A link from C. Dale Young sent me to this article which is rather unflattering about a scheme to promote poetry in Seattle. What got me going, though, was this, from someone defending the scheme in the comments:

On comprehending poetry: you say “Poetry, by its very definition, is a difficult thing to write and to comprehend.” Certainly you can’t mean this, or perhaps you are simply uninformed. Since Mallarmé and especially since TS Eliot, perhaps, poetry’s hallmark is to be difficult, but again this is recent history given the history of bards: the Odyssey was the equivalent of a pulp fiction bestseller or action-adventure flick, ditto Beowulf and the Eddas. The Canterbury Tales, the Divine Comedy and Paradise Lost were intended to be blockbusters, not PhD theses. Shakespeare was not looking to mystify the objects of his love sonnets, nor is the work of Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, William Carlos Williams, Langston Hughes, Adrienne Rich, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Ntozake Shange, Sharon Olds, Saul Williams, Li-Young Lee or in fact most poets worth their salt supposed to be incomprehensible or even that difficult.

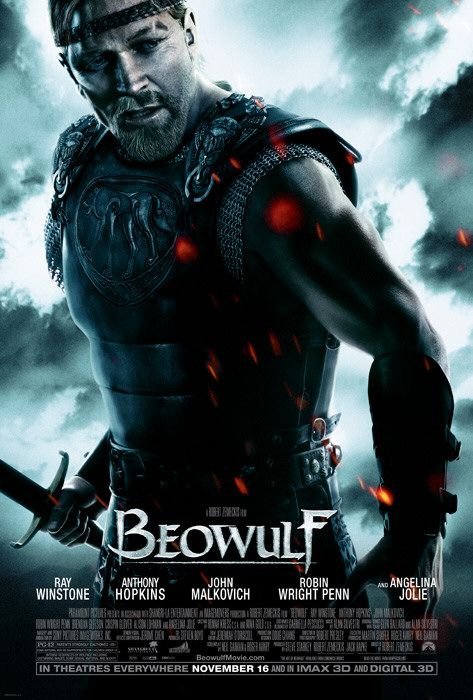

Now I agree with the basic point that difficulty is not an essential quality of poetry. But as someone with an interest in Anglo-Saxon poetry, I notice references in the media, so I have encountered this idea before, that Beowulf ‘was the equivalent of a pulp fiction bestseller or action-adventure flick’.

It is a fucking ridiculous comparison.

One version of it is based, as far as I can tell, simply on the kind of story it is: Beowulf is about a buff warrior-hero type who goes out and fights monsters, so it must be the Dark Ages version of Die Hard or Independence Day. Now I happen to believe this is a profound misreading of the poem, at least until someone makes a version of Die Hard which concerns itself deeply with the fragility, briefness and futility of human existence, or a version of Independence Day where the aliens win at the end.

But to properly try to refute that argument would be a difficult exercise, hedged around with qualifiers and uncertainty, because anyone who claims to know why Beowulf was written, who it was written for, how it was received or what kind of place it had in the culture is talking out of their arse.

Do you know how many surviving copies there are of long narrative Anglo-Saxon poems on non-Christian mythological themes? One. Beowulf. We assume that it is the only survivor from a rich oral culture of similar poems that were either never written down or have been lost — but we don’t know. And we certainly don’t know if Beowulf is a typical example, or how much it was changed when it was written down… or anything much at all, really.

And as for the statement that ‘the Canterbury Tales, the Divine Comedy and Paradise Lost were intended to be blockbusters, not PhD theses’: Jesus wept.

I mean Chaucer, maybe sorta kinda; Dante I don’t know much about, although even in C14th Florence there must have been more populist options available than the theological epic; but Milton? Seriously? He’s your example of poetry not having to be difficult? There aren’t many poems in English more self-consciously literary, less populist and more stubbornly unwilling to make life easy for the reader than Paradise Lost.

I think what annoys me so much isn’t the inaccuracy of these comparisons: it’s the fact that anyone wants to make them at all. I understand the wish to resist the ghettoisation of poetry as an recondite and überliterary artform. And it’s true that there is a long and valuable tradition of popular, accessible poetry, much of it ephemeral but some of real merit. But to compare Homer and Beowulf to action movies, or call the Divine Comedy a blockbuster, and think you’re doing them a favour… I just don’t get it.