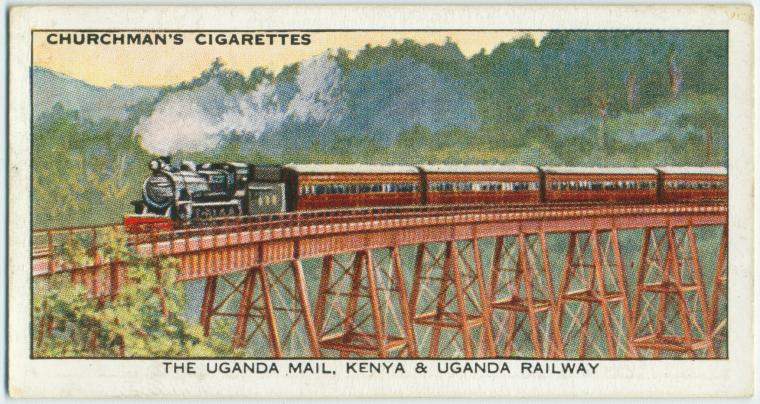

I’ve just finished Abyssinian Chronicles by Moses Isegawa. Which is a bit of a relief, because I found it quite hard work. The good stuff first: it’s a story that traces a couple of generations through the history of modern Uganda, with the arrival of Idi Amin and the collapse of his regime, the sequence of messy guerilla wars, the rise of AIDS and so on. The central character is initially brought up in a village before moving to Kampala, is from a Catholic background and is educated in a rather brutal seminary; his grandmother is a midwife; he ends up leaving Uganda to move to Holland. So there’s lots of good material. And lots of striking incidents and some strong (though not generally very likeable) characters.

Despite which, after reading a hundred pages, I checked to see how long the book was and had a sinking feeling when I saw there were still 400 pages to go.

The problem is the prose style. Quite apart from a tendency to cliché, it seems like Isegawa reacts to similes the way a small child reacts to candy. Everything is like something. These similes are sometimes quite good in themselves — he describes a priest at the seminary as having ‘an ego as large as a cirrhotic liver’ — but I found the overall effect distracting. And it’s part of a generally over-written, shouty kind of tone the book has which I just didn’t get on with; sometimes I’d get into it and be quite absorbed for twenty or thirty pages, and then some turn of phrase would snap me out of it again.

I did wonder whether it was a problem with the translation; but as far as I can tell from the title page, the book was written in English. I guess English must be the author’s second language, which is pretty impressive, but doesn’t alter the fact that I didn’t enjoy his prose.

Here’s an example of the kind of paragraph that would annoy me:

It struck him like a bolt of lightning splitting a tree down middle: Nakibuka! Had the woman not done her best to interest him in her life? Didn’t he, in his heart of hearts, desire her? Had he ever forgotten her sunny disposition, her sense of humor, the confident way she luxuriated in her femininity? The shaky roots of traditional decorum halted him with the warning that it was improper to desire his wife’s relative, but the mushroom of his pent-up desire had found a weak spot in the layers of hypocritical decency and pushed into the turbulent air of truth, risk, personal satisfaction, revenge. His throttled desire and his curbed sex drive could find a second wind, a resurrection or even eternal life in the bosom of the woman who, with her touch, had accessed his past, saved it and redeemed his virility on his wedding night. Sweat cascaded down his back, his heart palpitated and fire built up in his loins.

200 pages of this stuff would have been harmless enough, and I might have said that, despite a few flaws, it was still well worth reading; 500 pages was too much.

But I stuck it out to the end. Partially from stubbornness but mainly because I bought Abyssinian Chronicles as my book from Uganda for the Read The World challenge.

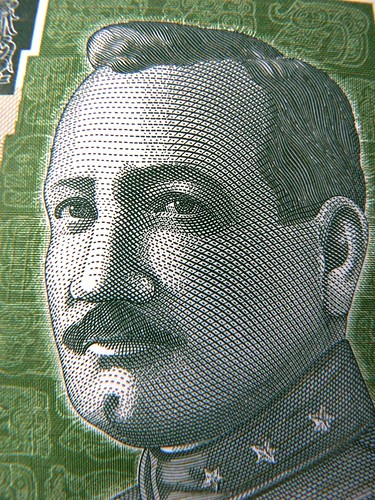

» The photo, ‘Headless‘, is © Dave Blumenkrantz and used under a CC by-nc-nd licence.