I always thought the US Declaration of Independence had a lovely bit of intellectual sleight of hand. It’s phrased almost as an exercise in logical deduction (various bits bolded for emphasis):

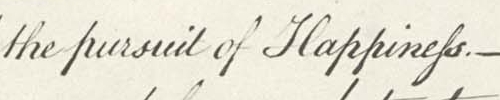

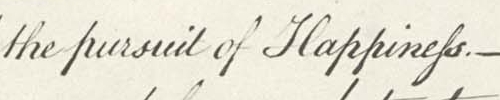

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government … [rhubarb rhubarb] … The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

[long list of ‘facts’ snipped here]

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States….

Quite apart from the awkwardness of reconciling this document with slavery, the phrase I’d particularly pick out is ‘self-evident’. Jefferson, of all people, must have known perfectly well that over the course of history, it has certainly not been felt to be self-evident that all men are created equal. Or indeed that they are endowed with inalienable rights; or that governments are instituted to secure those rights; or that they derive their powers from the consent of the governed; or that when a government fails in that respect, that it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it.

From Plato to George III, there were an awful lot of people who would have disputed those ideas; it is clearly begging the question to treat them as axiomatic.

As it happens, history has been kind to Jefferson: his revolution went well, and the country he and his cronies set up has become the most powerful on earth. The victory of the democratic way of thinking has been so thorough that it is possible to read the Declaration of Independence and take it at face value, as though it actually was a statement of self-evident truth instead of a piece of political rhetoric. Perhaps that’s for the best: if you believe, as I certainly do, that the principles laid out in the preamble to the declaration are a Good Thing, then it probably helps to have people treat them as an item of faith. But my pedantic soul revolts against it. I’m with Jeremy Bentham on this one:

Natural rights is simple nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense — nonsense upon stilts.

Those rights — life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, free speech, freedom of religion, fair trials, take your pick — are not given to us by the universe; they are human constructs, things people have chosen and demanded for themselves. All the more reason to defend them.

You may be wondering why I’ve suddenly started going on about C18th political philosophy: well, it’s because I was struck by same process going on right now with gay marriage. There is an attempt by supporters of gay marriage to frame the question as one of simple natural justice: that this is a straightforward case of equal rights* and that the answer is, in fact, self-evident.

Now I’m a supporter of gay marriage, because I think that, all else being equal, we should avoid excluding a large chunk of the population from a social institution which has a central role in the culture; because the evidence generally suggests that having people in committed, long-term relationships is a societal good, and surely having a load of people keen to marry strengthens marriage rather than weakening it; and because it just seems like a way of making people happier with no obvious downside. But any claim that it is obviously a simple question of fairness seems a bit disingenuous.

I mean: has their ever been any society anywhere which has granted full legal marriage rights to homosexual couples on exactly the same basis as heterosexual marriage? I’m no anthropologist, and there may be examples I just don’t know about, but it seems fair to say that most people through history have not thought it was obvious that homosexual relationships are the same thing as heterosexual ones. The people who argue that ‘marriage is defined as between a man and a woman’ have a point: the introduction of gay marriage does redefine marriage in a fairly major way. There’s nothing unique about that; marriage has naturally been redefined over time as society has changed. But if you’re introducing a social change which is almost unprecedented in the whole of human history, it’s hard to deny that it’s a radical agenda.

I’m not suggesting that supporters of gay marriage should present it as a radical agenda; not if they want to get it into law. On the contrary, I think they are exactly right to frame it as a question of equal rights, and tap into the American rhetorical tradition that goes back via the civil rights movement all the way to Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence. But like the Declaration of Independence, there’s a hint of a rhetorical rabbit being pulled out of a hat, as a rather controversial and radical conclusion is presented as though it was a self-evident truth.