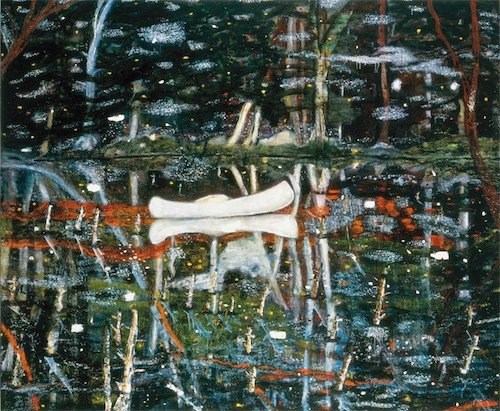

Something a bit more contemporary for a change. Today we have White Canoe, by Peter Doig:

Like so many of these paintings it loses some of the effect when you shrink it right down to 500 pixels — it’s actually eight foot wide. Nice though, innit.

Something a bit more contemporary for a change. Today we have White Canoe, by Peter Doig:

Like so many of these paintings it loses some of the effect when you shrink it right down to 500 pixels — it’s actually eight foot wide. Nice though, innit.

Ah, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, what a lot of names he had. And what a fabulous painter he was. Not in a style which is particularly fashionable these days; Neoclassical history paintings and portraits aren’t the sort of thing that would usually draw huge crowds to a London gallery.

But Ingres is brilliant enough and, I think, just odd enough to transcend fashion. He manages to make his subjects look simultaneously seductive and a bit creepy. If this woman (Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn, princesse de Broglie) turned up in an episode of Doctor Who, you would just know she wasn’t really human. Some kind of hyper-intelligent intergalactic praying mantis disguising herself via a morphobioenergy field, by the looks of her.

I saw this one at the Royal Academy’s exhibition Treasures from Budapest (it normally lives in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest). The Fall of Man by Jacob Jordaens:

I was really struck by frailty and fleshiness of the figures. Given the C17th taste for larger women, it’s not surprising that Eve doesn’t look like something from Cranach. But Adam looks positively middle-aged. In fact, even though he’s still reaching towards the apple, he looks fallen. And I think it makes for a surprisingly touching image.

In theory, the coming of abstraction opened up a world of infinite possibilities. In practice, I guess inevitably, an awful lot of artists ended up producing a lot of very samey paintings. The zeitgeist traps us all. Max Ernst is one of those who stands out; I can’t imagine any of his contemporaries producing something like this:

That’s Petrified Forest, from 1927, which is in the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo (where you can see a slightly larger version). Those textural effects were produced by what he called grattage, which is like taking a rubbing with a crayon, but you do it with paint on a palette brush. It’s one of a whole sequence of forests with suns, which in turn are one of several sets of landscapes he painted, along with the jungle paintings and those like Europe after the Rain produced using another unusual technique, decalcomania.

I love the way that they are recognisably ‘landscapes’ despite the fact that, well, they’re not. And they have a great atmosphere to them. Gloomy and introverted.

I went to the London Wetland Centre for a spot of birding today, in the hope that the very cold weather might have conjured up something a bit special… which it hadn’t particularly. But some nice things: snipe, chiffchaff, skylark. Lots of ducks: a pintail, which is a bit unusual, but also wigeon, shoveler, teal, pochard and so on. And fuck me, did it look cold, swimming around on the mostly ice-covered lake. You can see why ducks need that thick layer of delicious fat.

Bird of the day, though, was bittern. Not quite as good a view as last time I went there in the snow, in February, when there were six or seven bitterns on site and I had unbelievably good views of them, but pretty pleasing nonetheless.

So here’s the painting, Rembrandt’s Hunter with Dead Bittern.

The ‘hunter’ is of course Rembrandt. The sheer number of self-portraits he painted is extraordinary. Some very straight, others in various moods and poses: as a hunter, as a soldier, in oriental robes.

You might think he was vain except that his self-portraits seem rather less self-aggrandising than those of some other artists. If he just wanted to flatter himself, he could have picked an image — society gentleman, rakish bohemian — and stuck to it. Instead he seems to be doing something more playful and more interesting. Or maybe he just liked working alone.

And while of course I don’t endorse the hunting of bitterns, which have suffered badly because of habitat loss, this picture does have me wondering what they taste like… I guess they might be slightly fishy?

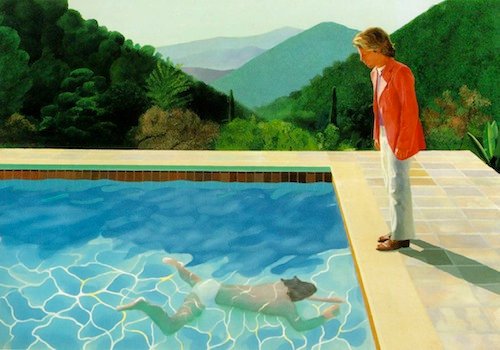

Yesterday, because it was cold and snowy, I posted a snow painting: today, because it’s cold and snowy, I’m posting a sun-drenched one. David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures).

The real thing is ten foot wide, and it doesn’t benefit from being reduced to 500 pixels; you don’t get a sense of the big flat areas of pure colour. But the composition survives, at least: the hard-edged geometrical paving against the wobbly blue of the pool, the red jacket against the dark green hills. The jacket draws your eye to the figure by the poolside, but his eyeline and the angle of the hill lead you down to the more elusive figure of the swimmer. Hockney’s paintings always seem so well balanced, they have a poised, static quality that I love.

I think you can see in his version of California the eye of a Yorkshireman; someone who doesn’t take sunshine for granted. He’s part of that whole tradition of northern Europeans who find their way south and experience all that light as a kind of miracle: Van Gogh and Matisse, heading to the Mediterranean and suddenly producing paintings full of light and colour. D.H. Lawrence, Byron, Laurie Lee.