This Earth of Mankind is the first novel of the Buru Quartet, so called because it was composed when Pramoedya Ananta Toer was a political prisoner on Buru Island in the 60s. I say ‘composed’ rather than ‘written’ because the first version of it was told orally to his fellow prisoners. He had apparently just about finished the research and planning when he was arrested and all his notes and books were destroyed.

Which is an immediately intriguing back-story, although the relationship between the novel and his imprisonment is not particularly direct, in that Pramoedya was imprisoned by Suharto’s military dictatorship as part of an anti-Communist purge, whereas the novel is set at the very end of the C19th — 1898, in fact — in a Java which is part of the Dutch East Indies.

Still, it is, among other things, a clearly political novel; it deals with the political awakening of a young man growing up in a society structured as a formal racial hierarchy, with ‘Natives’ at the bottom, ‘Pures’ (i.e. Europeans) at the top, and a layer of ‘Indos’ (Indo-European, mixed race) stuck in the middle, operating as a local elite.

The hero of the novel is a Native, but an unusually privileged one; because of the importance of his family, he is the only Native* at an elite high school for Europeans and Indos. So he’s awkwardly positioned in between worlds, brought up to believe that his European education makes him better than other Natives. But of course when he comes into conflict with the establishment, he discovers how fragile his privilege is, and how much he is dependent on the goodwill of the colonial powers.

I enjoyed it; it reminded me rather of one of those European novels from between the world wars, with a whiff of melodrama, and characters having long wordy conversations about ideas. Slightly old-fashioned, but in a good way. I’m certainly tempted to pick up the second in the quartet.

This Earth of Mankind is my book from Indonesia for the Read The World challenge.

* it feels very weird to keep capitalising ‘Native’ like that, but I’m following the practice of the novel, or the translation, which capitalises the racial terms to emphasise their formal legal status.

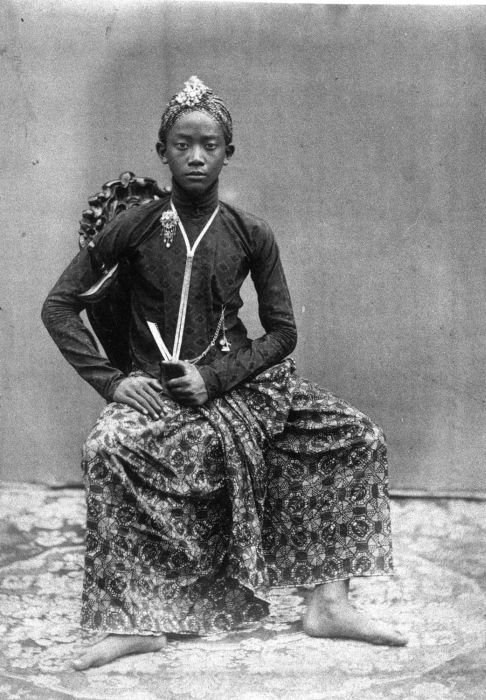

» The photo, by Isidore van Kinsbergen, is from Wikimedia, and according to Google Translate, it is Raden Mas Kotar of the court of Sultan Hamengkoe Buwono VI of Djogkakarta. it’s from 1870, so it’s about 30 years too early, but hey-ho.