I’m working up to writing a long post about the book I just finished, but in the meantime, here’s a quietly hypnotic video of someone hand-feeding hummingbirds:

Category: Nature

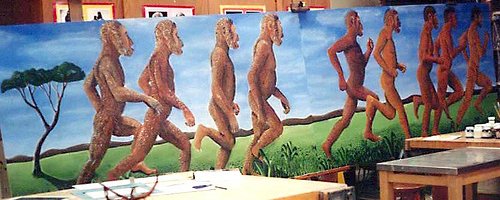

Full title: 40 Days and 40 Nights: Darwin, Intelligent Design, God, OxyContin®, and Other Oddities on Trial in Pennsylvania. In other words, it’s about the trial in Dover, Pennsylvania where the school board tried to put Intelligent Design into the biology classes and were found to be in breach of the constitutional separation of church and state.

I’m not quite sure why I felt the need to read a second book about this; the blurbs promised a more entertaining read, and it’s certainly livelier and bitchier than Monkey Girl, but didn’t tell me anything new. And despite what Hollywood would have you believe, trials are not inherently charged with drama. Especially this trial, which, with eleven plaintiffs and a bucketload of lawyers and expert witnesses, lacked a personal dramatic focus.

Chapman largely concentrates on personality and anecdote and glides past a lot of the technical evidence; understandably, I guess, but I would have liked more to get my teeth into.

» The photo above, which I found rather unexpectedly on Flickr, is of a mural painted by a student at Dover High School which helped kick off the whole controversy when one of the school board took offence at it and took it on himself to take it away one weekend and burn it. It’s used under a by-nc-sa CC licence.

At Pharyngula, P.Z. Myers comments on the Jake Young article I linked to earlier. The bit of his post I would pick out is this:

Once again, science is a method. It’s a general set of procedures that rest on skepticism, induction, empiricism, and naturalism. Atheism is a conclusion. We look at the universe using the tools of science, and it does not fit any description of the universe derived from religious perspectives: we therefore reject religious dogma. We also see that the nature of the universe does not reflect any of the orthodox conceptions of what a god-ruled universe would look like. We arrive at the conclusion that there is no god.

Science=method. Atheism=conclusion. They’re different.

I have a lot of sympathy with this argument, but with substantial reservations.

I agree with the argument this far: if you assembled a team of neutral observers to take a scientific approach to the question of the existence of God, looking at all the evidence and considering different hypotheses to explain it, I think they would reject the God hypothesis. Absence of evidence is not proof, but it certainly leaves you with a very weak case.

But still… I’m uncomfortable with saying that atheism is the conclusion reached by the scientific method. I guess the reason is this. When someone says ‘Science tells us [something]’, they are claiming a certain kind of authority for that idea. That authority has been painstakingly acquired over a couple of centuries via the slow, methodical, rigorous accumulation of data and the testing of ideas. It comes from millions of man-hours spent observing nature, collecting and classifying specimens, and devising and implementing experiments.

So a statement like ‘humans are descended from apes’ can be backed up carefully and in detail on the basis of the fossil record, comparative physiology and genetics. There are, presumably, thousands of peer-reviewed scientific papers discussing the idea. One could make similarly scientific statements about the chemical composition of tears, the weight of the electron, and thousands of other subjects.

‘There is no God’ is not, it seems to me, a scientific statement in the same way as ‘humans are descended from apes’. Most scientists may believe it to be true, and may believe that it is the conclusion most consistent with a scientific view of the world, but that doesn’t mean that it is a product of science.

The public authority of science—the willingness of people to accept what scientists say—is already probably less than it was a few decades ago, having been attacked by a peculiar combination of the religious, New Agers, alternative medicine and cultural relativists. But it is still high. What scientists say carries weight. That authority should be valued, and not invoked lightly. When a professional scientist like P.Z. Myers says that atheism is the result of science, it seems to me he is claiming that cultural authority inappropriately, and risks weakening it.

Myers rightly makes fun of the proponents of Intelligent Design for pretending to be doing science when they’re not, and frequently points out their complete lack of published scientific papers. He rightly sees that they are trying to appear to be scientific in part because they are trying to take some of the cultural authority of science for themselves. They know that if they can convince people they are scientific they will be taken more seriously. But it seems to me that he risks doing the same thing: invoking spurious authority.

There’s a post over at Pure Pedantry about the dangers of presenting science and atheism as equivalent or too closely connected; suggesting, for example, that atheism is the natural or inevitable end result of a scientific mindset.

It’s understandable that they sometimes get run together. There is a connection; it’s not a coincidence that scientists are disproportionately likely to be atheists. And because the atheist of the moment, Richard Dawkins, is a biologist by training, much of the coverage of his book and the ensuing controversy has framed it as an argument between science and religion, even though very little of The God Delusion is about science.

I really think this is a mistake, though. And I really think it would be unwise for scientists and atheists to encourage it. Partially this is for the strategic reasons that Jake Young gets into in the post I linked to above: if you link science and atheism, it is likely to make religious believers more suspicious and hostile towards science. It will also make people who for whatever reason dislike science—or are just bored by it—less receptive to atheism. Even if you are keen to promote both science and atheism, blurring the two ideas together is probably counterproductive.

But it’s not just a marketing issue. I’m keen to treat the ideas separately because I actually think they are separate. I’m not making the argument that science and religion are inherently different kinds of idea which operate in parallel (Stephen J. Gould’s ‘Non-Overlapping Magisteria’), because I think that’s a cop-out; a way of ducking the question.

No, it’s that, with the glaring exception of Genesis, I can’t see any conflict between science and scripture. Or much connection at all, really. Scientists are obviously going to be sceptical at stories like Christ turning water into wine, but as it happened (or didn’t) two thousand years ago, it’s not really open to testing. Science can point out that’s it’s impossible to turn water into wine or walk on water, but that’s beside the point; everyone knows it’s impossible. That’s why it’s a miracle. Scientists may find the idea awkward, but if a God who works miracles does exist, science will just have to live with it.

When a religion does make a scientifically testable claim—that prayer can help recovery from illness, perhaps—by all means test it, and if, necessary, challenge it. The big one, in this context, is the claim that God made the Earth in seven days. As long as there are a significant number of people who believe in the literal truth of Genesis (or any other pre-scientific creation myth), there is a real and substantial conflict of ideas between science and religion, and I would expect biologists and geologists to argue their case accordingly. And if someone comes forward today who says he can turn water into wine and walk on water (or bend spoons with the power of his mind), then test his claims.

But most of the time, that doesn’t apply. The subjects don’t generally overlap. A mathematical model for the internal structure of the proton is no more in conflict with the sermon on the mount than Aristotle’s idea of catharsis is in conflict with a recipe for fairy cakes.

Of course there is a natural tension between science and religion. The scientific emphasis on scepticism, logic and measurable evidence sits uneasily with ideas of revelation, faith and subjective religious experience. Religion’s apparent view of humanity at the centre of creation sits uneasily with the idea of evolution as a contingent, undirected process. As an atheist with an interest in science, I find the two things complementary, but they are not equivalent or inseparable.

And the main arguments against God are not scientific arguments. They may be in a similar intellectual tradition, but they certainly aren’t the result of scientific research or scientific knowledge; I imagine they had been thoroughly argued over well before most of modern science existed. The broad-brush arguments are philosophical, and the arguments against details of scripture are mainly drawn from history, archaeology, textual criticism, comparative theology and so on. Science, by providing enormous explanatory power without reference to religion, may have weakened the authority of religion, but largely without directly contradicting it (with, again, the glaring exception of Genesis).

If I was trying to convert someone to atheism, I can’t think I’d even invoke science at all. Assuming they weren’t a creationist, it just wouldn’t seem relevant.

Well, it amused *me*.

There’s a species of moth called a Lettuce Shark.

That is all.

International Rock Flipping Day

Well, I had a go at International Rock Flipping Day, flipping over various convenient rocks and bits of paving in the garden. I had a bit of a bad photography day—haven’t quite got the feel for my new camera, maybe—so the only picture worth sharing is this big fat leopard slug:

I did also see lots of ants, a centipede, a few snails, a big spider and lots of earthworms, but you’ll have to take my word for it. Oh, and woodlice.