Born in Tibet is the story of Chögyam Trungpa’s early life in Tibet, as told to Esmé Cramer Roberts. He was a year old when some monks turned up and announced he was the eleventh Trungpa Tulku and hence the supreme abbot of the Surmang monasteries in eastern Tibet; at twenty he managed to escape the Chinese occupation and make his way to India.

So the book really has three main subjects: his traditional religious education, the increasing impact of the Chinese on Tibetan life, and the adventure/survival story of escaping cross-country into India. The escape is remarkable, since it involves dozens of people trying to secretly cross some of the most difficult terrain in the world; but the portrayal of traditional life in a Tibetan monastery is what interested me most.

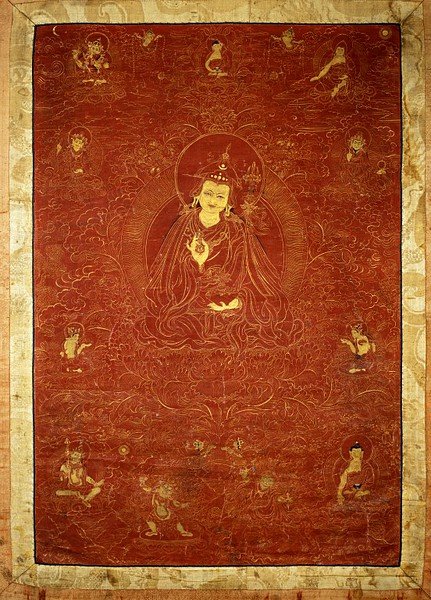

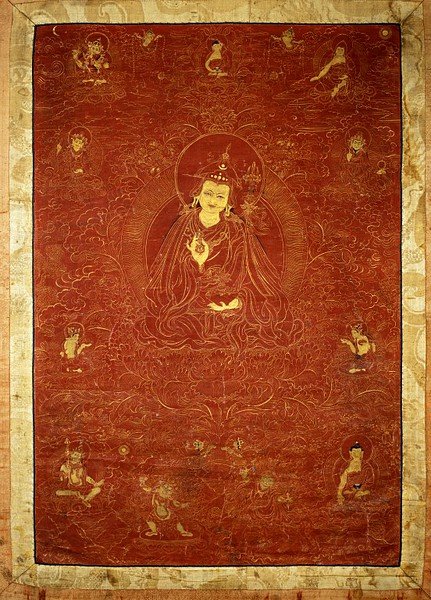

It is slightly ironic that many westerners treat Buddhism as a kind of antidote to organised religion, because this was organised, institutional religion on the grand scale: an elaborate formal hierarchy, large, expensively appointed buildings with hundreds of people, elaborate rituals, explicitly supernatural practices like divination, all supported by large scale land ownership and tributes offered by the local population. It’s rather how I imagine the middle ages in Europe must have been: a basically peasant population loomed over both by the houses of feudal aristocrats and by the abbeys and monasteries of the great religious orders.

The fact that comparison sounds like a criticism says something about the glowing image of Tibetan buddhism — mainly I guess down to the personal qualities of the current Dalai Lama — and the bad image of medieval Catholicism. The reasons for which are more tangled, although the largely Protestant history of the English speaking world is clearly relevant. Personally I have a soft spot for medieval monasticism; and my scepticism about human nature means I bet there were a few Tibetan monks over the centuries who were, let’s say, more worldly than they should have been.

Though it has to be said that Chögyam Trungpa was not living the life of a Medici pope. His life in Tibet seems to have been austerely lived and completely devoted to spiritual practice. The childhood in particular sounds tough; being taken away to a monastery at three and spending pretty much all his time from then on in study and devotion.

Anyway, it is fascinating stuff.

Our travelling party was organized with a good deal of pomp. There were thirty monks on horseback and eighty mules to carry the baggage. I was still only twelve and, being so young, I was not expected to preach long sermons; mostly I had to perform rites, read the scriptures aloud, and impart blessings. We started from the highlands and traveled down to the cultivated land; I was able to see how all these different people lived as we passed through many changes of scenery. Of course I did not see the villagers quite as they were in their everyday lives, for wherever we went all was in festival, everyone was excited and looking forward to the special religious services, so that we had little time for rest. I missed the routine of my early life, but found it all very exciting.

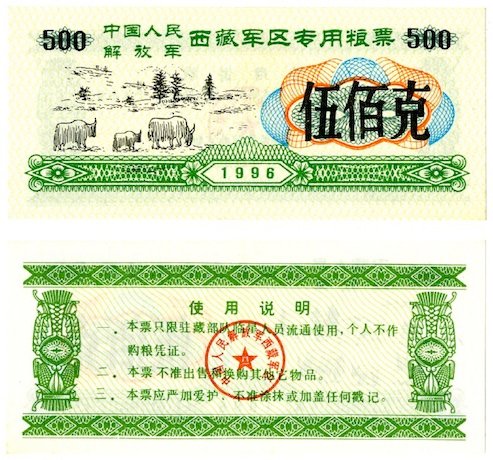

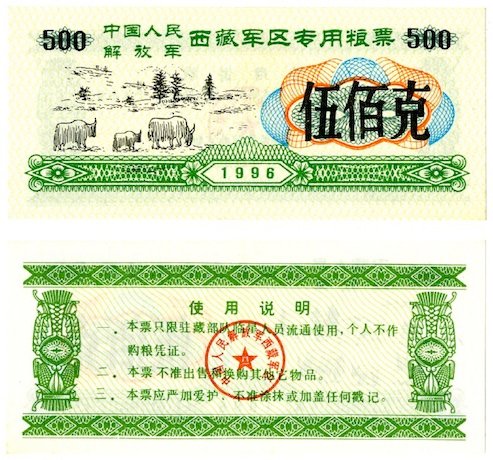

When we visited Lhathog, the king had to follow the established tradition by asking us to perform the religious rites according to ancient custom. We were lodged in one of the palaces, from where we could look down on a school that the Chinese had recently established. A Communist flag hung at the gate, and when it was lowered in the evenings the children had to sing the Communist national anthem. Lessons were given in both Chinese and Tibetan, including much indoctrination about the benefits China was bringing to Tibet. Singing and dancing were encouraged and I felt that it was a sign of the times that the monastery drum was used to teach the children to march. Being young myself I was keenly interested, though this distortion worried me; a religious instrument should not have been used for a secular purpose, nor for mere amusement. A detachment of Chinese officials sent from their main headquarters at Chamdo lived in the king’s palace together with a Tibetan interpreter, while various teachers had been brought to Lhathog to organize the school, which was one of many that the Chinese were setting up in all the chief places in Tibet. The local people’s reactions were very unfavourable. In the town the Communists had stuck posters or painted slogans everywhere, even on the walls of the monastery; they consisted of phrases like ‘We come to help you’ and ‘The liberation army is always at the people’s service.’

Born in Tibet is my book from Tibet for the Read The World challenge. Chögyam Trungpa wasn’t actually born in what is now the Tibet Autonomous Region; when the Chinese took over Tibet, large chunks which were culturally Tibetan were assigned to different provinces.

We ourselves always considered that the people who speak Tibetan and ate roasted barley (tsampa) as their staple food are Tibetans.

Which is good enough for me.