It is census time in the UK, which includes a question about your religion. So I ticked the box for ‘no religion’; but my father ticked the one for ‘Christian’, despite the fact that he is certainly not a member of any church, doesn’t go to church except for weddings, funerals and the occasional carol service, and is not, as far as I can tell, a believer.

But, you know, he went to a Christian school, and he was even confirmed into the Church of England (by the archbishop of Canterbury, as it happens). Which suggests there was a period in his life when he regarded himself as Christian. So I guess it makes sense if he regards himself as culturally Christian — whatever that means.

And I do see the value of religions as cultural identities — I can see why Jewish atheists might still want to affirm their Jewishness and maintain the rituals. Or as I’m told people used to ask in Northern Ireland, ‘but are you a Protestant atheist or a Catholic atheist?’

But as for me… I’m culturally more Christian than I am, say, Hindu — what religious education I had was mainly Christian in its focus, and I certainly know more about the culture and theology of Christianity than other religions. And at Christmas we have a tree, and presents, and a roast turkey. But those are just part of the ambient culture of Britain. Doctor Who plays a bigger part in my Christmas than Jesus. I’ve never thought of myself as Christian, so I don’t think of myself as a lapsed Christian, or a Christian atheist — if anything I’m a lapsed agnostic, since agnosticism seemed to be the fallback position amongst my peer group as a child.

The census can’t deal with such nuances, of course. Which is a pity, because that’s the kind of thing that seems interesting. We know that, because of people like my father, the census always significantly overstates the religiosity of the population:

When asked the census question ‘What is your religion?’, 61% of people in England and Wales ticked a religious box (53.48% Christian and 7.22% other) while 39% ticked ‘No religion’.

But when asked ‘Are you religious?’ only 29% of the same people said ‘Yes’ while 65% said ‘No’, meaning over half of those whom the census would count as having a religion said they were not religious.

Even more revealingly, less than half (48%) of those who ticked ‘Christian’ said they believed that Jesus Christ was a real person who died and came back to life and was the son of God.

The devoutly religious and the firmly atheist are straightforward enough; I’m curious about the shades of grey, the people who say their religion is Christian but that they are not religious. Are they mainly people who were brought up religious but don’t go to church any more? Are they defining themselves as Christian as a way of emphasising that they’re not Jewish or Muslim or whatever? Is it a generational thing? Do their children identify themselves as Christian? Perhaps ‘non-religious Christian’ can be a self-sustaining identity in its own right, comparable to secular Jewishness.

And the other side of that question is the people who tick ‘no religion’: are they mainly people who believe there is no god, or think there is no god, or can’t decide? Or are they just as likely to be people who have some kind of belief system of their own — something which they don’t think of as a religion but is not really non-belief either?

Anyway. I seem to have wandered off whatever point it was I was originally planning to make. Never mind.

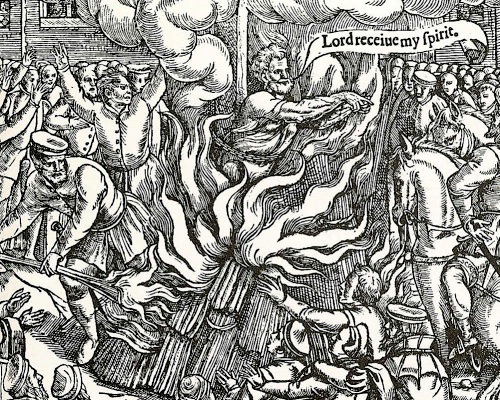

» Ruins of Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire, by John Sell Cotman.