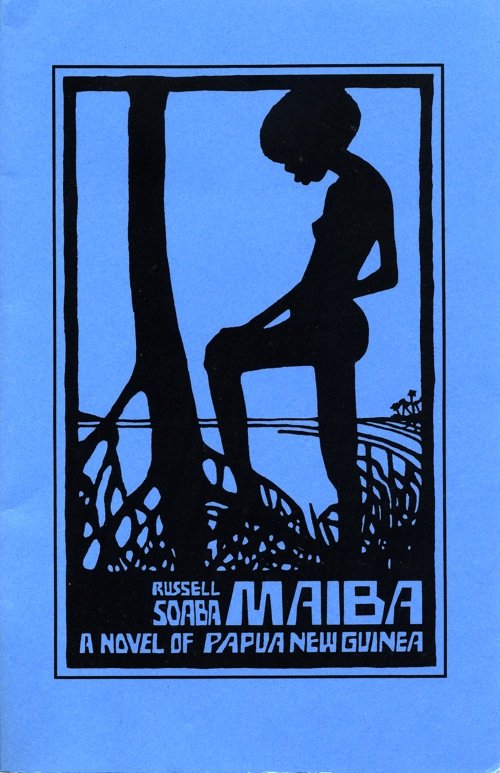

Maiba: A Novel of Papua New Guinea* is, you won’t be surprised to hear, my book from PNG for the Read The World challenge. I ordered it second-hand and was surprised to find when it came that it was a print-on-demand edition (I’m sure it’s a second-hand copy rather than one printed for me, btw). Of course POD services — or indeed e-books — are perfect for this kind of niche literature. Because of the challenge, I’ve been browsing around for second-hand copies of obscure books from around the world, and they don’t normally come cheap.

The print quality, for the moment, is noticeably weaker; my Maiba is perfectly adequate but a bit cheaper-looking and more generic than a normal mass-market paperback. But if POD helps keep books available at reasonable prices, then a slight compromise on print quality seems a good trade-off.

I imagine that most of the people ordering copies of Maiba are teaching or studying post-colonial literature, and it does fit fairly neatly into that niche. If I had to identify a central theme I’d say it was about the conflict between traditional Papuan culture and modernity — or change, anyway. The agents of change aren’t actually particularly strongly present in the book; the action takes place in a somewhat remote coastal village where the lifestyle is still fairly traditional (as far as I can judge from my complete lack of knowledge), but the relevance and authority of that tradition is oozing away.

I imagine that tradition vs. change is going to be a frequently recurring theme in the course of this challenge; but then I suppose rapid societal change has been the experience of most of the world’s population for the past century or so. Perhaps it’s just more obvious to me when I’m reading a novel set in PNG than one set in Surrey.

To be honest, I’m not quite sure what to make of it, as a novel. It’s short — only 115 pages — and rather open-ended. But it is well-suited to literary tourism; it has plenty of local detail about landscape, food, local buildings, bits of folklore and custom. And it’s well written. Perhaps my only real problem with it is that I’m not a big fan of short forms of fiction.

* Or at least that’s the title on the cover; inside it’s called Maiba: A Papuan Novel.