I knew that To Sir, With Love was a book about a black Caribbean man struggling with racial prejudice in 1950s London, so I was quite amused that the opening — his description of travelling on a bus full of East End women — reads so much like a white colonial Briton describing the natives of a third world country. It’s the combination of effortless cultural superiority and an anthropological eye.

The women carried large heavy shopping bags, and in the ripe mixture of odours which accompanied them, the predominant one hinted at a good haul of fish or fishy things. They reminded me somehow of the peasants in a book by Steinbeck – they were of the city, but they dressed like peasants, they looked like peasants, and they talked like peasants. Their cows were motor-driven milk floats; their tools were mop and pail and kneeling pad; their farms a forest of steel and concrete. In spite of the hairgrips and headscarves, they had their own kind of dignity.

They joshed and chivvied each other and the conductor in an endless stream of lewdly suggestive remarks and retorts, quite careless of being overheard by me – a Negro, and the only other male on the bus. The conductor, a lively, quick-witted felllow, seemed to know them all well enough to address them on very personal terms, and kept them in noisy good humour with a stream of quips and pleasantries to which they made reply in kind. Sex seemed little more than a joke to them, a conversation piece which alternated with their comments on the weather, and their vividly detailed discussions on their actual or imagined ailments.

There was another particularly fine example of the type later on the book:

I did not go over to him: these Cockneys are proud people and prefer to be left to themselves at times when they feel ashamed.

It could be a conscious literary decision to subvert expectations, but firstly Braithwaite doesn’t particularly strike me as that kind of writer — he’s generally pretty direct — and also I can imagine a white British writer with a similar educational background writing in much the same way; like Orwell’s representation of the proles in 1984.

In other words it’s partially a class thing; Braithwaite was from a very educated background; both his parents went to Oxford, which I assume was pretty rare in Guyana at the start of the C20th, and he studied in New York before serving as a pilot in the RAF during the war and then doing a Master’s degree at Cambridge. But then race is always partially about class. The class structure is one of the ways that racial status can be monitored and enforced. And it was only because of Braithwaite’s race that he was doing what no similarly educated white Briton would be doing: working as a teacher in a grotty East End secondary school. He was rejected from all the engineering jobs which he was better qualified to do, often on explicitly racial grounds in the days when it was legal to tell people that to their faces, and fell into teaching because it was the only option available.

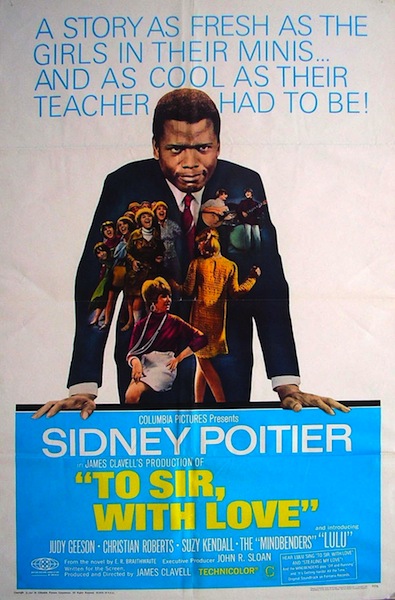

So that’s the set-up: educated, well-dressed black man takes a job teaching in a run-down East End school full of problem teenagers. And if you’ve ever seen a movie where an inspiring teacher goes to work in a deprived inner city school, you pretty much know how the rest of it plays out: he is stern but wise and passionate, and he overcomes their initial hostility and prejudice to teach them the value of education and good manners, and above all he teaches them self respect. And he in turn learns his own lessons, about not being such a snobby prude (although he doesn’t learn the lesson that if you’re a grown man writing about fifteen and sixteen year old girls, there are only so many times you can mention their breasts before it starts to seem a bit creepy).

I’m being a bit glib; there is a lot that’s interesting about this book, and it’s well written. But when I say it’s like a Hollywood movie: it really does read like that. And of course you wonder if it’s too good to be true. Clearly he is an impressive man, and I can believe he was an inspiring teacher, and I expect the broad outlines are all true… but for something which claims to be non-fiction, it just seems like it was written by someone who was willing to burnish the truth for the sake of a good story.

To Sir, With Love is my book from Guyana for the Read The World challenge. I seem to have been harder on it than I really intended. I think it’s probably fairest to say it’s a good book which has aged badly. But there’s still plenty to like about it.