-

How the nice people at 4chan hacked the TIME 100 poll. "The first letters of the top 21 finalists in the poll spell out ‘Marblecake, also the game’."

Your Inner Fish by Neil Shubin

Your Inner Fish is a book which uses comparisons between human anatomy and the anatomy of other animals, living or extinct, to show how evolution helps explain the way we are and the way our bodies develop. Shubin is the palaeontologist who discovered Tiktaalik, one of the key fossils in understanding the fish/tetrapod transition, so that features somewhat, but he also draws on a wide range of examples from other species.

So for example, he traces the evolution of fin into hand over evolutionary history, but also examines how the growing embryo creates a hand (or a fin) from a blob of undifferentiated cells. He uses the evolutionary relationship between the structure of the human head and the gill arches of a shark to explain why the nerves of the head have such a peculiar relationship, how hiccuping is related to our amphibian ancestry, and so on.

Most of this material is rather technical and many of the examples were somewhat familiar to me, so the book could easily have been either impenetrable or just dull. In fact I found it worked very well; even when I had encountered some of the examples before, having them all put together into one book was very helpful. I really did feel after reading it that I was more in touch with my inner fish (and inner wormy thing, for that matter).

And it’s well written, as well. There was a rather clumsy bit in one the first chapter where he attempts to explain cladistics via a visit to the zoo, which had me worried that the book was going to be aimed at eleven-year-olds, but fortunately it turned out to be a blip. Generally the book seems well-pitched for intelligent adults who are curious about biology.

The swine flu outbreak had me thinking: presumably the very nature of infectious diseases means that, if you want to beat them, you have to act fast and take large-scale measures. You have to act, every time, as though this one is The Big One because if it is, then time is of the essence.

But of course it means the authorities are open to accusations of needless alarmism and crying wolf. This is the third ‘pandemic’ this decade, after SARS and bird flu; how many times can we have these alerts before people stop taking them seriously?

Although as long as governments keep taking them seriously, perhaps it would be no bad thing if the media treated them more as routine news stories and less like the first horseman of the apocalypse had just appeared.

I’m assuming, btw, that the swine flu is not going to be the pandemic that kills us all. I hope I’m not tempting fate.

» The photo is ‘Padrecito Posero’, © Eneas De Troya and used under a CC attribution licence.

Links

-

Even after everything we've learnt about MJ, this stuff is stranger than I would have believed. via @serafinowicz on Twitter

Watchmen by Alan Moore

Or strictly speaking, since it’s a graphic novel: words by Alan Moore, pictures by Dave Gibbons. but I think in this case it’s the writing which makes the book interesting.

I was curious to read Watchmen because after the movie came out I read and heard various people make quite grand claims for its importance. Just to pick one, one of the blurbs on this copy points out that it was ‘one of Time Magazine’s 100 best English-language novels since 1923’. And another blurb quotes ‘Lost co-creator Damon Lindelof’ as saying it is ‘the greatest piece of popular fiction ever produced’.*

I like the fact that it’s firmly within the comic-book tradition in style and subject matter; it is an attempt to make a superhero comic which is a serious work of art. Whether or not you think it succeeds, I think that’s a more interesting project than something like Persepolis, which is the presentation of an obviously worthy, serious subject in a cartoon format.

I did enjoy it; overall it works and I can see why it has a following. If I’m judging it by the standards of the great novels of the C20th, though… maybe not. I think the best thing about it is probably the characterisation. Only one of the heroes actually has superpowers; the rest are just vigilantes, and I think Moore does a good job of creating a bunch of characters who seem neurotic and broken enough to dress in spandex and go and beat up criminals. Some of the psychological explanations of why they are like that seem a bit facile, mind you. And I like some of the political themes that run through it; the fact, for example, that the heroes are generally reactionary defenders of the status quo.

On the other hand, some of the dialogue seemed a bit clunky. And when it really reached for Big Themes, especially at the end, it lost me rather. It seemed like the kind of thing that would be, like, really profound after several spliffs.

So, you know, I did like it, but I didn’t think it was one of the great novels of our time. It’s possible I’m letting my biases show.

* Time was started in 1923, which is the reason for that arbitrary cut-off; the Lindelof quote is also kind of intriguing, though, because I have no idea what he counts as popular fiction: presumably it includes Stephen King and Zane Grey, but does it include Tolkien? Dickens?

Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is an autobiography about growing up in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe. It’s about growing up in a war — Fuller was only eleven at the time of independence — and about the last throes of white colonialism and a dying way of life.

Her parents had been living in Kenya, but after Mau Mau they moved to Rhodesia, where Ian Douglas Smith had declared that there would never be majority rule, and fought to keep at least one part of Africa under white rule. Then after Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, and their farm was taken by the new government, they moved first to Malawi and then to Zambia. It reminded me of travelling in Zimbabwe nearly twenty years ago, and meeting these white people from South Africa and Zimbabwe and Zambia who seemed to have a shared identity as white Africans that had no real connection with national borders. It’s not just whites in Africa who often have an ethnic identity which doesn’t fully coincide with their nationality, of course.

You don’t have to have any sympathy with the ideal of white rule in Africa to find something melancholy in a story of people being left stranded by the tide of history, their way of life disappearing around them, and this is rather a sad book; as well as the war and the politics, the family suffer more personal losses, with several children dying young and the mother turning more and more to alcohol. But there’s a lot of humour and colour along with the gloom.

She writes well. She has a good ear for dialogue, an eye for the absurd, and her portrayal of her parents’ attitudes to race (and indeed her own childhood attitudes) is unsparing but nuanced. She doesn’t whitewash anything but she’s not interested in demonising her family either.

Here’s a little fairly randomly chosen extract:

We stop at the SPCA in Umtali and collect a host of huge dogs, and then we collect dogs abandoned by civil-war fleeing farmers. These dogs are found tied to trees or staring hopefully down flat driveways, waiting for their nonreturning owners. their owners have gone in the middle of the night to South Africa, Australia, Canada, England. We call it the chicken run. Or we say they gapped it. But they gapped it without their pets.

One day Dad says to Mum, ‘Either I go, or some of those bloody dogs have to go.’

‘But they don’t have anywhere to go.’Dad is in a rage. He aims a kick at a cluster of dogs, who cheerfully return his gesture with jump-up licking let’s-playfulness.

Mum says, ‘See? How sweet.’

‘I mean it, Nicola.’So the dogs stay with us until untimely death does them part.

The life expectancy of a dog on our farm is not great. The dogs are killed by baboons, wild pigs, snakes, wire snares and each other. A few eat the poison blocks left out in the barns for rats. Or they eat cow shit on which dip for killing ticks has splattered and they dissolve in frothy-mouthed fits. They get tick fever and their hearts fail from the heat. More dogs come to take the place of those whose graves are wept-upon humps in the fields below the house.

We buy a 1967 mineproofed Land Rover, complete with siren, and call her Lucy. Lucy, for Luck.

‘Why do we have the bee-ba?’

‘To scare terrorists.’But Mum and Dad don’t use the siren except to announce their arrival at parties.

I read Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight as my book from Zimbabwe for the Read the World challenge. As it turns out, although Alexandra Fuller’s parents spent pretty much their whole lives in Africa and she was conceived in Rhodesia, she was born during about the only two year period when they were living in England… but I’m going to count it anyway.

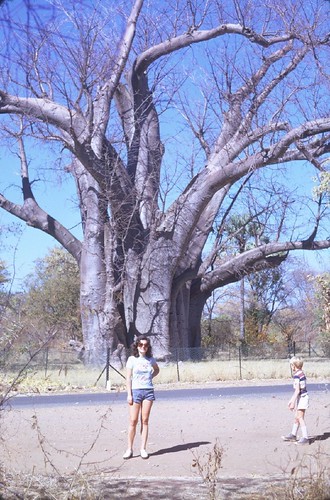

» The photo, ‘Ritsa and Baobab Tree, Rhodesia, 1973‘, has no direct connection to the book, except that it’s a picture I found on Flickr taken in the 70s in Rhodesia. It is © Robert Wallace and used under a CC by-nc-nd licence.