I wouldn’t normally rush to read a chess-themed self-help book, which is more or less what How Life Imitates Chess is. But, you know, it’s Garry Kasparov! The Beast of Baku!

Kasparov seems to have impressed himself on my imagination surprisingly powerfully, considering I’m not much of a chess player. Although I’ve never taken chess seriously, there was a time when I played quite a lot. At school there were a limited number of places to go at lunchtime when the weather was bad; I used to go to the chess room. Even at the peak of my chess-playing powers, I was pretty rubbish, but there wasn’t a great depth of talent at the school, so when they were short of people I would be drafted in to play board eight for the chess team. As far as I can recall, the chess team didn’t win single match in my time at the school, so it wasn’t much of an achievement.

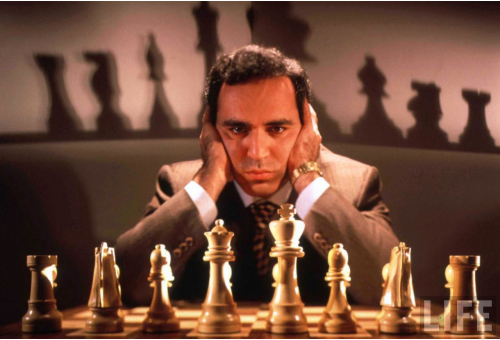

At that time Kasparov was the towering figure in chess, and however casual my own chess was, it was hard not to be aware of him. He was the last of the great Soviet chess champions, with all the Cold War mystique that came with that, and he looked the part with the incredible intensity of his gaze and his heavy eyebrows. On top of that there were the matches against a sequence of IBM supercomputers which seemed like such a symbolic moment in the dawning computer age.

And there was the world championship match against the English player Nigel Short, at least some which was broadcast live on Channel 4, hosted by Carol Vorderman of all people. Sadly none of it seems to have made it to YouTube, because I’d be fascinated to see what it looked like. I remember they had a phone vote for the public to suggest the next move, at which point a couple of Grandmasters would explain why the public was an idiot.

So when I was looking for books from the former Soviet republics for the Read The World challenge, it occurred to me that Kasparov might have written an autobiography which I could read as my book for Azerbaijan. Instead I found How Life Imitates Chess, which uses examples from Kasparov’s chess career as well as business and history to illustrate points about, for example, the value of preparation, and analysing your own weaknesses.

As long as he’s talking about chess, I found it really interesting. The psychology of chess, the different approaches different players take, the preparation that goes into a big match at the top level; when he’s talking about chess, he’s engaging and insightful. The self-help aspect I found less convincing.

Partially I suspect that’s because, despite the long history of chess metaphors, chess isn’t actually a very good model for many other human activities. It’s a completely zero-sum game; for one player to win, the other has to lose. Each chess game starts in exactly the same way, with both players having exactly equal resources and position save only the advantage of playing white. There is no unknown information and no element of chance. It is exceptionally well-suited to rigorous analysis, with information about past performances available with an accuracy that makes baseball statistics look vague and wishy-washy.

These qualities are what make it such a fascinating game, but they are also ways in which it is quite unlike, say, running a business. And businessmen are pretty clearly the intended market; it’s aimed at MBA types who want a change from Sun Tzu. That’s made explicit by the subtitle of the US edition (How Life Imitates Chess: Making the Right Moves, from the Board to the Boardroom) but not, interestingly enough, the UK edition (How Life Imitates Chess: Insights into life as a game of strategy).

I also think his heart isn’t really in it. His examples from business and history are very obvious ones and he doesn’t make much attempt to develop them in any detail; his conclusions are plausible enough but often a bit superficial. I don’t think this book was born out of a deep desire to teach people ‘lessons about mastering the strategic and emotional skills to navigate life’s toughest challenges and maximise success no matter how tough the competition’, as the blurb puts it. It was written to make money from Kasparov’s reputation. I gather from the book that he has been working the circuit giving talks to businessmen and the book was presumably born out of that. It feels like it is fundamentally a sideline for him compared to his real passions of writing about chess and campaigning in Russian politics.

But, still, I thought it was well worth reading for the chess bits, which he manages to make interesting and informative while requiring no real chess knowledge in the reader. I would have preferred a straight autobiography, but I still enjoyed the book. I was irritated to realise after I bought it that it was ‘written with Mig Greengard’, because it makes it unclear how much of what you’re getting is Kasparov and how much is the ghostwriter, but I will still be counting it as my book from Azerbaijan for the Read The World challenge.

» The photo is from Life magazine, as hosted by Google.