The last two films I went to see at the LFF were Target, a Russian film directed by Alexander Zeldovich, and a documentary abou the recent Egyptian revolution called Tahrir 2011: The Good, the Bad, and the Politician.

They don’t have distribution for Target in the UK at least, so I don’t know how likely you are to get to see it, but if you’re the kind of person who cares about such things I should warn now: SPOILERS.

Target is science fiction, from the philosophical end of that genre rather than the lasers and bug eyed monsters end. It’s set in a near future which is described in the LFF catalogue as ‘dystopian’, although I’m not sure that’s quite right: it’s quite hard to tell exactly what kind of society they live in, because the focus is quite narrowly on a group of wealthy Muscovites. There’s some sign of serious wealth inequalities, government corruption and a trashy media culture; but by those standards, Russia is probably a dystopia already. There are also hints of some kind of odd, bureaucratic, government enforced social hierarchy, but it’s never really explained in detail.

The film centres around a group of people who go out to a site way out in the Russian steppes to have a treatment which is supposed to be rejuvenating; it becomes apparent that the treatment actually stops ageing altogether, but it also makes them slightly mad: full of energy but manic and impulsive. Most of them self-destruct, including two who die and two who have to flee the consequences of their actions.

There were things to like about the film: it often looks great, for a start. One of the characters works as customs on a massive 12-lane motorway packed with heavy goods vehicles travelling between Europe and China, which looks spectacular on screen. And the landscape out on the wilds were they get the treatment looks amazing too, especially in the final shot of the film which is stitched together out of three separate shots, the first of which is, they think, the longest single tracking shot in cinema history. And there are some nice set pieces, including scenes of a trashy celebrity cooking show, manically presented by one of the main characters.

And I rather liked the fact that the film had unlikeable characters and a shortage of happy endings. Although that fact is only noteworthy because the bulk of commercial cinema is quite so incredibly conventional and limited.

But in the end 2½ hours was too long. It almost always is, really; at least at the theatre you get an interval so you can stretch your legs and relieve your bladder. Not that it was a slow film — it’s not 150 minutes of meaningful silences, thank God — there was just a lot of material. Too many subplots. And so by the end I was losing concentration and finding my stiff buttocks increasingly distracting.

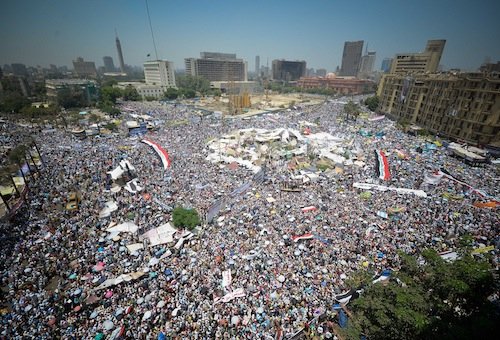

Tahrir 2011 is actually three documentaries made by different people and stitched together — hence The Good, The Bad, and the Politician. The first of them, ‘The Good’, is a fairly nuts and bolts telling of what happened in Tahrir Square this spring, which combined interviews with people who took part and lots of footage filmed at the protests. It’s a fairly conventional documentary, but the events were so amazing that it is riveting to watch. Fascinating and moving.

‘The Bad’ is made up of interviews with members of the police and security services, asking for their account of what happened. Potentially that’s a fascinating subject, but it’s less successful than it could be because they obviously found it very difficult to find anyone willing to talk to them — some of the interviews are conducted in silhouette — and the interviewees are obviously very conscious of finding themselves on the wrong side of history, so they are understandably cagey and defensive.

‘The Politician’ is a portrayal of Hosni Mubarak, framed as an attempt to find out how someone who came to power as a liberal, reforming figure ended up as a dictator. It attempts to present it in a fairly tongue-in-cheek, jokey way, broken into a list of ten items with little animated inserts between them, like a Channel 4 list program. But it doesn’t really come off, and by the end I was falling asleep.

» The photo ميدان التحرير يوم الجمعه ٢٩-٧-٢٠١١ is some rights reserved by أحمد عبد الفتاح Ahmed Abd El-fatah.