This Yemeni novel, in what I assume is a coincidental parallel to Orwell, was written in 1984 but set in 1948; it’s about a boy who has been taken hostage by the Imam to ensure his father’s political obedience and is sent to work as a duwaydar in the Governor’s palace. A duwaydar was a personal servant, a pre-pubescent boy who filled the role that would once have been given to a eunuch: being able to work in the women’s areas of the palace without any risk to their chastity.

However, the women of the palace do in fact seek out the boys in search of sexual gratification; this is a novel about loss of innocence, about people who are trapped (the women as well as the hostage), about a somewhat toxic intersection of emotional, sexual and power relationships. It is also, I think, a political novel in its portrayal of the Imams’ rule as decadent and arbitrary. And in the background political events are rumbling, although they only appear as echoes within the tightly circumscribed world of the novel.

I find it quite difficult to pick passages to quote for these posts — something which more or less stands alone and gives some idea of what the book is like. But anyway. Here, our hero has just smoked his first cigarette.

It left me floating in a daze, and all I could remember next morning was that my friend hadn’t stayed therewith me, because two women, neither of them Zahra, had taken him and sat on the palace steps, kissing him and squeezing further pleasures out of him. When he came back, I remember, he slammed the door violently behind him, then sank down to sleep more deeply than I’d ever seen him sleep before.

How difficult it was to wake up in this city, so different from the fortress in the mountains, with its fresh, invigorating air! In the city, you always seemed to wake with the feeling that you’d been beaten black and blue, with your body swollen like a drum or the stump of a palm tree and your eyes drooping. From the very beginning there was a lingering feeling of nausea and depression, and you didn’t usually feel the least desire for breakfast or coffee. All you wanted was cool water, and that was only to be found, if at all, in the soldiers’ jugs.

The Hostage is my book from Yemen for the Read The World challenge.

» Note on the author’s name: there doesn’t seem to be a consensus on how to transcribe Arabic words, and I’ve seen it written in various different ways [Zayd or Zaid, Muttee, Mutee or Muti]. Zayd Mutee‘ Dammaj is the spelling used in this edition; the author’s page in the Library of Congress catalogue is under Zayd Muṭīʻ Dammāj.

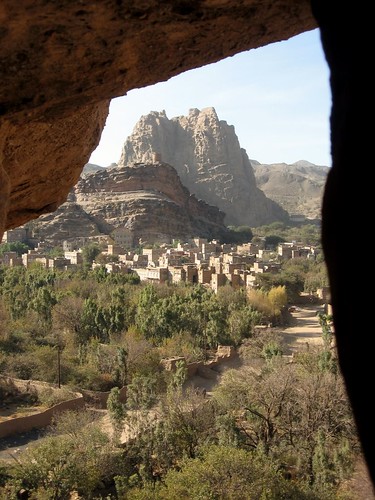

The picture is ‘the view of the village from a vindow of the Imam’s palace in Wadi Dhar’ and is © Franco Pecchio but used under a CC attribution licence.