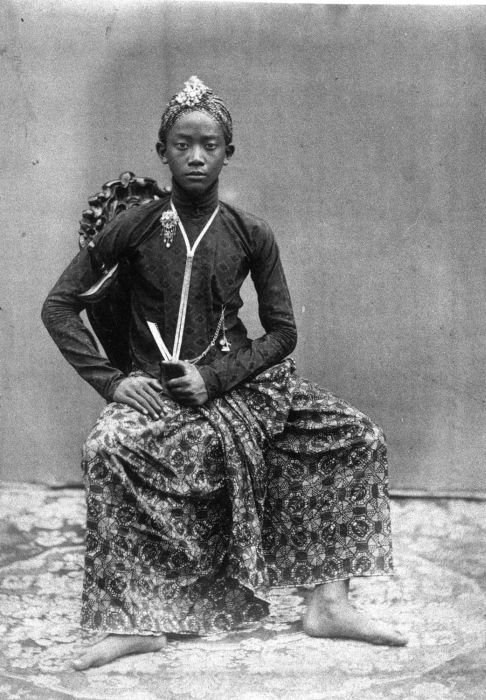

» The picture is of the teapot roundabout in Kuala Belait, Brunei. It is © Rachel Walker and used under a by-nc-sa licence.