The Kite Runner was really the obvious choice from Afghanistan for the Read The World challenge, since my mother had a copy already. I have to admit I was sceptical about it; the very fact it became so popular at a time when Afghanistan was in the news made me wonder whether its success was based more on topicality than merit. Also the UK edition has a very wishy-washy cover with a sepia-tinged photograph of a small boy on it, and while covers are often misleading, they do at least tell you something about what the publishers think is the market for the book.

And so I rather expected The Kite Runner to be a bit like the book I read for Iran, also written by a refugee who has lived for many years away their home country: nostalgic and rather insubstantial. In fact, it is much darker than I was expecting.

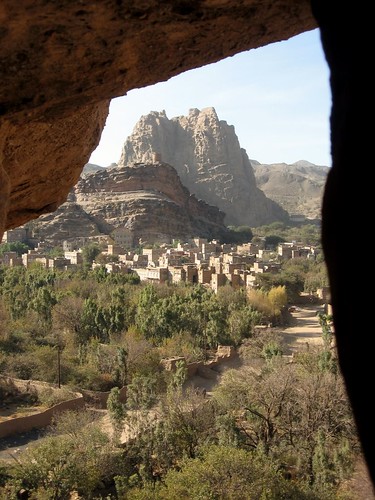

It tells the story of the narrator Amir’s childhood in Kabul, particularly focussing on his relationship with his father and his friendship with the servant boy Hassan; then his life with his father as a refugee in California in the 80s after the Soviet invasion, and a trip back to Taliban-controlled Afghanistan to do a favour for someone. Some of the darkness comes from the brutality of the past 30 years of Afghan history, but Amir’s personal story is one of betrayal and guilt even in his childhood in the relatively peaceful pre-Soviet days.

Generally I thought it was successful: the childhood stuff is gripping and moving; the portrayal of the refugee experience, and the contrast with their life in Afghanistan, is very effective; and the vision of an absolutely shattered Afghanistan under the Taliban is also pretty good. I found the book to be a genuine page-turner; I was reading until 2am a couple of times. Just to be clear, I don’t think it’s a literary masterpiece. But it is a well-written novel that tells a good story.

Hosseini isn’t afraid to pile on the emotive material, and most of the time he manages that without tipping over into corny or melodramatic, but towards the end of the book he did trigger my own personal cynic a couple of times. There’s a confrontation with a member of the Taliban in Afghanistan where the coincidences got a bit too Hollywood for me, and I never quite got pulled back into the book again in the same way after that. I also think he fluffed the last few pages.

So having been thoroughly gripped by the book initially, I was a bit disappointed at the end; even so I would recommend it.

» the photo of boys flying a kite in Kabul is AFG_20071109_169.jpg, posted to Flickr by AndyHiggins.