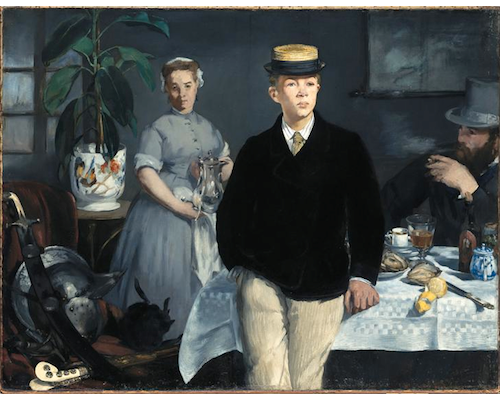

This is Le Déjeuner dans l’atelier by Édouard Manet.

I don’t have much to say about it. Good though, innit.

This is Le Déjeuner dans l’atelier by Édouard Manet.

I don’t have much to say about it. Good though, innit.

This is The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli by Carlo Carrà. To quote Wikipedia:

The subject of the work is the funeral of Italian anarchist Angelo Galli, killed by police during a general strike in 1904. The Italian State feared that the funeral would become a de facto political demonstration and refused the mourning anarchists entrance into the cemetery itself. When anarchists resisted, the police responded with force and a violent scuffle ensued.

I saw it in the Tate’s Futurism exhibition last year, and thought it was pretty striking, but looking at it now I find myself strongly reminded of a lot of images I have seen in the news recently: that angry claustrophobic mass of figures, the horses, the batons.

Over the past few weeks we’ve had violent confrontations between protestors and police on the streets of London, we’ve had protestors closing down high street shops in protest against tax-avoidance by big business, we’ve even had Mrs Prince Charles poked with a stick by a group of people chanting ‘off with their heads.’

And we’ve even had the word ‘anarchist’ being thrown around, a word which seems as dated as Futurism itself. I don’t know how many of those who have been on the news smashing windows and setting fire to things would say they were anarchists, and I don’t know what they mean by it. But then perhaps anarchism has always been a mood as much as a political ideology. And yes, I know, political theorists have devised versions of anarchism which are more sophisticated than the caricature; but still, that wish to break down the overarching structure of society is a remarkable thing. You have to think that the world is very broken indeed to believe that throwing all the pieces up in the air is likely to make it better.

But then whether many people in the UK are ‘real’ anarchists is hardly the point; what matters is that a lot of people are angry. And not just in Britain. Are there enough of them, are they angry enough, to have a powerful impact? And for better or worse? These are interesting times.

I’m feeling ill today — perhaps I managed to poison myself with homemade chicken soup — so I thought perhaps I’d see if could find a painting with a medical theme. So here’s a cracker by Hieronymus Bosch, known as The Extraction of the Stone of Madness or The Cure of Folly.

All that amazing Gothic writing apparently says

Meester snijt die keye ras

Mijne name Is lubbert das

Which apparently means ‘Master, cut away the stone / my name is Lubbert Das’, Lubbert Das being the name for a fool in Dutch literature.*

It is presumably allegorical of something, but The Prado and Wikipedia disagree about what it means. I don’t think I care, though. It’s a striking image, and that gold calligraphy is just astonishing.

There are some great self portraits in the canon — Dürer, El Greco, Van Gogh, Van Eyck, all those Rembrandts — but I’m not sure any of them is as fabulous as this one by Diego Velázquez:

It’s like the world’s greatest publicity photo.

I think it’s interesting how much particular styles and periods can go in and out of fashion. The fact that whole artistic movements can gain and lose popularity for no simple reason serves as a valuable warning if you ever start thinking that your taste is in any way objective or reliable.

Nicolas Poussin is a painter of high neo-classicism; a genre which is about as unfashionable as it is possible to be.

Some of the reasons why a painter like Poussin is unfashionable are clear enough: for example, people are much less familiar with all the Greek and Roman references. Others are easy to articulate but less easy to explain: I think it’s a fair generalisation that history paintings, and narrative paintings more generally, are unpopular today. But it’s not transparently obvious why that should be true.

This painting, A Dance to the Music of Time, is more approachable than many of his works; compared, for example, to The Rape of the Sabine Women. It’s more intimate in scale, and it’s sort of allegorical or symbolic rather than properly narrative. Both of those things make it seem less stagey. Still, it’s not the kind of painting that would pull a lot of punters through the doors of a London gallery in 2010.

But fashions change. Maybe in twenty years time, Poussin will be THE hot ticket, and Van Gogh will be regarded as terribly old fashioned and déclassé.

Fashion aside, there is one thing about this painting which makes it remarkable: the whole surface is covered in thumbprints. When the paint was still wet, Poussin covered the surface of the painting with the imprint of his own thumb. Why did he leave his mark on it in this way? No one knows.

2AM tonight is the start of the third Ashes test, with England one-nil up in the series and with the opportunity to ruthlessly grind Australia into the dust in the same way the Aussies have done so many times to us over the past 30 years.

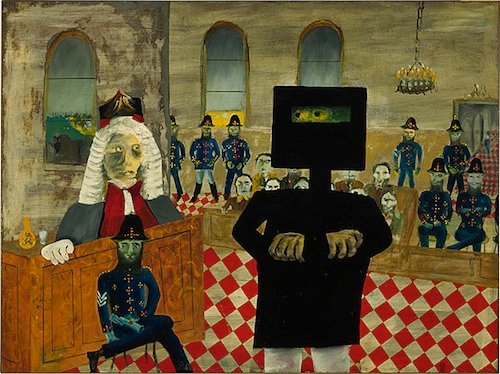

So it seems fitting to pick an Australian painting; this is The Trial, from Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly series. Ned Kelly was the Australian outlaw and folk hero, famous for his home-made suit of armour.

Part of his folk hero status comes from the fact that he was, according to one interpretation, rebelling against the oppressive British colonial power. Which brings us back to the cricket, since the particular best-of-enemies edge that surrounds the Ashes is partly because of the frisson that comes with a match against the former colonial power.

The Ashes got their name in 1882 when Australia beat England in England for the first time, and the Sporting Times printed a mock obituary announcing the sad death of English cricket: ‘the body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia’. Which is, incidentally, just two years after the execution of Ned Kelly.

Going back to the actual painting: I was interested to read that Nolan was very influenced by Henri Rousseau. Because I reckon that Rousseau actually wanted to be a proper painter in the classical academy tradition, but having taught himself to paint in his spare time as an adult, he just wasn’t technically capable of that style of painting. The paintings he did produce are beautiful — he had a great eye for design and colour — but they are in a naive style because that was all he could do. Which is something rather different from the self-consciously naive style of a painter like Nolan.

Anyway, there are a lot more paintings by Nolan (and indeed other Australian artists) on the National Gallery of Australia website, if you’re interested.