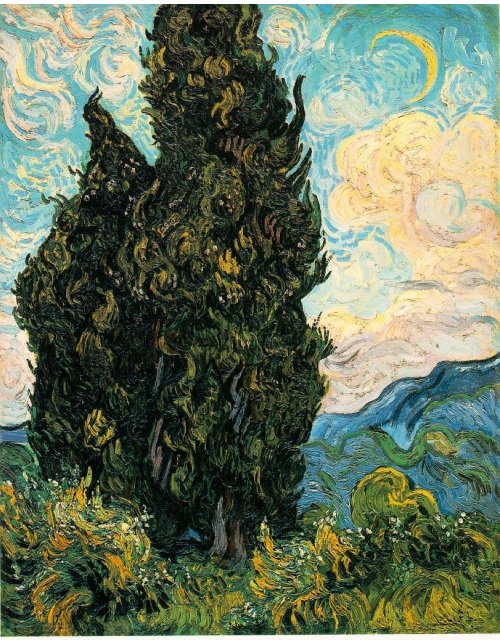

Not that rubbishy fake Van Gogh that other galleries having been fobbing us off with, then.

The exhibition’s full title is ‘The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters’. The inclusion of some of Van Gogh’s letters supposedly provides a bit of biographical-intellectual-psychological context for the paintings. Which is an interesting idea, but calling it ‘The Real Van Gogh’ is still ridiculous.

The show hardly needs a special hook to attract the public’s attention; it is, somewhat surprisingly, the first major Van Gogh exhibition in London for 40 years, and I’m quite sure that it will be packed for the whole run. And rightly so: it has a lot of marvellous paintings in it. Van Gogh is so universally popular that the bloody-minded part of me almost wants to argue that he’s overrated, but I can’t bring myself to do it. Quite apart from anything else there is to say about his work, there is just such a lot of straightforward pleasure to be had from it.

Looking at the late landscapes I found myself thinking of El Greco: the strength of colour, the tension in the distorted forms, the stretching of the possibilities of figurative painting without losing that connection with real objects. By which I mean: he doesn’t seem to have been heading towards abstraction in that way that, in Cezanne’s landscapes, the mountain sometimes seems to be fragmenting into patterns of light and colour. Van Gogh’s landscapes are full of the thingness of things.

So it is a marvellous exhibition which I highly recommend. On the other hand I thought the letters were a bit of a sideshow. Most of them were written to his brother Theo; in the relatively short sections which the curators have translated from Flemish or French, Vincent talks about what he has been doing, how his work is going, and provides little ink sketches of the paintings he has been doing. It’s quite interesting; you do get some sense of his personality, of how articulate and thoughtful he was. And some of what he has to say about the work is somewhat interesting. But even without buying into the Death Of The Author idea that the artist’s life is irrelevant to understanding the work, I do think there is a limit to its value. Artists’ comments about their own work always seem so vague and generic compared to the specificity and particularity of the work itself; which I guess is why they end up as artists rather than writers. And the awkwardness of putting too much text in an exhibition mean that you’re not getting that much of Vincent’s thought anyway.

Perhaps there is a particular value in providing this kind of biographical material for Van Gogh, since he is probably still widely thought of as the mad genius artist. The letters at least give a more rounded sense of a real human being, since he comes across in them as, well, fairly normal. Intelligent, good with languages and incomprehensibly good with paint, but certainly not frothing at the mouth. I guess that point is worth making.