This is a properly remarkable book. It is, as the subtitle explains, ‘The Autobiographical Writings of a Crown Princess of Eighteenth-Century Korea’. Lady Hyegyŏng* was married into the royal family; she married Sado, the Crown Prince, when they were both nine years old. Sado never became king — he was executed in 1762 at the age of 27 — but their son inherited the throne as King Chŏngjo. Remarkably, Hyegyŏng outlived him as well, and three of these four ‘memoirs’ were written after 1800, during the reign of her grandson King Sunjo.

So she had a long and eventful life, and it makes for fascinating reading. It’s sometimes a little difficult keeping track of who’s who: there’s a large cast of characters, the court intrigues are confusing, and the family relationships are complicated by the fact that the kings and princes have children by multiple women; some wives, some consorts. And because I’m unused to Korean names they all sound a bit the same to me. But it has a list of characters and some family trees, which helped.

The other complication is that these are four separate memoirs which overlap with each other. So the first (‘The Memoir of 1795’) is closest to the modern idea of a memoir, starting with her childhood and covering most of her life, but it carefully avoids any details about the single most important event: the execution of Prince Sado. The execution of the crown Prince by his father is so politically charged that she only alludes to it in the vaguest terms. Then the memoirs of 1801 and 1802 are more directly political; public advocacy aimed at defending the reputation of her father and brothers, who had fallen out favour after the death of Chŏngjo. And in the Memoir of 1805, she finally returns to the story of Sado, explaining that 40 years of silence has allowed false versions of events to take hold, and she believes it is important to tell what really happened.

And the story of Prince Sado is extraordinary. I don’t want to give all the details; I’m sure I enjoyed this book more because I was surprised and shocked by it. But the central fact of his execution is this: he was suffering from some kind of mental illness, and it progressed to the point that he was thought to be a credible threat to the life of the king. But because he was royal, custom forbade any method of execution that would disfigure the body, and poison would have implied he was a criminal; so he was shut into a rice chest and left to starve to death.

As you might imagine, this event traumatised the entire royal family in various ways; hence it being taboo to talk about it for four decades after it happened.

But although it was an extreme example, it also gives a hint of the brutality of court life. There are an awful lot of people who get banished to remote islands, or tortured or executed; usually for saying something which is perceived to be disloyal. That ‘disloyalty’, at least at this cultural distance, often seems to be based on terrifyingly slight nuances of speech.

So I found it fascinating as a portrayal of a time and place, and the whole story is positively Shakespearean.† But it is also much more readable than you might expect. If you skipped the two middle memoirs it would be a positive page-turner; not that they aren’t interesting, but they are harder work.

The Memoirs of Lady Hyegyŏng is my book from South Korea for the Read The World challenge. I’d still like to read some contemporary Korean fiction, it seems like a really interesting country at the moment. But this caught my eye, and I’m glad I read it. It’s fascinating.

*Or Hyegyeong, in the newer Revised Romanization which is the official standard since 2000 (this is all according to Wikipedia, obviously). Similarly, Chŏngjo = Jeongjo, etc. The book was published in 1985, so it uses the older McCune–Reischauer system.

†Genuinely, it was reading books like this, whether about historical kings or modern dictators, that helped me see Shakespeare’s plays in a new light; I always read them as psychological studies, family dramas that just happen to be set against a more glamorous background. But life in the court of an absolute ruler, like Stalin or King Yǒngjo or Elizabeth I, is really not a normal family situation. Unfortunately I only arrived at this insight after I finished studying Shakespeare at university.

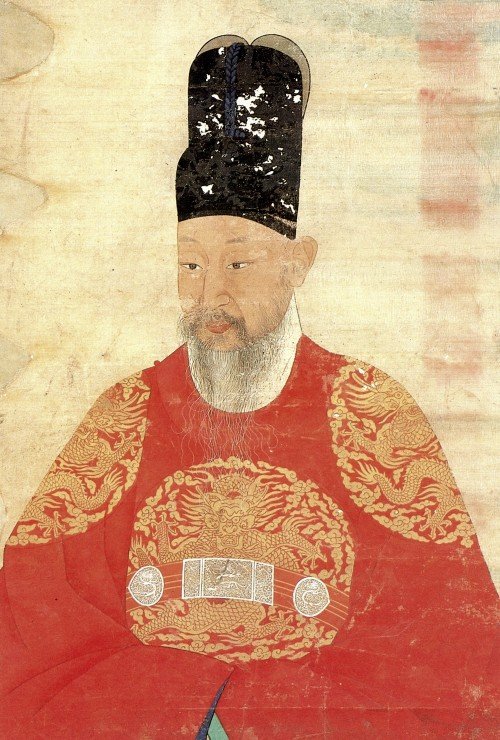

» The portrait is of King Yǒngjo, Prince Sado’s father. I took it from Wikipedia.