-

'This is clearly an illustration from some alternate Anne of Green Gables, one in which Marilla sends her away to an institution instead of keeping her, and grief renders her into a transcendental halfwit.'

Tag: books

The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters

The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters, edited by Charlotte Mosley, is a selection of letters between the various Mitford sisters, who were an extraordinary bunch. From oldest to youngest: Nancy was the novelist who wrote Love In A Cold Climate and The Pursuit of Love; Pamela was least remarkable; Diana married Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists; Unity went off to Germany and became a personal friend of Hitler; Jessica ran away from home to join a cousin fighting on the communist side in the Spanish Civil War, and became a civil rights activist and writer in America; and Deborah, the only surviving sister, is now Duchess of Devonshire and spent most of her life working to make Chatsworth House into a profitable outfit.

Among the notable names that crop up: Hitler, Goebbels, Churchill, Harold Macmillan, General de Gaulle, JFK, John Betjemen, Evelyn Waugh, The Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the Queen, the Queen Mother, Prince Charles, Princess Diana, Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Noel Coward… so there’s lots of good material there.

The main interest in the early part of the book is the Big History stuff: the Nazis and Hitler most of all. I read it trying to get some sense of what appealed to Unity and Diana about Fascism, but although there are lots of letters about Hitler, and going to rallies and so on, I never quite got a handle on it. I suspect that for Diana, it was as much because of her attraction to Oswald Mosley as any ideology, but it can’t have just been that. And Unity seems to have had an with Hitler before she met him in the way someone might have an obsession with Elvis or Princess Diana. She found out where he regularly went to eat and kept going there until she had the chance to wangle an introduction.

I suppose since half of Europe went Fascist in the thirties, there’s no need for a special explanation. The same thing appealed to them as to everyone else: whatever that was. It’s perhaps easier to look back and empathise with the appeal of communism, but still, with that too it would be interesting to know what triggered it: was there some particular conversation or book? What would be enough to make Jessica run off to Spain in pursuit of it?

As the book goes on and the sisters get older and less active, the focus narrows down from these Big Issues onto their family dynamics, which are often made rather tense by the growing interest in them and the various books and TV programmes made by themselves and others. It’s still fascinating, though.

It helps that they all write well: their letters are chatty, funny, sometimes serious, and frequently quite bitchy. Nancy had the sharpest edge, but they all had their caustic moments. I probably ought to quote something, so here’s a fairly random bit that I thought showed a sharp eye. This is Diana writing to Deborah in 1960; Max is her son. He’s the Max Mosley currently in the news, as it happens.

Yesterday Max fetched me in the Austin Healey Sprite & drove me to Oxford where Jean had made a delicious middle day dinner. The flat is marvellous, not one ugly thing, & a view over playing fields to real country & a garden with an apple tree. ALL the wedding presents were being used — your car, Desmond’s china, Emma’s Derby ware, Viv’s pressure cooker, Muv’s pink blanket on the bed and (pièce de résistance) Wife’s coffee set — also of course Freddy Bailey’s canteen of silver.

Oh Debo, the pathos of the young. Don’t let’s think.

Charlotte Mosley, who edited the book, is daughter-in-law of Diana, so one wonders if she is, or could be, completely objective — it’s impossible to know whether she has quietly laundered anything out, and apparently, even at 800 pages, what appears in the book is a tiny percentage of the total — but I thoroughly enjoyed it.

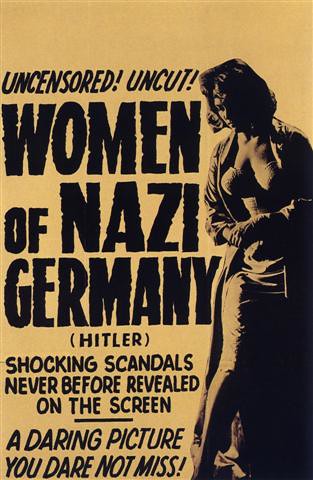

» the image, which has nothing to do with the Mitfords beyond the obvious, is POSTER – WOMEN OF NAZI GERMANY, posted to Flickr by Bristle’s Film Posters [ W1 ]. If it’s working, that is: Flickr seems a little flaky today.

Happy Bloomsday

June 16th is Bloomsday, the date that Leopold Bloom spends wandering the streets of Dublin in Ulysses.

The picture above is taken from Joyce Images, a site ‘dedicated to illustrating Ulysses using period documents’. And here’s a bit of Sirens:

Bronze by gold, Miss Douce’s head by Miss Kennedy’s head, over the crossblind of the Ormond bar heard the viceregal hoofs go by, ringing steel.

— Is that her? asked Miss Kennedy.

Miss Douce said yes, sitting with his ex, pearl grey and eau de Nil.

— Exquisite contrast, Miss Kennedy said.

When all agog Miss Douce said eagerly:

— Look at the fellow in the tall silk.

— Who? Where? gold asked more eagerly.

— In the second carriage, Miss Douce’s wet lips said, laughing in the sun. He’s looking. Mind till I see.

She darted, bronze, to the backmost corner, flattening her face against the pane in a halo of hurried breath.

Her wet lips tittered:

— He’s killed looking back.

She laughed:

— O wept! Aren’t men frightful idiots?

With sadness.

Miss Kennedy sauntered sadly from bright light, twining a loose hair behind an ear. Sauntering sadly, gold no more, she twisted twined a hair. Sadly she twined in sauntering gold hair behind a curving ear.

— It’s them has the fine times, sadly then she said.

The Invention of Tradition

The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, is a selection of essays by different historians. To quote the blurb:

Many of the traditions which we think of as ancient in their origins were, in fact, invented comparatively recently. This book explores examples of this process of invention […]

There’s a great quote in the section on the British monarchy. This is Lord Robert Cecil in 1860, after watching Queen Victoria open parliament:

Some nations have a gift for ceremonial. […] This aptitude is generally confined to the people of a southern climate and of a non-Teutonic parentage. In England the case is exactly the reverse. We can afford to be more splendid than most nations; but some malignant spell broods over all our most solemn ceremonials, and inserts into them some feature which makes them all ridiculous… Something always breaks down, somebody contrives to escape doing his part, or some bye-motive is suffered to interfere and ruin it all.

150 years later, the British have bigger, more pompous and more gilt-ridden ceremonies than almost anyone, and we see ourselves as especially good at pageantry: the opening of parliament, coronations, jubilees, royal weddings and funerals, and all of it presented as though it was ancient continuous tradition. And in fact much of the content, at least for the coronation, is ancient: it’s just that between the early 17th and late 19th centuries, the preparation was generally half-arsed and the results shambolic. Apart from anything else, the symbolism was awkward; Britain was a democracy of a sort, and as long as the monarch was a partisan political figure people were reluctant to surround them with all the trappings of divinely-provided power. It was only once the monarch was reduced to a figurehead that we could safely put them in the centre of these grand pantomimes.

The book also has an essay about the Scots (all that twaddle about clan tartans) and the Welsh (druids and the Eisteddfod), but those stories were broadly familiar, so in some ways the bits I found most interesting were about the British inventing traditions out in the Empire. For example, in India, where they had the problem of how best to assert Imperial authority over a ‘country’ which was in fact hundreds of small kingdoms held together by force, and how to project Queen Victoria as the focus of that authority while she was thousands of miles away. And although the British had been in India for a long time by then, this represented a new focus, since it was only in the wake of the Sepoy Mutiny/India’s First War of Independence in 1857 that control of India was taken from the East India Company and taken over by the state.

So in 1876 they held the ‘Imperial Assemblage’ to mark Victoria’s accession to her imperial title as ‘Kaiser-i-Hind’ when Indian kings/princes/maharajas gathered with their entourages at a site near Delhi to take turns to approach a pavilion decorated in British heraldic imagery, and each was presented with a banner which had a coat of arms in the European heraldic tradition, designed for the occasion by a Bengal civil servant called Robert Taylor. It sounds like an extraordinary event: apart from the basic weirdness of it, the scale was immense; ‘at least eighty four thousand people’ attended in one role or another. Sadly I haven’t managed to find a picture of the event, but below is the banner presented to Rajabahadur Raghunath Savant Bhonsle, the ruler of Savantvadi.

Thinking about all this reminded me of my own little moment of inventing tradition. When I was at university, there a couple of people at my halls of residence who wanted to start an all-male discussion club where the members would take turns to present a little speech on some interesting topic, and then everyone would drink sherry and discuss. A couple of friends and I took great delight in coming up with a ludicrously silly constitution for the club, which laid down arcane traditions and provided bizarre titles for the various officers. For example, every meeting was supposed to start with ‘the toasting of the Pope’: a different Pope each week, working through them in chronological order from St Peter onwards. There was no Catholic connection, pro or anti; I think it was just that the phrase ‘the toasting of the Pope’ was amusing. In the event there was one meeting and then the club fizzled out. And a good thing too, frankly.

Actually, though, the whole episode was rather fitting; after all, the University of Bristol itself is an institution whose landmark building is a vast Gothic edifice built not in the middle ages, or even at the height of the Gothic Revival in the mid C19th, but in 1915. Pretending to be older than it is — pretending to be Oxbridge, really — is what Bristol does.

Anyway, the book is interesting; some of the essays are better than others — Hobsbawm’s own contribution struck me as especially weak — but I’m glad I read it. A slight typographical gripe: irritatingly, quoted passages are marked only by the left margin being indented exactly as much as the first line of each paragraph is indented, which makes it extremely unobvious which paragraphs are quoted. I’m not suggesting that’s a reason to avoid the book; I was just irritated by it.

» img364, posted to flickr by Black and white archive, shows the 1953 Coronation celebrations in Edith Road, Smethwick. The banner is from the British Library.

Going Dutch by Lisa Jardine

Full, slightly overblown title: Going Dutch: How England Plundered Holland’s Glory. This is a book about the relationship between England and Holland in the C17th. It’s an interesting period, of course: the C17th was Holland’s ‘Golden Age’, when the country was not only a wealthy global power but at the intellectual and especially artistic forefront of Europe. For me, the art is especially remarkable: there are three of the all-time greats in Rembrandt, Rubens and Vermeer, and a huge number of other important artists like Gerrit Dou, Pieter de Hooch, Frans Hals, Jan Steen, and Aelbert Cuyp.

Indeed, not only were the Dutch producing lots of their own great artists: they exported them over the channel; most notably but not only Anthony Van Dyck and Peter Lely, who between them seem to have painted most of the society portraits in England at the time. And of course the other most notable Anglo-Dutch connection was that by the end of the century, England had acquired a Dutch king: William of Orange.

That acquisition is usually referred to by the British as ‘The Glorious Revolution’, a name which combines just the right amounts of grandeur and vagueness to discourage too much analysis. But as Jardine makes clear, seen from an outside perspective, and especially perhaps from a Dutch perspective, it looks an awful lot like the Dutch conquest of England. William sailed across the channel with a fleet of 500 ships and 40,000 men, including 20,000 armed troops, marched on London and took power. The only reason it can be remembered as anything Glorious, rather than a bloody conquest or yet another Anglo-Dutch war, is that James II didn’t put up a fight. He was unpopular with just about everyone, not least because he was Catholic, and not really getting on with his own army, and he decided to flee rather than press the issue. Who knows what would have happened if he’d been a little more forceful and decisive.

This was, in some ways, a family affair: William and his wife Mary were both grandchildren of Charles I.* In fact they probably would have been most likely to succeed James II anyway, except that James’s wife, after a long string of miscarriages, unexpectedly produced a male baby and screwed everything up for the Oranges.

The strength of William-and-Mary’s claim to the throne made it easier for the English to accept them as joint monarch; Lisa Jardine’s books sets out to demonstrate that the tangled relationship between the Stuarts and the House of Orange is actually typical of a very strong cultural link between England and Holland throughout the C17th; that much of what became typically English, and much of the groundwork that enabled England to became a great power in the C18th and C19th, came from Holland.

She certainly successfully demonstrates an enormous amount of interaction between the two countries: in art, music, gardening, science and indeed socially. One of the most striking examples was the testing of Christian Huygens’s clock design on a British ship; Huygens had been corresponding with members of the Royal Society in London, who arranged for his new clock to be tested as a possible solution to the longtitude problem by a captain in the Royal Navy. On the very mission where he was testing this Dutch clock design, the captain plundered all the Dutch trading posts along the coast of Ghana, triggering the Second Anglo-Dutch War in the process. You might think this would interfere with relations between London and the Hague, but no, the correspondence carried on as though nothing had happened.

I suppose the only question a sceptical reader might have is whether you would find similar levels of influence and connection if you studied, say, Anglo-French relations at the same time. Is there a specific and exceptional connection between England and Holland at this period, or just the normal amount for two neighbouring countries? She seems pretty convincing to me, but I’m not in a position to judge.

* I’ll try to explain, but the same names keep coming up attached to different people, so you’ll need to concentrate. Charles I’s daughter Mary married William II of Orange; her son William is the one who became king of England. He, William III of Orange, married another Mary, the daughter of James II and thus the granddaughter of Charles I (and his own first cousin). So when he invaded England, he was deposing his uncle and father-in-law.

» The pictures are all details from the wedding portrait of the fourteen-year-old William to the nine-year-old Mary, painted in London by Anthony Van Dyck and now in the Rijksmuseum. Both because that picture seems appropriate and because there’s a high-quality reproduction of it in the Wikimedia Commons.

The Mabinogion trans. Sioned Davies

I didn’t do my normal thing of looking for appropriate reading materials before going on holiday — I mean, I’d already read How Green Was My Valley and Under Milk Wood, so there didn’t seem to be much point in looking for anything else.*

But when I was running out of reading matter and went to the bookshop in St David’s, I was half-looking for something Welsh and settled on the Mabinogion. I knew the name but nothing else about it; as it turns out, it’s not one work at all; it’s a selection of medieval Welsh stories from several manuscripts. Some of them form connected groups, but it was the C19th translator Lady Charlotte Guest who put this selection of stories together and gave them their usual title.

Many of them are set in the court of King Arthur, and the most conventional seemed just like the equivalent English stories. I’m open to persuasion that, as the translator’s introduction claims, there is some kind of distinctive Welsh character to them; but I can’t bring myself to care very deeply. I tend to find all those medieval romances kind of boring.

Some of the stories are more distinctive, though, and more interesting: most notably the ‘four branches of the Mabinogi’ from which the collection takes its title. I think with most Arthurian stories, even though they feature magic and strange creatures, they operate according to a narrative logic that seems familiar to us, whether because it was in some way the ancestor of the modern novel, or because of the regular bursts of of medieval revivalism that have revisited the material. With the ‘four branches’ that doesn’t seem true: they are odder and untidier. It’s hard to explain; you might have to read them if you’re curious.

They reminded me slightly of the Haida stories translated by Robert Bringhurst, so I wonder if it’s a property of oral storytelling that we just get glimpses of in the remnants of oral culture that survive here and there in manuscript form. Partially perhaps it’s an episodic form: the story teller pulls together various episodes and mini-stories, and the emphasis is different every time, without perhaps the need to tidy it into a neat overall narrative. Or maybe there’s a kind of dynamic that’s created when you’re telling stories to people who already know them.

This is apparently a very new translation, only in the shops a week or two before I bought it. I can’t possibly assess it as a translation, since I don’t know any Welsh and haven’t read any other editions, but I found it readable and the introduction and notes were helpful, so I give it a thumbs up.

*No, not really. It just didn’t occur to me to think about it until too late, for some reason. Incidentally, How Green Was My Valley was, in a slightly cheesy way, a much better book than I was expecting. I think I ended up leaving my copy in Tokyo, though.

The picture, incidentally, is a bit of cosplay from a fan of the Korean MMORPG called Mabinogi.