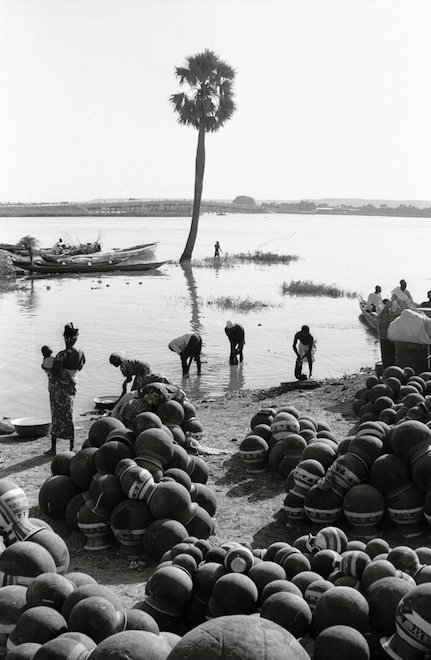

Full title: Of Water and the Spirit: Ritual, Magic and Initiation in the Life of an African Shaman. Somé was kidnapped at the age of four and taken first to a Jesuit-run boarding school and then a seminary, where he was a victim of physical and sexual abuse. At the age of 20 he fled the seminary and walked back to his home village. When he saw his family for the first time in 16 years, he could no longer speak his native Dagara and had lost touch with his native culture; so he underwent the long, harrowing ritual initiation that boys normally go through at 13.

He then realised that his calling was to go out and teach the western world about traditional wisdom; the book ends with him leaving the village again. He went to university and earned a few degrees, and he now seems to work on the New Age lecture circuit and in the men’s movement.

I have to say, as I read the introduction which explains this stuff, my heart sank. The cocktail of academic jargon, self-help, the supernatural and purple prose could have been specifically designed to annoy me. But, to be fair, once he gets going, it is pretty interesting. He never completely shakes off the tendency to flowery prose…

The sun had already risen. A few scattered clouds were speeding across the empty zenith as if running away from the threat of the burning disc.

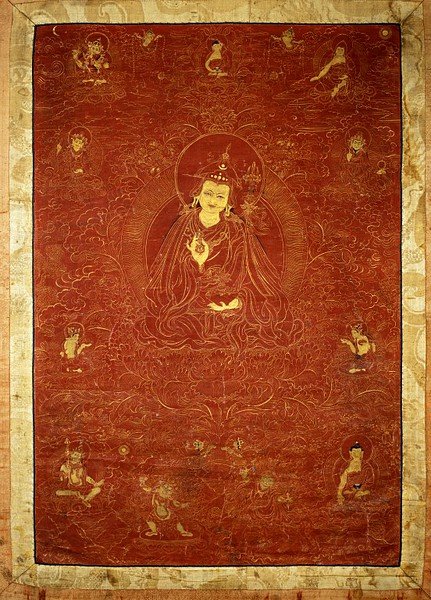

… but the academic and self-help stuff is much less intrusive. And the supernatural is after all the main subject of the book. As I was reading his descriptions of magical experiences he had before his abduction, all of which happened before he was four, I wondered whether all the impossible things he was witnessing were explicable by his extreme youth, and the embellishing powers of memory. But his experiences during the initiation as an adult are every bit as remarkable.

Assuming that he’s not just a professional bullshitter who made all this stuff up because he knows it is marketable — and I’m not really suggesting that’s the case, although it did occur to me as a possibility — his visions/experiences were extraordinarily complex, specific and precise. Since I’m not a believer in the supernatural, I couldn’t help speculating about what kinds of psychological and physiological effects might have created these experiences — quite fruitless, of course, since we only have one very specific perspective on what happened and I don’t have that kind of expertise anyway.

Really, that’s not the point, anyway; I’m not reading with the book to argue with it. What I would hope to get out of this kind of book is some kind of insight into the traditional culture of the Dagara. And there certainly is some interesting material about the rituals, about the use of divination, the decision making of the elders and so on. But the magical experiences themselves weirdly didn’t ring true to me.

I know I’m the worst person in the world to judge the authenticity of shamanic experience, but when I’ve read stories from oral cultures before I’ve always been struck by the genuine weirdness of them, a lack of the kind of narrative logic I expect. I don’t get that from this book; for all the impossible things happening, they sort of read like a version of shamanic experience as imagined by a westerner. Perhaps that’s unsurprising, given the relatively small proportion of his life Somé actually spent in his home village compared to the time spent elsewhere. He is inevitably as much a product of French colonial education and western universities as he is of Dagara culture. Or perhaps he is consciously targeting it at a western readership. Or, very likely, my idea of what a shamanic experience ought to be like is completely wrong.

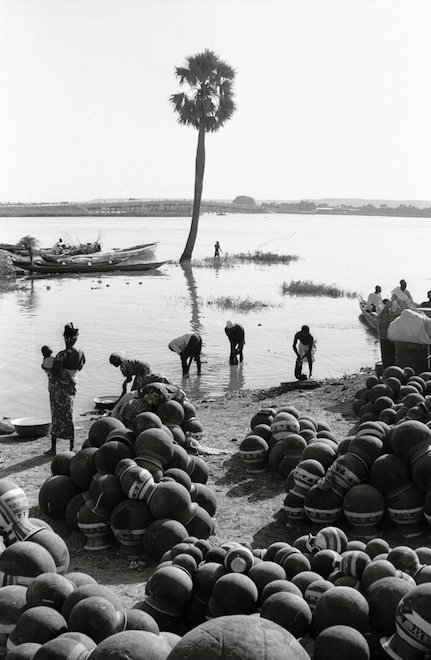

One way or another, it’s certainly interesting. Of Water and the Spirit is my book from Burkina Faso for the Read The World challenge.