Crayford Marshes is a patch of grazing marsh on the south bank of the Thames east of London — Dartford, roughly. I heard about it as a birding spot, and a few weeks ago I went to check it out.

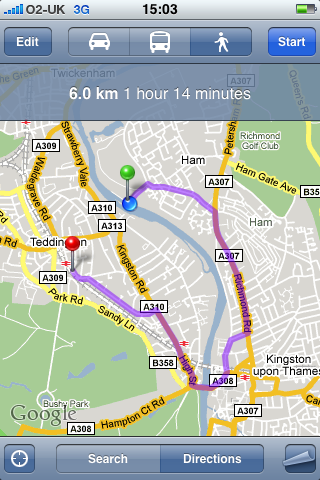

But it’s quite a small site and quite a long way away, so I decided to combine it with walking a section of the Thames Path. When I was walking the Thames path a few years ago I walked east to west, starting at the Thames Barrier at Charlton and eventually getting as far as Teddington; this time I added a section to the beginning of that walk.

Crayford Marshes itself was nice enough: it’s basically a fragment of the landscape which would once have been typical of the whole area, and which, thanks to some strict environmental protections, is still found all along much of the north Kent coast. It’s not actually a natural landscape — it’s managed for livestock and there’s a whole system of drainage ditches and embankments to keep the sea out — but it certainly feels wilder than most of the space around London, and it’s important for wildlife.

Crayford Marshes is less impressive than some of the larger areas of marshland out in Kent, but has the advantage, for birders who like to keep lists, of being in London: i.e. anything you see there can be added to your London list. It’s within the modern boundaries of Greater London, as well as the more generous London Recording Area as defined by the London Natural History Society, which is within 20 miles of St Paul’s cathedral — a somewhat arbitrary area which thankfully includes several of my favourite birding spots which would not be included in a more sensible definition of London.

I didn’t get any very spectacular birds, but I did see my first swallow and whitethroat of the year, and lots of linnets, and green sandpiper, and the lapwings were calling, which is my favourite noise in the world. And I saw little egret, which is sort of my first for London.*

Just in the middle of the marshes there’s some light industry — a scrap metal yard and some yards that looked more like distribution centres than actual manufacturing. I was just taking pictures of rusty metal textures and a man from the Environment Agency come over to say “I’m not being funny, but you want to be careful taking pictures here” and explained that the owners of the scrap metal place had been quite aggressive and accused them of taking pictures when they hadn’t even been doing it, and that they seemed to be “a bit funny about photography”.

And of course, it’s not difficult to imagine why scrap metal dealers might not want people taking pictures of their premises; particularly people from government agencies. Perhaps I’m being unfair; perhaps they were paranoid nutters rather than criminals. Either way, I took the advice and was discreet with the camera for a bit.

Once you leave the marshes and go past Erith Yacht Club, it’s a mixture of industrial stuff and housing pretty much the whole way. Among the identifiable things are the familiar piles of gravel and sand waiting, presumably, to be turned into concrete somewhere; a big sewage treatment plant, and a site generating electricity from waste incineration.

The most striking thing, for me, was that when I walked west from Charlton originally, I was walking past a similar mix of housing and industry, and I had a sense of being out on the fringes of London. This walk reminded me that I was nowhere near the edge of London that time; there is miles and miles more of that stuff stretching out along the river.

The sewage treatment plant at Crossness is on the site of one of the Victorian pumping engines installed as part of Joseph Bazalgette’s great scheme to build sewers for London. There was one pumping station on each side of the river, and Crossness was responsible for pumping all the sewage of south London into the Thames. Apparently they didn’t actually treat the sewage in those days, they just timed the release into the river to coincide with the tide going out and let the tide sweep it out to sea. Which sounds pretty horrifying by modern standards, but was a huge step up from not having a citywide sewer system at all.

It’s fitting that the Thames Path goes past the old pumping station, because in central London, a lot of the route is directly above Bazalgette’s main sewer, which runs along under the Embankment.

Also at Crossness there is a little nature reserve that gets a few decent birds, but much of it is closed to non-members. I had a quick look but didn’t see much.

Most of the way, though, what you’re walking past is miles of big, modern, self-contained housing developments. These are generally pretty ugly, which is not really a surprise if you’ve spent any time in English suburbia. There is very little evidence, looking around Britain, of the building trade putting any emphasis on beauty when building mass-market residential property. And they are probably right about the commercial logic; compared to location, facilities and price, the physical beauty of the exterior of the property must come a long way down most buyers’ priorities. But the cumulative effect is pretty deadening.

There are a couple of bits of variety: the old Woolwich Arsenal has been converted into a rather more upmarket area of housing and offices, and at Woolwich itself, you at least go near a real town centre. It’s a pretty dismal town centre, but at least there’s some sign of the variety of human life, instead of the endless ranks of apartment blocks.

Incidentally, although the Thames Path represents an admirable modern effort to create a shared public space, it doesn’t aways feel very welcoming and communitarian. You spend a lot of your time walking along next to coils of razor wire, or outside eight foot concrete walls topped with downward-pointing spikes. It seems appropriate when you’re passing commercial properties, but it does feel hostile when you’re going past residential estates — although I appreciate that families don’t want their stuff nicked either.

The Thames Path was sent on a temporary detour at the end, so I didn’t actually get to walk along the river to the Thames Barrier where I started the first time. Which was a pity.

Anyway, you can see more photos from my day on Flickr, and pictures from the rest of the route as well. The other blog posts about the Thames Path are here.

* ‘sort of’ because, from memory, it’s my first in Greater London but not my first in the London Recording Area.