I made plans to go birding yesterday in the expectation it would be sunny again; in the event it was grey, overcast and drizzly.

But I did see one swallow.

I made plans to go birding yesterday in the expectation it would be sunny again; in the event it was grey, overcast and drizzly.

But I did see one swallow.

Well, not actual summer, obviously. But it has been a week of glorious spring sunshine here, and I’ve been out and about enjoying it and doing some birding.

On Monday I failed yet again to see Lesser-spotted Woodpecker in Richmond Park *shakes fist in general direction of south-west London*, but that was more than made up for by two birds. One was a woodcock — a sign that winter hasn’t quite left us yet, because they certainly don’t breed in Richmond. It was the classic brief view of it appearing from the leaf litter, flying a short distance and disappearing again, but it was a lifer for me so yay.

The other was the duck I used to illustrate my last post. I took the picture because it was an obviously odd-looking Tufted Duck, presumably a hybrid but I wasn’t sure quite what; turns out to be Tufted Duck × Ring-necked Duck. Which is cool, because Ring-necked Duck is an American species and a bit of a rarity in Europe, while Tufted is a European species and occasional visitor to North America… but like an anatine Romeo and Juliet, one pair obviously overcame the obstacles. If, that is, the parents were wild birds. I saw a black swan yesterday, and I’m quite certain that it didn’t fly here all the way from Australia. Not to mention the Mandarin Ducks, Egyptian Geese and Ring-necked Parakeets that breed in Richmond Park.

Still, it was an interesting bird. And the first time in a while, incidentally, that I regretted not having a paper field guide with me as well as the iPhone one, but fortunately the photos I took were good enough to let me work it out later.

And yesterday I had a good day up in the Lee Valley. I kind of hoped I might see a migrating Osprey, which didn’t work out. But I saw about eight species of duck, including Goldeneye, had a good view of a Water Rail, and the Chiffchaffs and Cetti’s Warblers were singing. And I saw my first Sand Martin of the year (that’s Bank Swallow if you’re American), and the best bird was a Pink-footed Goose in among the greylags.

And lastly, on Wednesday I went for a walk with a friend on the South Downs, and the skylarks and meadow pipits were singing, which was nice, but the most surprising thing was to suddenly hear a distinctive groonk groonk — raven!

I still think of ravens as birds of the really wild places; Welsh mountain tops, Scottish moors. Which they were, when I started birding twenty years ago. But actually they’re one of the most adaptable species in the world, living everywhere from deserts to the high Arctic. The fact that, when I was a child, you didn’t see them circling high over rolling farmland in southern England: that was a historical accident. It was the result of them being wiped out by gamekeepers and farmers. And now they are protected, they are coming back; like the buzzards, the peregrines, the sparrowhawks. And they are a joy to see.

It’s that time of year again. Time for some citizen science! I got off to a great start with two siskins, and ended up with a respectable 17 species:

Blue Tit × 6

Great Tit × 4

Long-tailed Tit × 3

Chaffinch × 5

Greenfinch × 7

Goldfinch × 3

Siskin × 2

Dunnock

Robin

Blackbird

Nuthatch × 2

Woodpigeon × 2

Feral Pigeon × 4

Collared Dove

Great-spotted Woodpecker × 2

Green Woodpecker

Magpie × 2

Collared dove is a new one for the BGBW; it’s a species that only turns up in the garden very occasionally. As always a few regular species failed to show: coal tit, goldcrest, jay and most surprisingly, ring-necked parakeet. But it was still a good year.

There was a shoveler at the local park the other day, which I think is probably the first I’ve seen there and a patch tick. ‘Patch tick’, for the non-birders among you, meaning a new addition for my patch list, i.e. the list of birds I’ve seen in my local patch — in my case a not very well-defined area consisting of anywhere within about half an hour’s walk of the front door. Not exactly prime birding territory, but it has a few suburban parks and a bit of woodland in it.

Birders tend to keep a lot of lists: some of them lend themselves to being taken quite seriously, like a British list or a life list. Those lists are effectively a way of keeping score over a whole lifetime of birding, and those are the ones which attract the serious obsessives. But the great joy of the more casual lists — the garden list, the patch list, the London list, or whatever — is the way they can turn a rather ordinary bird into an exciting event. Like that shoveler: it’s an attractive but common and easily seen duck, and I’ve seen dozens of them this year already… but in the park it’s a patch tick. A tiny unexpected triumph in an otherwise mundane stroll around the park.

I don’t actually keep a patch list written down anywhere. I’m not much of a record keeper when it comes to birding. My patch list, like my garden list and my London list, is a slightly fuzzy mental one. The only written lists I have are British and European; I don’t even have a proper life list, though I could more or less reconstruct one from various notebooks. Perhaps that would be a good project.

Anyway, today I went to the London Wetland Centre and I added two birds to my British list and one to my life list. The one I’ve seen before is Scaup, a kind of duck which I saw in Japan many years ago; the new one is a streaky brown finch called Common/Mealy Redpoll.

Which is actually a new species; not just new to me, new as in it isn’t in the field guide. Redpolls were split into two species, Lesser Redpoll and Common Redpoll, having previously been distinct subspecies. The Common Redpoll is what British birders used to call ‘Mealy Redpoll’, the paler, greyer, slightly larger redpolls from the continent which sometimes turn up here in winter among the more common Lesser Redpolls. As you can imagine, the differences are subtle, and I can’t say I felt immediately confident about the ID; but for once I had a good eye-level view of them instead of their undersides silhouetted against the sky, and in a flock of birds which were warm brown in tone there was one which was distinctly different looking, paler and greyer, and I thought, well, if I’m not going to claim this one I might as well give up now.

It’s odd how much it feels like a moral issue. Believe me, I’m well aware that no-one else cares about my rather paltry life list. But to add something to it without being sure; well, that would be cheating. So when I see one of these more difficult species, I really do fret about it, and usually I reluctantly don’t claim them. I tried to persuade myself I’d seen Common Redpoll last winter but just couldn’t quite swing it.

» Anas clypeata | Shoveler is © Muchaxo and used under a CC by-nc-nd licence.

Full title: Life Ascending: The Ten Great Inventions of Evolution. The ten ‘inventions’ are: The origin of life, DNA, photosynthesis, the complex cell, sex, movement, sight, hot blood, consciousness and death. Lane explains how each of these work and how they evolved, at least as far as current knowledge can take us — which in some cases, like the origin of life, is apparently rather further than I had realised. The consciousness chapter, if you’re wondering, was rather less persuasive.

What sets this book apart from most popular accounts of evolution is that Nick Lane is a biochemist rather than, say, a palaeontologist or an ethologist. So this is a book which focuses on evolution at the micro level: it’s all biochemical pathways and enzymes and the genes which code for them. This is the real nitty gritty of how evolution works, how it actually achieves things; but it’s also the stuff which I generally find is a complete headfuck. No matter how many times I have read accounts of the inner workings of a cell over the years, it just doesn’t stick.

So it is not a small compliment to say I found this book was not just full of new and interesting information, but also managed to be clear, engaging and enjoyable. I still ending up having a long pause halfway through, and I’ve already forgotten a lot of it, but I enjoyed it as I read it.

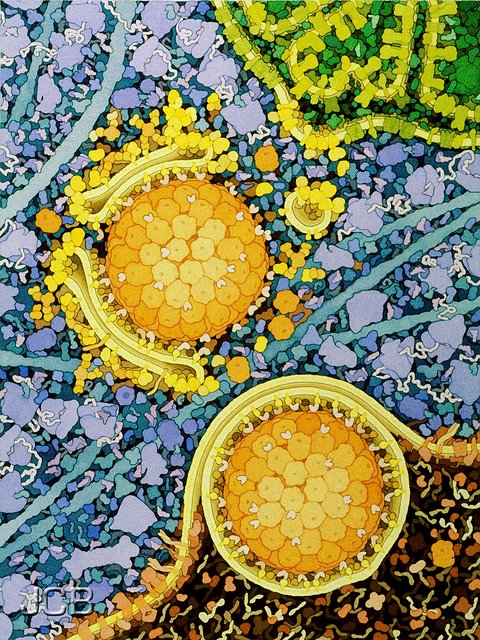

» The picture is Cytoplasm to vacuole targeting from the Journal of Cell Biology, used under a CC by-nc-sa licence. Picked because it’s a striking image rather than because it’s relevant in any way beyond basic thematic appropriateness.

‘The cytoplasm to vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway uses Atg11 to direct Atg9-containing membrane from mitochondria (top right) to forming autophagosomes (center) before eventual fusion with the vacuole (bottom right). Original painting by David S. Goodsell, based on the scientific design of Daniel J. Klionsky. (JCB 175(6) TOC1)’

I made my annual trip to the Wildlife Photographer of the Year exhibition at the Natural History Museum. I thought it was particularly good this year. Here’s a pleasing and particularly original long-exposure photo of a gannet colony by Andrew Parkinson:

You can see all the winners on the NHM website, but obviously it’s better to go and see the pictures blown up nice and big on lightboxes if you have the chance.