-

A great slideshow of beach gymnastics photos from 1930s Sydney. Via Metafilter.

Year: 2008

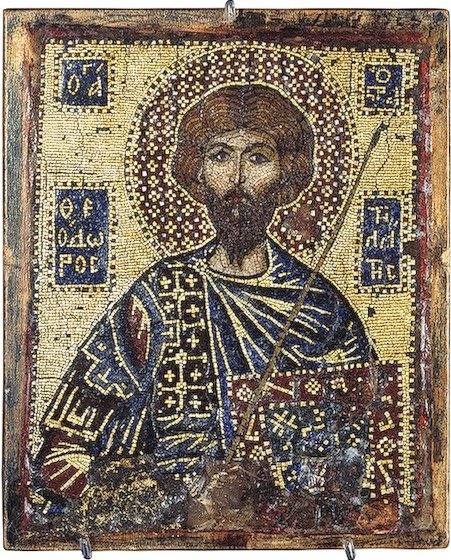

‘Byzantium 330-1453’ at the Royal Academy

The latest blockbuster exhibition at the RA is Byzantium 330-1453. It’s a big show, but then it does survey a millennium’s worth of art from a big empire.

It’s odd; I think most people who have even a general interest in history and culture have some knowledge, however sketchy or inaccurate, of classical Greece, Rome, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance. But the thousand year-history of Byzantium is somehow not part of that, and I was very aware going around this exhibition of how little I knew. It makes you think that perhaps the Great Schism of 1054, which separated Catholic and Orthodox christianity and so in some sense split Europe into east and west, is the pivotal moment in the continent’s cultural history.

[ Editorial aside: every time I start to say anything I find myself very aware of my ignorance. But even at the best of times I tend to hedge opinions around with qualifications, and for stylistic reasons there’s a limit to the amount of verbiage I can hang onto a sentence. So let me say up front: I don’t want you to think that I think I know what I’m talking about. I don’t. ]

Voltaire apparently described Byzantium as ‘A worthless repertory of declamations and miracles, a disgrace to the human mind’, and there seems to have been a general dismissal of Byzantine culture by a lot of western writers. I’m not sure the exotic and peculiar version in Yeats’s poems is actually any more flattering, either. Perhaps it’s because if you’re from the tradition that sees the Middle Ages as a regrettable regression between the classical civilisations and the Renaissance, Byzantium looks like a bit of a mistake: they started as Romans, spent a few centuries developing a medieval aesthetic and then stuck with that for the next 500 years until the Renaissance came along and moved art forward again.

Or at least, I imagine the ‘stuck in a rut’ theory is a horrible caricature, but there does seem to have been a somewhat rigid artistic culture. The exhibition leaflet explains that between 730 and 843, the Byzantines had an iconoclasm. Which firstly means, of course, that a lot of the early transitional art was destroyed.* But also, to quote the exhibition leaflet, ‘Following the failure of iconoclasm the Triumph of Orthodoxy was celebrated in pictures and with an explosion of artistic activity. … Orthodoxy was declared to be the use of icons; and icons declared the nature of Orthodoxy.’

Whether it’s because of the strong identification of a artistic tradition with a religious identity, or because the icons were seen primarily as devotional objects rather than artworks, to my untrained eye they all look very similar. And indeed if you see, say, C19th Russian icons, they still all look fairly similar. It’s like statues of Lenin in the USSR: originality really wasn’t the point. In fact, when it came to statues of Lenin, originality would probably have been actively suspicious; I don’t know if the same dynamic is at play with Byzantine icons.

Anyway, getting back on to more solid ground: you should go to see this exhibition because it has lots of nice stuff in it. Icons, of course, both painted and in the slightly ridiculous medium of micromosaic; lots of carved ivory; manuscripts, featuring all sorts of attractive scripts, mainly Greek but some Arabic, some Cyrillic and some completely mysterious; chalices and other items inlaid with precious stones and fabulous little enamel designs; jewellery, coins, ceramics and textiles. The first few rooms are chronological, but other rooms are arranged by theme: ecclesiastical objects, domestic objects, icons, the interaction between Byzantium and the West, the influence of Byzantium on nearby cultures and so on. It is, as I said, a big exhibition, and a lot of the items are small, finely worked objects that really deserve close examination, which is never easy in a busy gallery; I don’t think there’s any straightforward solution to that, though.

The exhibition website isn’t very comprehensive, although there’s an education guide in PDF form which has some nice pictures.

* incidentally, there’s a lot of discussion around at the moment of science vs. religion, and whether science is compatible with religion; meanwhile defenders of religion point to the great works of devotional art from the Hagia Sophia and El Greco to Bach. It’s worth pointing out that art and religion haven’t always had the easiest relationship either, which is why so many English churches are the proud owners of statues that have head their heads knocked off.

» the picture is taken from the website of the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, although the work, a tiny 9 × 7.4 cm C14th icon of St Theodore Stratilates in mosaic, is in the RA exhibition.

Links

-

C17th cross-sections of plants

Africa Reading Challenge: finished!

It just occurred to me that I’ve now read six books from or about Africa since I learnt about the Africa Reading Challenge. Links to the reviews:

- An African in Greenland by Tété-Michel Kpomassie

- Told by Starlight in Chad by Joseph Brahim Seid

- Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote by Ahmadou Kourouma

- The Wah-Wah Diaries by Richard E. Grant

- Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

- We killed Mangy-Dog by Luis Bernardo Honwana

I think Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote is probably my favourite out of those, but they’re all worth a look for one reason or another.

Links

-

'If his advocates didn't keep praising him as "a public intellectual" I wouldn't be rude enough to point it out, but Charles Windsor is a strikingly stupid man. Every time he has been put into a competitive situation where he is judged according to objective criteria, he has been a disaster.'

An African in Greenland is an autobiographical book; as a teenager in Togo, Tété-Michel Kpomassie read a book about Greenland and decided to go there. It took him eight years, working a variety of jobs, to make his way up through West Africa and Europe before eventually arranging a trip to Greenland, where he stayed for about two years (in, if I’ve got my sums right, 1965).

The book’s title implies that there is some kind of different perspective that Kpomassie is going to bring because he’s African, and I have to admit that it was part of the appeal for me when I bought the book. It’s such an immediately striking juxtaposition, this young man from Togo living among the Inuit and eating seal blubber: just the title is like a pitch for a cheesy Hollywood comedy.

In fact, it’s not obvious that his Africanness makes that much difference to the book, after the first couple of chapters that take place in Africa, and in retrospect it’s hard to say what I was expecting, really. There are a couple of occasions where he compares local beliefs (about the travels of the human soul in dreams, for example) with those he grew up with; and his Africanness does make him an instant celebrity in Greenland: the first black person most of them had seen, and several inches taller than most of the locals.

It is, though, an interesting and enjoyable book about Greenland: ice-fishing and dog-sledding and eating of revolting-sounding bits of raw viscera and lumps of animal fat. Whale lung! Boiled sea gull! Yummy. And as with Halldór Laxness in Iceland, endless cups of coffee.

Although actually, I think it’s to his credit that he clearly made a point of eating everything that was put in front of him, and doesn’t spend a lot of time in the book dwelling on the off-putting nature of the food. Perhaps it’s nicer than it sounds; perhaps he just wanted to downplay the potential freak-show aspect of this kind of travel book. He has a fairly clear-eyed view of the harshness of life for many of the people he meets and the social problems he encounters, but he doesn’t dwell on it excessively. Perhaps even more surprising for someone who had travelled for eight years to get there to fulfil a childhood dream, he doesn’t romanticise the country either: not too much of the noble savage stuff.

Here’s a longish passage about life during the time of the midnight sun, with 24 hour daylight:

The oddest thing was that we couldn’t get to sleep any more. To fill in the time I stayed at the school, where I took notes, sometimes until three in the morning. Kield Pedersen, the Danish headmaster, kindly gave me access to the Medelelser of his establishment — many bulky volumes which contained the findings of every piece of research done in Greenland since the days of Hans Egede.

Outside, small orange or red tents sprang up, erected by children whom the endless daylight kept from sleeping. At three in the morning you could still see them playing outside. Sometimes they went on like this for two whole days without going to bed. Eventually they dropped with fatigue, and then might sleep for two days at a stretch. It was the teachers, not the parents, who complained, because most of the time their classes were half empty.

Sleep eluded the adults, too. Everyone was restless. They had hardly set foot indoors before they were longing to go out again, to tramp on and on, to run from hill to hill. They rambled around incessantly, in search of who knows what. All through the spring they’d go wandering like this, building cooking fires in the mountains with three stones for an oven, gathering parnet berries, resting no matter where when tiredness overtook them. both with humans and animals, spring here was the season of tireless frenzies of love. Groups of boys and girls ran laughing and shouting until early morning, and there was the noise of rutting huskies fighting, the deep growls of the males mingling with the bitches’ piercing yelps. The birds sang and the eiders quacked in the creeks.

The landscape seemed excluded from this general harmony, and it changed from day to day. All the filth of Christianshåb was suddenly exposed by the sun’s return and the thaw. Snow melted n the slopes, the street became a river of mud, and innumerable streams riddled the ash-grey earth and brought to light piles of of old bottles and cans, dog shit, household waste, and rotten potatoes. All the garbage which cold and snow had preserved — now swollen with melted water, rotting fast and buzzing with clouds of flies, real flies, come out to haunt us like a bad conscience. Outside the doors and under the foundations, the houses were repulsively filthy. the borrowed coat of spotless white had covered so much offal! A sickening stench hung everywhere. the dogs, some of them now moulting, slunk squalidly about the village. You really wondered whether you were still living in the same land that had once been so clean and white.

An African in Greenland is my book from Togo for the Read The World challenge. Oh, I nearly forgot: it was translated from the French by James Kirkup.

» The photo, Oqaatsut/Rodebay, Greenland, is © kaet44 and used under a CC attribution licence. Rodebay is one of the villages where Kpomassie spent a winter in Greenland.