I have been following events in north Africa closely, both via the usual media outlets and Twitter (see, for example, Andy Carvin’s one-man newswire for all the latest rumours swirling around). But I haven’t said much about it on this blog because, well, it’s a complicated subject of which I am ignorant.

It has often been enthralling, even so. The spread of protests from country to country, the ebb and flow between protestors and their governments: at times like this, live round-the-clock news coverage actually makes sense. Egypt had almost the perfect revolution for a spectator; large photogenic crowds, plenty of reporters on the scene, a hint of euphoria, a frisson of danger to add some spice, and not, in the end, too many casualties. Libya has been a darker experience; the more brutal response by the regime and the effective news blackout just producing a swirl of horrifying but unconfirmed rumours swirling around on Twitter.

There have already been some extraordinary moments, like the Wael Ghonim interview,or the incredible celebrations in Tahrir Square after Hosni Mubarak’s resignation. Or last night’s speech from Saif Gaddafi, which was so weirdly rambling and unfocussed that the conspiracy theory, that he was just buying time for his father to flee the country, almost seems like a plausible explanation.

And it has been making me think about the way we talk about foreign policy. Because when a popular revolution peacefully overthrows the dictator of a brutal autocratic police state with a habit of torturing its own citizens, it would be nice to be on the side of the protesters. Which makes it slightly awkward that our governments have spent decades supporting the dictator. And it’s not just Hosni Mubarak; it’s Bahrain, it’s Saudi Arabia; even Gaddafi had managed to rebrand himself from mortal enemy of the West to someone we can do business with. And there’s the awkward fact that we supported Saddam Hussein until it stopped being convenient. At least we can say we definitely don’t support the Iranian theocracy… but then that did come into being after a popular revolution against a brutal dictator who, almost inevitably, was someone we did support.

The deeply murky nature of our foreign policy is hardly news, of course. What I find so frustrating is the way that we talk about it, the way that governments feel the need to gloss over all the unpleasant details right up until the moment when the regime falls, and we are shocked, shocked to discover that Hosni Mubarak was a revolting dictator all along.

It would just be refreshing sometimes to hear a politician stand up explicitly spell out the logic:

Yes, we know that in supporting Hosni Mubarak we are propping up a brutal police state. But look around at the other countries in the region: Sudan has had decades of civil war and genocide. Eritrea and Ethiopia have been at war. Somalia is a failed state. Libya and Iran are even more repressive states and supporters of terrorism. Yemen serves as a base for Al-Qaeda. And so on. So we take the position, on balance, that supporting a nasty dictator is a reasonable trade-off for decades of stability and no war with Israel.

Because that argument may be right or wrong, but I don’t think it’s stupid. I don’t think it’s even outrageously cynical. Because foreign policy is a fairly blunt instrument. Mubarak’s regime might not have been our ideal choice for the kind of government Egypt should have, but then we don’t really get to choose. We certainly don’t get to control the internal policies of the country; all we can do, presumably, is to look at the government in place, weigh up the possible alternatives, and decide to support them or not.

Of course it’s a bit more nuanced than that — there are different degrees of support, there are various pressures we can apply — but short of invading, which is hardly a panacea, we’re pretty limited in what we can do. Foreign policy has to be deeply pragmatic because the range of choices is so limited.

I’m not suggesting that foreign policy has to be horribly cynical, although it clearly often is. It’s just difficult. Even if you don’t allow self-interest to trump human rights. Even if your only concern was the well-being of the people of north Africa and the middle east, you’d still probably end up supporting a few dictators. But it would just be nice if politicians would be a bit more open about it, a bit more explicit about the bargains they are making. A bit less diplomatic, in fact.

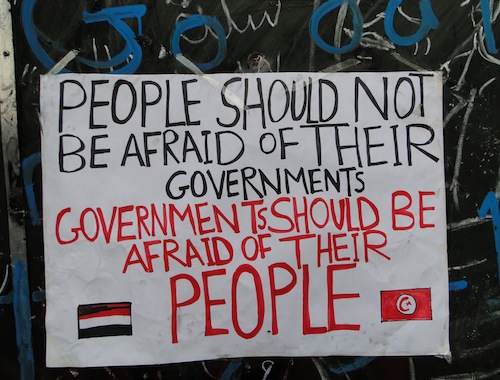

» Demonstrators Praying and Riot Police and People Should Not Be Afraid of Their Governments, Governments Should Be Afraid of Their People are © Ramy Raoof and used under a CC by licence. The shot of protestors in Tahrir Square in from Al-Jazeera.

2 replies on “Egypt, Libya, foreign policy and honesty”

It would be easier for pols to be open about it if voters were all as thoughtful as you. But they aren’t; a lot of them don’t do nuance, and certainly don’t do difficult. In fact, many don’t do foreign at all, except to say that they don’t want it here. “How it plays in Peoria” has a worrying impact on public political discourse.

Yes, there is that. And also, there are, um, diplomatic reasons for using diplomatic language: having decided to support some dictator as the least bad choice available, it makes sense to actually support them in your public statements as well.

Still, you have to suspect that it breeds a culture of worldly cynicism among the professional diplomatic classes at the Foreign Office and the State Department, where being hard-nosed and pragmatic becomes seen as a sign of professionalism. And, conversely, where worrying too much about things like human rights starts to be a sign of softness and amateurism.