A bit of an exhibition round up. This is not, as you might think, four exhibitions, because at Dulwich Picture Gallery at the moment they have a combined Cy Twombly/Nicolas Poussin exhibition. Which might seem like a rather odd choice at first glance, since they lived 330 years apart and one of them painted highly controlled classical paintings and the other did scrawly abstracts.

But there is a kind of logic to it. Both of them moved to Rome at the age of about 30, both use lots of classical references in their work, and Twombly specifically referenced Poussin in several paintings, most notably by painting a large group of four paintings called the Four Seasons, a subject Poussin painted 300 years earlier.

And while I don’t think it was exactly revelatory to see them together, it’s always interesting to explore these kind of comparisons, as an intellectual parlour game if nothing else. I guess you could argue that the Poussins brought out a controlled, restrained quality in the Twombly, for example, but it’s rather an elaborate way to make such a straightforward point. I did find myself warming to Poussin more than usual, though. Clearly he’s a great painter, but generally I find his work a bit sterile. But being displayed among modern paintings did at least make the paintings seem a bit fresher.

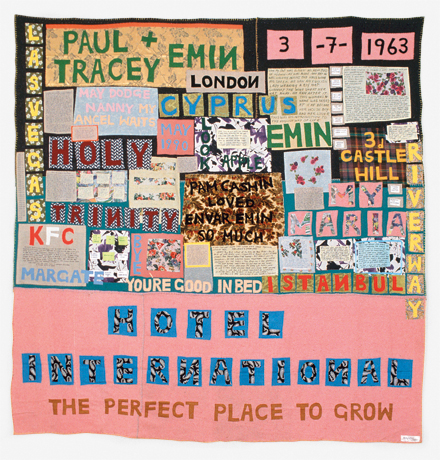

Meanwhile the Hayward is holding a retrospective of Tracey Emin. I went into it with mixed feelings. She has attracted so much bone-headed mockery from the media over the years that I’ve always felt the need to stick up for her… despite not actually liking her work that much. But seeing it all together it does hold up pretty well. The caricature is that she just splurges her personal life uncontrollably into her work for shock value; and that’s not completely unfair. But of course the execution is what matters, just as a confessional memoir could be good or bad could be good or bad depending on who wrote it. And at her best — some of the appliqué blankets, the video work — Emin’s work is sensitive and intelligent. On the other hand, by the time I had gone all the way round the exhibition, it was also starting to feel a bit repetitive. So she’s still not exactly my favourite artist, but I enjoyed the show well enough.

And at the Royal Academy is an exhibition of C20th Hungarian photography. Why Hungarian photography? Well, because five of the most notable photographers of the C20th — Brassaï, Robert Capa, André Kertész, László Moholy-Nagy and Martin Munkácsi — were all Hungarian. So they provide the core of the exhibition, but other, less famous people are included as well. In some ways the exhibition is about Hungary, with striking photographs recording the various wars political upheavals that engulfed the country, but it also includes many taken in other countries: Brassaï photographs of Paris nightlife, or Kertész shots of New York.

If there is anything distinctively Hungarian about the work, I couldn’t particularly see it. It did feel very European, somehow, and it reminded me again how much my idea of Europe was shaped by the Iron Curtain growing up. Austria ended up on one side of it and was therefore a ‘real’ European country; Hungary was on the wrong side and was part of some shadowy other Europe. And 20 years after the fall of communism, that sense of them not being part of the European mainstream still lingers. I don’t know how much that’s just me showing my age; people just out of university now, who were two three when the Berlin Wall came down, hopefully see the continent rather differently.

Anyway, geopolitics aside, the exhibition is definitely worth going to because it has some very fine photographs in it.

» The Triumph of Pan is by Nicolas Poussin; Hotel International, 1993, © Tracey Emin; Greenwich Village, New York, 30 May 1962 is by André Kertész.