-

'The Elements of Style does not deserve the enormous esteem in which it is held by American college graduates. Its advice ranges from limp platitudes to inconsistent nonsense. Its enormous influence has not improved American students' grasp of English grammar; it has significantly degraded it.'

-

I didn't realise the 'Keep calm and carry on' poster was designed for the event of a successful German invasion. Adds a whole new creepy note to it.

Tag: WWII

Not the current debacle in Iraq, the ’39-’45 war. I’m reading the second volume of the Mass-Observation diaries (see my post about the first one here), and I thought I’d just pick out a couple of quotes. After the battle of Alamein:

The newspapers are in ecstasies. There are more maps than ever, showing arrows pointing in all directions, arrows inside arrows, arrows straight and arrows coiled and curving like snakes, and various other wonderful symbols. It is a military map-makers paradise. As Mr H said, ‘You’d think the war was over from the Daily Express headline.’

From a different diarist, this made me laugh:

A neighbour called and left us a Homeopathic tract, and a report on the analysis of some other neighbour’s urine. The latter was probably an oversight.

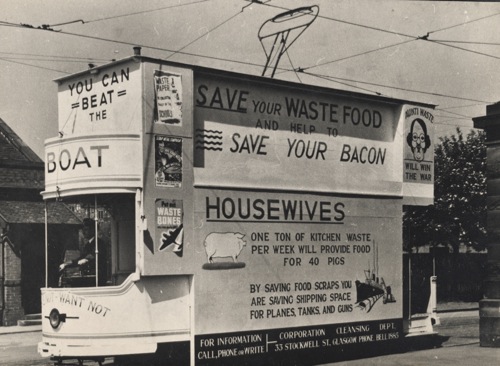

A wartime tram; picture from The Glasgow Story. You can see a bigger version on their site.

And here’s a woman who has just started work for the United States War Shipping Administration in Glasgow:

I don’t get told much in my new job. At first I thought my new boss Captain Macgowan did not intend to give away secrets till he knew me, but there are many indications that he trusts me – I have a key to the safe where all the private papers are put away. A reserved disposition is a big element, coupled, I think, with a belief that I should be upset if I knew ‘all about’ submarine attacks and the like.

The captains of American vessels have instructions to look us up on arriving and most of them like being in an American atmosphere so much that they come back again and again. They talk freely enough and I am getting to know heaps about life and sea and what seamen are like on shore.

It is a novel environment for me. A woman’s woman, an ardent feminist, a patron of cultural clubs with cups of tea and little cakes (not too plentiful nowadays) me, to be suddenly plunged into a super-masculine world. I must say that viewing them at close quarters, men are getting much better than I thought them before – by men meaning American captains.

I’ve got to the point where the worst of the war, from a British POV, is past, although the diarists don’t know that. The Russians and Americans are both now in the war on the Allied side, the threat of invasion has receded, the Germans have lost the battles of Alamein and Stalingrad. There’s a long way to go, but the Third Reich has peaked.

After the 7/7 bombings, the idea of the Blitz spirit was thrown around a lot, especially by Americans: the time when the British stood alone against the world and kept a stiff upper lip. i couldn’t help feeling, though, reading the diaries of the period, that if you were going to be anywhere in Europe during WWII, Britain was really quite a good choice. Admittedly, and it’s an important point, none of of the diarists are living in the East End of London—or Coventry, or Plymouth, or any of the hardest-hit areas—but still, there were no battles fought street-by-street across Birmingham or Ipswich, no occupation, no starvation, no concentration camps.

You still sometimes see a few left-over anti-tank fortifications if you go for country walks in Kent; if they’d ever been needed, if the Panzers had ever been rolling across Romney Marsh, the pluckiness of the British would have had a real test. The fact that some of those who name-checked the Blitz a couple of years ago were probably the same people who made cheese-eating surrender monkey jokes about the French in the build up to the Iraq war is particularly nauseating.

I guess everyone tends to see world history with themselves at the centre, though. I remember someone posting a poem at an online workshop once which referred to Ireland as having a ‘blood-soaked’ landscape. Well, I know that Ireland’s history has been pretty brutal at times, but blood-soaked compared to Russia? or France? China? Poland? Cambodia? My point being… I don’t know, really. Be wary of self-mythologising, I guess.

This is one of a trilogy of books using material from the Mass-Observation archives. To quote Wikipedia:

Mass-Observation was a United Kingdom social research organisation founded in 1937. Their work ended in the mid 1950s … Mass-Observation aimed to record everyday life in Britain through a panel of around 500 untrained volunteer observers who either maintained diaries or replied to open-ended questionnaires.

We Are At War is an account of the period from August 1939 to about the start of the Blitz, compiled from the diaries of five M-O participants. It’s a simple idea and it works brilliantly. The diaries combine the texture of everyday life—people write about the weather or what’s on the radio—with the backdrop of great events happening in Europe.

[photo from the Museum of London picture library]

People’s moods—not just the diarists, but their workmates and family—are one of the most interesting things: swings between optimism and pessimism about the war, including, in the early stages, whether it was even going to happen; the stress of expecting air raids for months before they actually start happening; endless gossip about German spies supposedly having been arrested after committing some faux pas to reveal their identity; a distrust of official news and an uneasy fascination with listening to Lord Haw-Haw.

One thing that’s noticeable is a gradual hardening of attitudes towards the Germans; initially people try to maintain some kind of distinction between the Nazis and the German people, and express some kind of regret at news of German casualties, but they get increasingly ruthless as time goes on and British casualties rise.

I could quote almost any chunk of this book; but this will do, from February 1940 in Glasgow:

Recently Miss Crawford saw a notice in a fish shop: ‘Fish cheap today.’ On looking closer she found the stock consisted of a few pieces of sole at 3s 4d. Since the war broke out I have stopped looking at the fish shops for I know the prices would be too high. It transpires that practically everyone has ceased to eat fish, but the price is not the sole cause. Miss Carswell said she could not bear to eat fish because she remembered what perils the fisherman had been through to get it. Then she continued that she could not bear to eat fish in case they had been feeding on all the dead bodies. Her mother had offered her tinned salmon. ‘for that had been canned before the war began’.

(As usual, this review has also been posted to my recently read books section.)

Crete by Antony Beevor

The story of the German invasion of Crete during WW2 and, to a lesser extent, the resistance thereafter.

This is really a book of cockups all round; the Germans had already taken the Greek mainland and planned a completely airborne invasion of Crete using paratroops and gliders which was, as it turned out, wildly ambitious, not least because a man floating down on a parachute is an easy target for someone on the ground. Moreover, thanks to Bletchley Park, the Allied commander had access to information derived directly from German radio traffic.

Nonetheless, thanks to bad planning (for example, the Allies had been in the island for many months, but they still didn’t have a robust communications network in place), lack of initiative, and most crucially, the Allied CO’s misunderstanding of the intelligence he was being given, the Germans managed to take Crete, although with enormous losses, and the Brits, Aussies and New Zealanders had to make a scrambled retreat across the island. Helped by the terrifying ferocity of the Cretans, who had several centuries of experience fighting guerrilla wars against the Ottoman Empire, and since becoming part of Greece in 1918, had kept in practice with hunting and blood-feuds.

And of course with the Allies gone, the Germans then had a brutal crack-down on the Cretans. After the invasion the British helped set up a resistance network on the island, and eventually as the tide of the war turned, Crete was won back.

The overriding thing I was left with from the book was Crete once again getting caught up in the violent arguments of big countries that really had nothing to do with them.

The book feels a bit British-centric, but other than that it seemed to give a good account of what happened, and Beevor writes well.

Colonial troops in WWII

I found this article in the Independent interesting. There’s a film coming out in France called Indigènes about “the 300,000 Arab and north African soldiers who helped to liberate France in 1944.” Apparently about half the French army in 1944 was African or Arab. The director and producer, both French of North African descent, “hope the film will remind the majority population of France that the country owes a deliberately obscured debt of blood to colonial soldiers with brown and black skins. They also hope the film will persuade young French people of African origin that they belong in France.”

In one respect, the film has already succeeded where years of complaints have failed. Last week, just before it reached the cinema, the French government was shamed into paying belated full pensions to 80,000 surviving ex-colonial soldiers who, since 1959, have been paid a fraction of what French veterans receive.

All of which is quite interesting, but I was mainly struck that the article managed to get all the way through exuding a sense of superiority to those racist French without commenting on the British parallel. There were really quite a lot of colonial troops fighting for the British in the war, most notably the Indian Army, which in WWII was the largest all-volunteer army ever assembled. Unsurprisingly, the Indian Army was important in the Burma campaign, but they also fought in North Africa, the Middle East and Italy. I think I read once that a third of troops at the battle of El-Alamein were Indian. There aren’t too many Indian faces in all those old war films, though, and I really don’t think most British people know anything about their role. And given that the Ghurkas who are current members of the British army still don’t get the same pensions as their British counterparts, it seems a fair bet that Indian veterans of El-Alamein and Monte Cassino don’t either.

This particular blindspot in the British view of history isn’t simply a race thing, of course. Only a minority of the ‘British’ Eighth Army at El-Alamein was actually British; apart from the Indians, there were troops from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and Rhodesia; and even a few Free French and Poles. But I only know that because I just looked it up in Wikipedia, and I imagine that most people in this country would have assumed, like me, that the British Army was, basically, British.

Quite apart from the fact that le fairplay demands these things be better known, the French example makes me think – there must be a good film in this somewhere. Or novel. Or even poem, at a pinch.