I downloaded this from Project Gutenberg after reading Hudson’s novel Green Mansions. The novel — a rather peculiar romance about a wild girl found living in the Venezuelan jungle — has has not aged particularly well; personally I found Birds in London much more interesting, although non-London non-birders will inevitably find it less so.

Some of it is interesting as colourful period detail; some of it simply as evidence of long term trends in bird numbers. Here’s a bit of period colour before I get onto the geekier stuff:

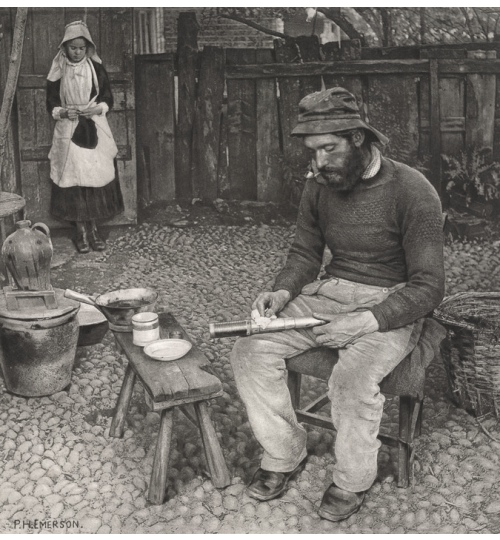

My friends, Mr. and Mrs. Mark Melford, of Fulham, are probably responsible for the existence in London of a good number of wandering solitary jackdaws. They cherish a wonderful admiration and affection towards all the members of the crow family, and have had numberless daws, jays, and pies as pets, or rather as guests, since their birds are always free to fly about the house and go and come at pleasure. But their special favourite is the daw, which they regard as far more intelligent, interesting, and companionable than any other animal, not excepting the dog. On one occasion Mr. Melford saw an advertisement of a hundred daws to be sold for trap-shooting, and to save them from so miserable a fate he at once purchased the lot and took them home. They were in a miserable half-starved condition, and to give them a better chance of survival, before freeing them he placed them in an outhouse in his garden with a wire-netting across the doorway, and there he fed and tended them until they were well and strong, and then gave them their liberty. But they did not at once take advantage of it; grown used to the place and the kindly faces of their protectors, they remained and were like tame birds about the house; but later, a few at a time, at long intervals, they went away and back to their wild independent life.

My reaction after a couple of chapters was that Hudson would be delighted by the number of birds that have returned to central London, and horrified by the number that have been lost from the surrounding countryside. And of course it’s a bit more complicated than that, but it’s broadly true. So, writing about small birds in the central parks (Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, Green Park, and St. James’s Park), Hudson says:

Even the old residents, the sedentary species once common in the central parks, find it hard to maintain their existence; they have died or are dying out. The missel-thrush, nuthatch, tree-creeper, oxeye [great tit], spotted woodpecker, and others vanished several years ago. The chaffinch was reduced to a single pair within the last few years; this pair lingered on for a year or a little over, then vanished. Last spring, 1897, a few chaffinches returned, and their welcome song was heard in Kensington Gardens until June. Not a greenfinch is to be seen, the commonest and most prolific garden bird in England, so abundant that scores, nay hundreds, may be bought any Sunday morning in the autumn at the bird-dealers’ shops in the slums of London, at about two pence per bird, or even less. The wrens a few years ago were reduced to a single pair, and had their nesting-place near the Albert Memorial; of the pair I believe one bird now remains. Two, perhaps three, pairs of hedge-sparrows inhabited Kensington Gardens during the summers of 1896 and 1897, but I do not think they succeeded in rearing any young. Nor did the one pair in St. James’s Park hatch any eggs. In 1897 a pair of spotted flycatchers bred in Kensington Gardens, and were the only representatives of the summer visitors of the passerine order in all the central parks.

The robin has been declining for several years; a decade ago its sudden little outburst of bright melody was a common autumn and winter sound in some parts of the park, and in nearly all parts of Kensington Gardens. This delightful sound became less and less each season, and unless something is done will before many years cease altogether. The blue and cole tits are also now a miserable remnant, and are restricted to the gardens, where they may be seen, four or five together, on the high elms or clinging to the pendent twigs of the birches. The blackbird and song-thrush have also fallen very low; I do not believe that there are more than two dozen of these common birds in all this area of seven hundred and fifty acres.

Nearly all of those species can now be found in those parks. Not necessarily in huge numbers, but they’re all there, even the ones which had completely disappeared at the end of the C19th.

The only exception is the spotted flycatcher, which is a species that has declined by over 70% since 1970. When I was a child, we had a pair breeding in the garden in south London; I haven’t seen one around here for many years. And that points towards the other big pattern: the loss of birds in the countryside. Obviously the book is about London, but it does cover the suburbs where London blends into the countryside; which in 1898 meant places like Hampstead, Dulwich, Clapham, and Kew.

And Hudson’s lists for those places are a depressing reminder of how much we have lost. Tree pipit, redstart, wood warbler, barn owl, red-backed shrike, wryneck, turtle dove, partridge, nightingale, grasshopper warbler, cuckoo, yellowhammer, hawfinch, marsh tit: it’s extraordinary to think that all these birds were breeding within five miles of the centre of London. Some can still be found in a few places within the M25 if you know where to look, but some, like red-backed shrike and wryneck, are effectively extinct in the UK. Others, like the turtle dove, are probably going to join them sooner rather than later.

So, against this background of general decline, why are there more birds in central London than a century ago? Hudson blames the lack of birds in Victorian London on three main things: persecution, insensitive management, and cats. One thing he doesn’t mention, incidentally, is pollution. The fact that the Thames was too dirty to support many fish must have been one reason there weren’t any herons in central London, and it seems likely that the very smoky air would cause similar problems for birds, either directly or through an impact on insect numbers. And sometimes it must be that birds adapt to a new way of life: when Hudson was writing, the woodpigeon had recently changed from being a rural species with a few pairs in the older parks to a common London species. Perhaps there was some subtle change in the habitat, but it seems more likely that there was a change in the birds’ behaviour.

Of Hudson’s three suggested causes: well, there are still lots of cats in London, although there may be fewer strays, thanks to neutering campaigns and organisations like the RSPCA and Battersea Dogs & Cats Home. And habitat management has certainly improved; local councils and the Royal Parks now see it as part of their job to encourage wildlife. Even in the past ten or fifteen years there has been a change, I think, and it’s clear walking around London parks that the traditional urge towards tidiness has been replaced by a willingness to leave areas of grass uncut, to leave dead trees in place, to allow patches of brambles and ivy. And among the public as well, there is more interest in wildlife gardening and more people putting up nestboxes and feeding the birds.

But the biggest cultural shift has been to do with human persecution. Already the passages I’ve quoted make reference to jackdaws being sold for trap shooting and wild greenfinches being sold as cage birds; the book also refers to the popularity of bird’s-nesting (i.e. egg collecting). All those things are now illegal and, perhaps more importantly, socially unacceptable. And the credit for that has to go to people like W.H. Hudson, who was a founder member of the RSPB.

A lot of birds were also simply shot. Shooting some species of bird is still legal under some circumstances, either for food or ‘pest control’, but clearly both gun control laws and environmental protections are vastly stricter than they used to be.

The other story was of a skylark that made its appearance three summers ago in a vacant piece of ground adjoining Victoria Park. The bird had perhaps escaped from a cage, and was a fine singer, and all day long it could be heard as it flew high above the houses and the park pouring out a continuous torrent of song. It attracted a good deal of attention, and all the Hackney Marsh sportsmen who possessed guns were fired with the desire to shoot it. Every Sunday morning some of them would get into the field to watch their chance to fire at the bird as it rose or returned to the ground; and this shooting went on, and the ‘feathered frenzy,’ still untouched by a pellet, soared and sung, until cold weather came, when it disappeared.

The most obvious beneficiaries have been birds of prey and crows, whose populations are still recovering from the impact of persecution and pesticide use. There were no birds of prey in Hudson’s London; even when I started birding 25 years ago, kestrels were about the only species. Since then, peregrines, buzzards and ravens have all returned to the southeast of England, and there are peregrines nesting in the centre of town. The sparrowhawk has replaced the kestrel as London’s commonest bird of prey. And thanks to a reintroduction program in the Chilterns, there is the occasional wandering red kite, raising the possibility that a bird which used to feed on the rubbish heaps of Elizabethan London might return after an absence of 235 years.*

I knew that birds of prey and ravens were recovering from very low numbers; before reading this book I didn’t fully appreciate that the same story was true of the smaller crows. Hudson spends a whole chapter on the now-common carrion crow, ‘the grandest wild bird left to us in the metropolis’, which he thinks is in danger of being lost from London, thanks partially to persecution by park-keepers who want to protect ornamental wildfowl. But even more surprising to me was this passage about magpies, which are now a very common and visible London bird:

The magpie is all but lost; at the present time there are no more than four birds inhabiting inner London, doubtless escaped from captivity, and afraid to leave the parks in which they found refuge—those islands of verdure in the midst of a sea, or desert, of houses. One bird, the survivor of a pair, has his home in St. James’s Park, and is the most interesting figure in that haunt of birds; a spirited creature, a great hater and persecutor of the carrion crows when they come. The other three consort together in Regent’s Park; once or twice they have built a nest, but failed to hatch their eggs. Probably all three are females. When, some time ago, the ‘Son of the Marshes’ wrote that the magpie had been extirpated in his own county of Surrey, and that to see it he should have to visit the London parks, he made too much of these escaped birds, which may be numbered on the fingers of one hand. Yet we know that the pie was formerly—even in this century—quite common in London. Yarrell, in his ‘British Birds,’ relates that he once saw twenty-three together in Kensington Gardens. In these gardens they bred, probably for the last time, in 1856. Nor, so far as I know, do any magpies survive in the woods and thickets on the outskirts of the metropolis, except at two spots in the south-west district.

I did actually know that magpies have spread into London relatively recently, because I have a copy of Atlas of Breeding Birds of the London Area from 1977, and it shows few breeding pairs in inner London. But the fact it had been completely extirpated from Surrey is really startling.

And while on the subject of crows, here’s a nice passage on jackdaws:

I have often thought that it was due to the presence of the daw that I was ever able to get an adequate or satisfactory idea of the beauty and grandeur of some of our finest buildings. Watching the bird in his aërial evolutions, now suspended motionless, or rising and falling, then with half-closed wings precipitating himself downwards, as if demented, through vast distances, only to mount again with an exulting cry, to soar beyond the highest tower or pinnacle, and seem at that vast height no bigger than a swift in size—watching him thus, an image of the structure over and around which he disported himself so gloriously has been formed—its vastness, stability, and perfect proportions—and has remained thereafter a vivid picture in my mind. How much would be lost to the sculptured west front of Wells Cathedral, the soaring spire of Salisbury, the noble roof and towers of York Minster and of Canterbury, if the jackdaws were not there! I know that, compared with the images I retain of many daw-haunted cathedrals and castles in the provinces, those of the cathedrals and other great buildings in London have in my mind a somewhat dim and blurred appearance. It is a pity that, before consenting to rebuild St. Paul’s Cathedral, Sir Christopher Wren did not make the perpetual maintenance of a colony of jackdaws a condition. And if he had bargained with posterity for a pair or two of peregrine falcons and kestrels, his glory at the present time would have been greater.

I couldn’t agree more. Sadly there are still no jackdaws on St Paul’s, but Hudson would be delighted to know that there are peregrines nesting on the Houses of Parliament. Which seems like a suitably upbeat point to end on; I could keep talking about this stuff for ages, but this post is quite long enough already. If you really still want more, you might as well read the book.