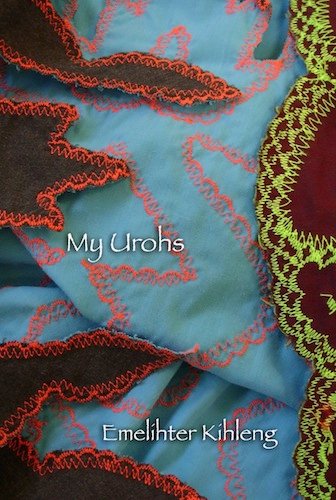

This is an interesting one: a piece of oral poetry, transcribed from a performance by a griot*, Nouhou Malio, in Niger. To quote the introduction:

The Epic of Askia Mohammed recounts the life of the most famous ruler of the Songhay empire, a man who reigned in Gao, an old city in present-day eastern Mali, from 1493 to 1528.

Although to be strictly accurate, it recounts the life of Askia Mohammed and some of his descendants. I was interested to learn that the events were recorded in contemporary written chronicles, so we have some sense of how the stories have changed over the centuries: the genealogies have been compressed a bit, and some historical events seem to have been conflated, but the people and events are clearly identifiable.

The subject matter fits comfortably into what you might expect of epic poetry: kings, conquest, revenge, wrangling over succession. But of course it also has cultural specifics; for example, Askia Mohammed is remembered for spreading Islam in West Africa, and one of his notable achievements was a pilgrimage to Mecca. Similarly, some of the second half of the poem is the story of Amar Zoumbani, one of Askia Mohammed’s descendants, and his ambivalent social position as the son of a king and a slave woman.

It’s enjoyable as a story — if you skip over some genealogies of the Bob begat Fred begat Kevin variety — but it doesn’t seem particularly remarkable as a piece of literature. It seems to be fairly plain, direct storytelling; there’s some interesting use of repetition for emphasis, but otherwise the way the language is used seems straightforward; with the inevitable caveat that some amount has been lost in translation. Most notably, the original switched occasionally from Songhay to a version of Soninké used as an ‘occult language’ by Songhay griots, healers and sorcerers, a language which is apparently sufficiently obscure that many lines are just marked as ‘undecipherable’. There’s also some suggestion in the introduction that Malio switched between dialects of Songhay, though I may be misunderstanding; what effect any of this code-switching might have is left unclear.

I kind of feel I should be drawing comparisons with other oral/epic poetry: Greek, Haida, Norse, or Anglo-Saxon, which is the only one I’ve actually studied. But nothing insightful is coming to mind, tbh.

Anyway. The Epic of Askia Mohammed is my book from Niger for the Read The World challenge.

* The local word in Niger is actually jeseré, apparently, but it’s the same kind of poet/storyteller/musician/historian role.

» The griot speaks is © Julien Harneis and used under a CC by-sa licence. It was taken in Guinea, but that will have to be close enough.