The South Bank Centre is marking 70 years since the end of WW2 with a collection of events entitled Changing Britain. The Hayward Gallery’s contribution is an exhibition History Is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain.

Filtering collective history through their individual perspectives, seven British artists of different generations and backgrounds – John Akomfrah, Simon Fujiwara, Roger Hiorns, Hannah Starkey, Richard Wentworth and Jane and Louise Wilson – each curate distinct sections of the exhibition and provide their unique ‘take’ on recent British history.

As you might imagine, it’s a bit of a mixed bag. John Akomfrah has selected a whole range of films from the Arts Council Film Collection, which I pretty much skipped, because who has the patience to watch seventeen different pieces of video art in a row? I hope some people do, but not me. Roger Hiorns has put together a whole exhibition of material related to the BSE crisis, arranged chronologically, and I found it really interesting to go back and revisit that period but I’m not sure I was responding to it as art — whatever that means. The only reason it couldn’t have been an exhibition at the Science Museum is that contemporary art has a willingness to be more boring — or at least dense and text-heavy — than a traditional museum would dare.

The two I enjoyed most were Hannah Starkey and Richard Wentworth. Hannah Starkey selected 70s, 80s and 90s photography from the Arts Council Collection, which she juxtaposed with commercial photography in a somewhat heavy-handed but still effective way. So glossy ads for fashion and booze were contrasted with grimy, peeling 1980s unemployment offices and so on. I don’t know if that contrast was absolutely necessary — the photographs would have been effective on their own — but it was still good. Richard Wentworth’s was the most crowd-pleasing section. To quote the blurb: ‘Through his eclectic selection of objects, artworks and artefacts Wentworth takes us from post-war austerity to the optimism of the 1950s and into the gloom and paranoia of the Cold War.’ So there was some art by people like Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, and Henry Moore, lots of press clippings, lots of old books which were thematically appropriate but also appealing for their mid-century graphic design, various objects like a 1950s TV, and most dramatically a decommissioned anti-aircraft rocket launcher out on the balcony.

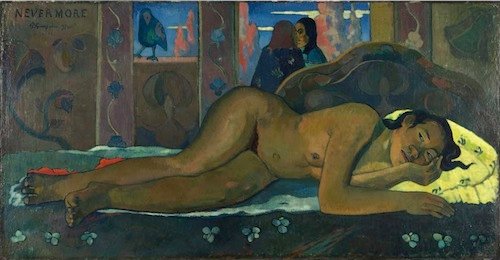

Meanwhile at Tate Modern they have Marlene Dumas: The Image as Burden. Marlene Dumas is a South African artist who paints rough, blobby paintings, nearly all of people. I enjoyed it much more than I expected because the Tate have done a terrible job of marketing it. Or at least a terrible job of marketing it to me. All the pictures I’d seen made her work look dismal and unattractive, and quite a lot of it is a bit like that: lacking immediate visual appeal (which is not the same as being bad, but doesn’t make me rush to go and see it). Particularly, there are paintings in black ink which are dark and grey and miserable looking. But actually her larger oils are much more likeable, and some of them are even quite colourful. I didn’t come out of the exhibition as her biggest fan, but I certainly liked it more than I thought I would.

And at Two Temple Place is Cotton to Gold: Extraordinary Collections of the Industrial North West. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, there were some people in Lancashire making a hell of a lot of money from cotton mills and other industry. And some of them put that money into collecting historical manuscripts, or old coins, or beetles, or Turner watercolours, or Japanese woodcuts… With the result that there are apparently some particularly notable regional museums up there. But for the moment a lot of those coins and beetles and whatnot have been lent to Two Temple Place.

It’s an enjoyable kind of exhibition to visit: the building is attractive, entry is free, and if one cabinet leaves you cold, well, the next one will have something completely different. Last year they had a similar exhibition of items from the various University of Cambridge collections; I think that one was better, with more varied and more remarkable exhibits, but Cotton to Gold is enjoyably eclectic in the same way.

» The painting is Evil is Banal, Marlene Dumas, 1984. Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands. © Marlene Dumas. Photo credit: Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands.