Not the current debacle in Iraq, the ’39-’45 war. I’m reading the second volume of the Mass-Observation diaries (see my post about the first one here), and I thought I’d just pick out a couple of quotes. After the battle of Alamein:

The newspapers are in ecstasies. There are more maps than ever, showing arrows pointing in all directions, arrows inside arrows, arrows straight and arrows coiled and curving like snakes, and various other wonderful symbols. It is a military map-makers paradise. As Mr H said, ‘You’d think the war was over from the Daily Express headline.’

From a different diarist, this made me laugh:

A neighbour called and left us a Homeopathic tract, and a report on the analysis of some other neighbour’s urine. The latter was probably an oversight.

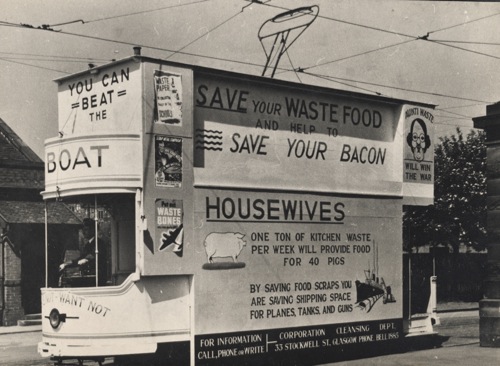

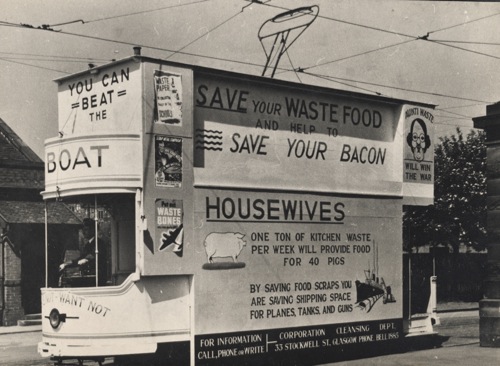

A wartime tram; picture from The Glasgow Story. You can see a bigger version on their site.

And here’s a woman who has just started work for the United States War Shipping Administration in Glasgow:

I don’t get told much in my new job. At first I thought my new boss Captain Macgowan did not intend to give away secrets till he knew me, but there are many indications that he trusts me – I have a key to the safe where all the private papers are put away. A reserved disposition is a big element, coupled, I think, with a belief that I should be upset if I knew ‘all about’ submarine attacks and the like.

The captains of American vessels have instructions to look us up on arriving and most of them like being in an American atmosphere so much that they come back again and again. They talk freely enough and I am getting to know heaps about life and sea and what seamen are like on shore.

It is a novel environment for me. A woman’s woman, an ardent feminist, a patron of cultural clubs with cups of tea and little cakes (not too plentiful nowadays) me, to be suddenly plunged into a super-masculine world. I must say that viewing them at close quarters, men are getting much better than I thought them before – by men meaning American captains.

I’ve got to the point where the worst of the war, from a British POV, is past, although the diarists don’t know that. The Russians and Americans are both now in the war on the Allied side, the threat of invasion has receded, the Germans have lost the battles of Alamein and Stalingrad. There’s a long way to go, but the Third Reich has peaked.

After the 7/7 bombings, the idea of the Blitz spirit was thrown around a lot, especially by Americans: the time when the British stood alone against the world and kept a stiff upper lip. i couldn’t help feeling, though, reading the diaries of the period, that if you were going to be anywhere in Europe during WWII, Britain was really quite a good choice. Admittedly, and it’s an important point, none of of the diarists are living in the East End of London—or Coventry, or Plymouth, or any of the hardest-hit areas—but still, there were no battles fought street-by-street across Birmingham or Ipswich, no occupation, no starvation, no concentration camps.

You still sometimes see a few left-over anti-tank fortifications if you go for country walks in Kent; if they’d ever been needed, if the Panzers had ever been rolling across Romney Marsh, the pluckiness of the British would have had a real test. The fact that some of those who name-checked the Blitz a couple of years ago were probably the same people who made cheese-eating surrender monkey jokes about the French in the build up to the Iraq war is particularly nauseating.

I guess everyone tends to see world history with themselves at the centre, though. I remember someone posting a poem at an online workshop once which referred to Ireland as having a ‘blood-soaked’ landscape. Well, I know that Ireland’s history has been pretty brutal at times, but blood-soaked compared to Russia? or France? China? Poland? Cambodia? My point being… I don’t know, really. Be wary of self-mythologising, I guess.