I actually went to see this exhibition about a week or so ago, but I’ll just jot down some belated impressions. It is, as the title suggests, a historical survey of watercolour painting, from the medieval to the present.

There are only a handful of medieval pieces, bits of illuminated manuscript, which just serve as a reminder that, although they are not what we usually think of as ‘watercolour’, that is technically what they are.

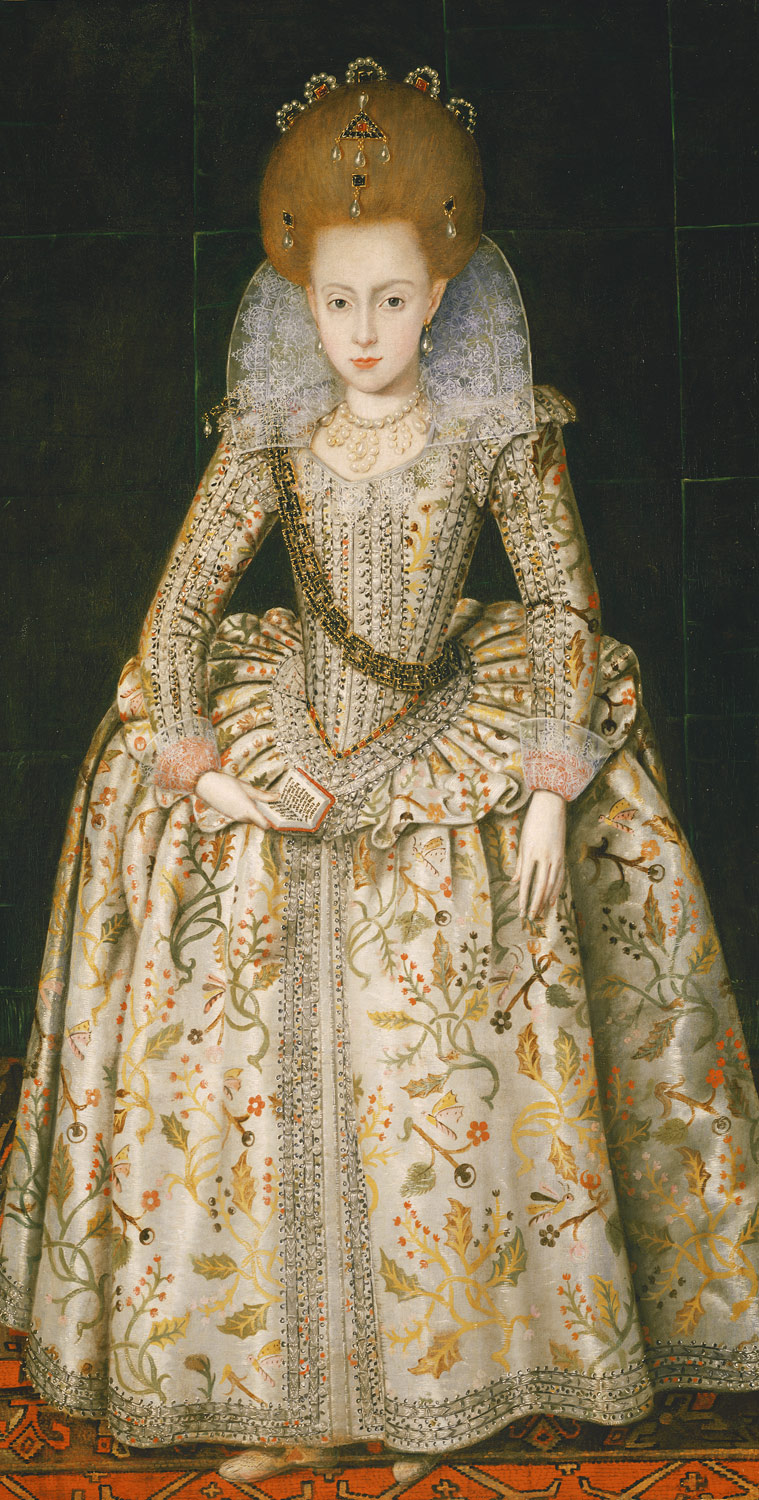

The exhibition makes the interesting point that originally watercolour was mainly seen as an adjunct to drawing: a work would be drawn in pencil or ink and then effectively coloured in, sometimes just with a few hint of colour to liven the drawing and sometimes in a more thorough way. So many of the early pieces are technical works of one kind or another: costume designs for Elizabethan masques, maps, plans of fortifications, as well as a few specific uses like portrait miniatures.

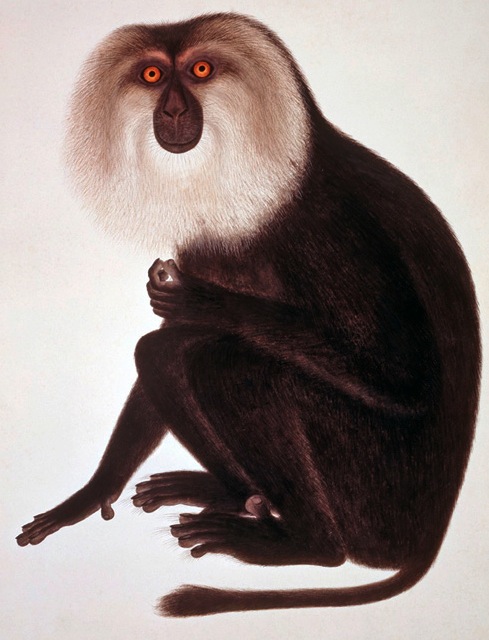

That technical aspect leads on to what is probably my favourite room of the exhibition, a room of scientific illustrations; especially botanical illustrations but also birds and mammals. Many of these were lent by the Natural History Museum or Kew, which is a clear sign that they were not originally created as Art, but they are gorgeous things. It even included some lovely C19th paintings of rock types — each one is a lump of rock on a plain white background, and they look like an elegantly minimalist conceptual art project.

After that we get into watercolour as an artistic medium in its own right. This includes plenty of ‘typical’ watercolours — landscapes, basically — but also a variety of paintings chosen at least partially to challenge that stereotype. So we have a room of war paintings, a room of ‘visionary’ paintings, a room of exhibition watercolours (i.e. large-scale C19th narrative paintings designed to compete with oil paintings for gravitas), and a room of contemporary work using watercolour.

My single biggest problem with the exhibition is that C19th British painting is not something I particularly enjoy. And that was the golden age of watercolour. So the aesthetic of the paintings was more off-putting than anything to do with watercolour as a medium. The exhibition watercolours seemed particularly pointless. I don’t like Victorian narrative painting and find the Pre-Raphaelites exceptionally noxious; seeing them painted in watercolour instead of oils didn’t make them any more likeable. Especially since there was no obvious attempt to make a virtue of the different medium: rather they seemed to be straining to make watercolours look as much like oil as possible.

And some of the paintings had clearly faded, which is the great technical problem of watercolour as a medium. There’s nothing much you can do about that, but it is a pity. There was a painting of some sun-drenched imperial outpost (Egypt? India?) which just didn’t look very hot, and I think it had probably faded a bit. So the shadows weren’t as dark, and the tones weren’t as warm.

As you can tell, I wasn’t blown away. But every room had something of interest and something covetable. And every so often there was a painting which was gorgeous and which could only have been done with watercolour: liquid and light and translucent. So it’s well worth a visit.

» The painting of the Lion-haired macaque, Macaca silenus, is by an unknown Chinese artist working for John Reeves, who employed locals to paint the specimens he was collecting while working in Canton from 1812-1831. That particular work is not in the Tate, though they do have a different monkey from the Reeves collection, lent by the NHM.