The latest blockbuster exhibition at the RA is Byzantium 330-1453. It’s a big show, but then it does survey a millennium’s worth of art from a big empire.

It’s odd; I think most people who have even a general interest in history and culture have some knowledge, however sketchy or inaccurate, of classical Greece, Rome, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance. But the thousand year-history of Byzantium is somehow not part of that, and I was very aware going around this exhibition of how little I knew. It makes you think that perhaps the Great Schism of 1054, which separated Catholic and Orthodox christianity and so in some sense split Europe into east and west, is the pivotal moment in the continent’s cultural history.

[ Editorial aside: every time I start to say anything I find myself very aware of my ignorance. But even at the best of times I tend to hedge opinions around with qualifications, and for stylistic reasons there’s a limit to the amount of verbiage I can hang onto a sentence. So let me say up front: I don’t want you to think that I think I know what I’m talking about. I don’t. ]

Voltaire apparently described Byzantium as ‘A worthless repertory of declamations and miracles, a disgrace to the human mind’, and there seems to have been a general dismissal of Byzantine culture by a lot of western writers. I’m not sure the exotic and peculiar version in Yeats’s poems is actually any more flattering, either. Perhaps it’s because if you’re from the tradition that sees the Middle Ages as a regrettable regression between the classical civilisations and the Renaissance, Byzantium looks like a bit of a mistake: they started as Romans, spent a few centuries developing a medieval aesthetic and then stuck with that for the next 500 years until the Renaissance came along and moved art forward again.

Or at least, I imagine the ‘stuck in a rut’ theory is a horrible caricature, but there does seem to have been a somewhat rigid artistic culture. The exhibition leaflet explains that between 730 and 843, the Byzantines had an iconoclasm. Which firstly means, of course, that a lot of the early transitional art was destroyed.* But also, to quote the exhibition leaflet, ‘Following the failure of iconoclasm the Triumph of Orthodoxy was celebrated in pictures and with an explosion of artistic activity. … Orthodoxy was declared to be the use of icons; and icons declared the nature of Orthodoxy.’

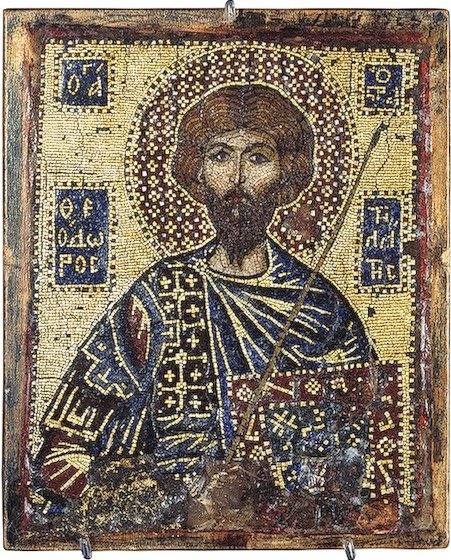

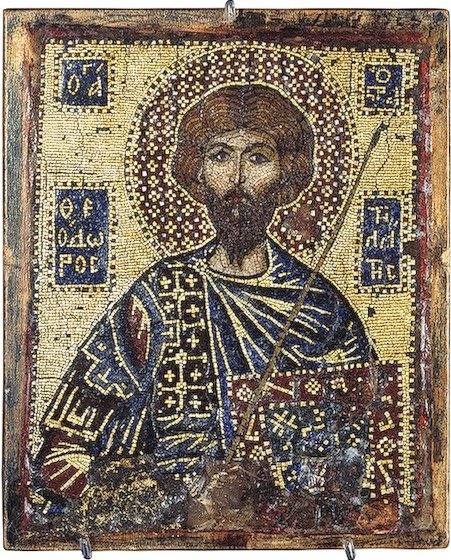

Whether it’s because of the strong identification of a artistic tradition with a religious identity, or because the icons were seen primarily as devotional objects rather than artworks, to my untrained eye they all look very similar. And indeed if you see, say, C19th Russian icons, they still all look fairly similar. It’s like statues of Lenin in the USSR: originality really wasn’t the point. In fact, when it came to statues of Lenin, originality would probably have been actively suspicious; I don’t know if the same dynamic is at play with Byzantine icons.

Anyway, getting back on to more solid ground: you should go to see this exhibition because it has lots of nice stuff in it. Icons, of course, both painted and in the slightly ridiculous medium of micromosaic; lots of carved ivory; manuscripts, featuring all sorts of attractive scripts, mainly Greek but some Arabic, some Cyrillic and some completely mysterious; chalices and other items inlaid with precious stones and fabulous little enamel designs; jewellery, coins, ceramics and textiles. The first few rooms are chronological, but other rooms are arranged by theme: ecclesiastical objects, domestic objects, icons, the interaction between Byzantium and the West, the influence of Byzantium on nearby cultures and so on. It is, as I said, a big exhibition, and a lot of the items are small, finely worked objects that really deserve close examination, which is never easy in a busy gallery; I don’t think there’s any straightforward solution to that, though.

The exhibition website isn’t very comprehensive, although there’s an education guide in PDF form which has some nice pictures.