There’s loads of good stuff in the NYPL digital gallery. I don’t really know any more about this lady except that she’s La Sylphe.

More after the jump.

There’s loads of good stuff in the NYPL digital gallery. I don’t really know any more about this lady except that she’s La Sylphe.

More after the jump.

I went to the Rothko exhibition at Tate Modern today. The show is of his ‘late series’: the centrepiece is the Seagram Murals (i.e. the group of dark Rothkos which have been in the Tate for years, plus some related works that normally live in Japan), but there are also some other groups of works (the ‘Black-Form’, ‘Brown and Grey’ and ‘Black on Gray’ paintings) as well as related odds and ends.

It’s quite suggestive, I think, that the Seagram murals were commissioned for the Four Seasons restaurant in the new Seagram building in New York, and that they ‘never reached their original destination, after Rothko decided that a private dining room was an unsuitable environment to experience his paintings.’ Because with these big colour-field paintings there is always going to be a delicate path to tread between art and interior design. And indeed you can see why the restaurant might have wanted them: they would have added a touch of modernity and sophistication without actually challenging the air of hushed pomposity which is so important to an expensive restaurant.

But although they could serve as interior design, they are certainly more than that. They are seductive pieces, and they do reward patient contemplation. Partially that’s because they are much more carefully made than the simplest description of them might suggest: a painting may be, in the most reductive terms, a big maroon blob on a red background, but they have more presence than that. Apparently he painted them with many many layers of very thin paint, and they remind me slightly of fine Japanese lacquer; the way a plain red and black rice bowl can be a deeply desirable object because of the texture and way the light falls on it.

And despite what I said in my last post, and despite the funereal colour-schemes, they aren’t gloomy. They are whatever the antithesis of frivolous is — suolovirf — but half an hour spent in their company was restful rather than depressing. They are beautiful things: big, but subtle in their colours and textures.

Or at least the Seagram murals are; some of the others were less exciting, most notably the ‘Black on Gray’ works, all divided into an area of black at the top and pale grey below. Those ones managed to be exactly as boring as the description suggests.

» The painting is ‘Red on Maroon Mural’, from the Tate. I’ve taken it from the exhibition website, which as usual with the Tate, is very good, so do go and take a look.

Dry Store Room No. 1: The Secret Life of the Natural History Museum is about the behind-the-scenes work at the Natural History Museum in London. Whether you find that an appealing subject for a book depends, I suppose, on your feelings about museums and/or natural history; personally I found it irresistible.

The public face of the museum — animatronic dinosaurs and overexcited schoolchildren — gives relatively little sense of the scientific work that goes on behind the scenes, all of which is centred on the museum’s collection of biological specimens: pressed plants, trays of pinned beetles, drawers full of bird skins or fossils, jars of starfish in alcohol. The sheer scale of these collections is hard to comprehend: the museum holds over 70 million specimens. That means every person in the UK could be given one to take home and they’d still have enough left over for everyone in Sweden. 28 million of them are insects.

The collections haven’t been accumulated simply through an excess of acquisitiveness, although there must be some connection between the satisfaction biologists get from collecting beetles and other people’s collections of stamps, obscure soul 45s or golf memorabilia. The point of the collection is that it is a vast reference library: if you find an earwig in Burma and you’re not sure whether it’s a new species, you can start by checking the literature; but if all else fails, the last resort is to go to a museum, open up the drawers full of earwigs, and start peering at them through a microscope.

This kind of taxonomical work — preparing specimens, describing species, working out their relationships, publishing highly technical articles about it — might seem to be complete drudgery to an outsider; it is slow, careful, precise, unglamorous. But it obviously has a hold on people, because the book is full of people who spend decades working on some particular group of organisms, retire, and then keep coming in to the museum to continue their work in retirement. Fortey himself is apparently one of them, retired in 2006 but still working away at his trilobites.

The books combines a history of the museum, examples of the work done there, anecdotes about characters on the staff (not surprisingly, perhaps, there have been a few notable eccentrics) and a passionate defence of taxonomy as a valuable field of study. It’s well-written, entertaining, pitched at the interested amateur, and I thoroughly enjoyed it.

» The pictures, from the Bombus pages at the NHM website, are of male bumblebee genitalia. This isn’t a highly specialised branch of pornography; it’s a normal way of identifying them (and quite a few other kinds of insects).

Today I went to the BM’s exhibition about famous wall-builder Hadrian. Its not just the wall, though; he also built the Pantheon, as well as a staggering villa complex at Tivoli. He inherited the Roman Empire from Trajan when it was at its biggest and actually reduced its size slightly, abandoning some of the less manageable extremities and consolidating the borders. In fact, topically enough, on gaining power he quickly made the decision to withdraw the troops from Iraq.

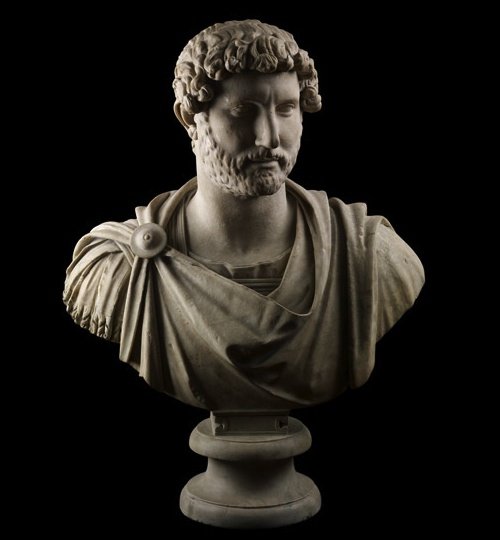

I enjoyed the exhibition (pricey, though: £12 seems a lot to me), although the Romans make for pretty familiar subject matter: portrait busts, marble columns and memorial inscriptions. And in the specific case of Hadrian, I’ve been to the Pantheon and the villa at Tivoli, and I’ve read Marguerite Yourcenar’s novel, Memoirs of Hadrian, so this wasn’t one of those exhibitions which completely opened my eyes to a new subject. Still, the quality of objects on display was high, and I learnt a few interesting snippets along the way, like the fact that Hadrian had a distinctive crease in his earlobe, visible on the portrait busts, which is an indicator of heart disease.

I suppose the other thing that’s most famous about Hadrian is the fact that when his (male) lover Antinous drowned in the Nile, he founded a city named after him, Antinopolis, and encouraged the cult of Antinous which treated Antinous as a deity associated in some way with Osiris, the Egyptian god who was in charge of flooding the Nile. The homosexual relationship itself was apparently not unusual, but the very public grief and memorialising of it was. Because of the cult, there are many surviving statues of Antinous, and they have some fabulous examples in the exhibition.

The section about Antinous mentioned in passing that in Egypt at the time, the cult of Antinous was ‘in competition with Christianity’, which made me wonder how different the world would be if he’d been more popular than Jesus.

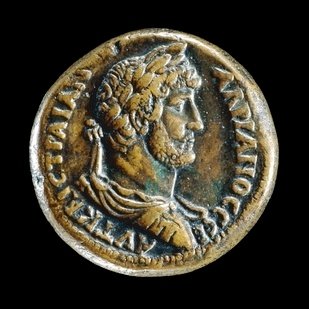

» The exhibition website doesn’t have much in the way of pictures (though there are some videos, which I haven’t looked at), but all these photos are part of the BM’s permanent collection, and are taken from their website. The coin showing Hadrian’s head is from Alexandria; the busts are Hadrian and Antinous.

As of close of play today, Great Britain is third on the Olympic medal table. It’s like, it gives you a warm glow, innit.

» The advert for Olympic Cycles of Wolverhampton is from the Evanion Collection of Ephemera at the British Library.

Radical Light: Italy’s Divisionist Painters 1891-1910, to give the exhibition its full title. Divisionism is a style of painting where the image is built up of lots of individual brushstrokes of pure colour which, ideally, merge together for the viewer but create a more luminous effect than if the colours were blended on the palette.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because it’s Pointillism under a different name. Apparently the Divisionists had heard about Pointillism and were inspired by it but hadn’t actually seen the paintings; they generally use long thin brushstrokes rather than the little dabs favoured by Seurat, but the principle is the same. Divisionism was also apprently an important stepping stone towards Futurism, the rather more famous Italian art movement.

I didn’t have very high expectations — I think obscure artistic movements are often obscure for a reason, I don’t like Seurat that much, and it got a bad review in Time Out — but, perhaps because of that, I enjoyed it. Some of the symbolist and political stuff had aged badly, but there were some really very likeable landscapes. Since the optical effect which is the whole point of Divisionism is destroyed by reproducing them as little jpegs, the pictures on the website don’t do them justice, but hey-ho.

» The picture above, taken from the exhibition website, is Angelo Morbelli’s ‘In the Rice Fields’, 1898-1901, © the owner