There was the first of a three-part series on TV tonight called Make Me A Christian. A group of volunteers, including a lap-dancer and a Muslim convert, are given a three-week course in Christianity by four ministers of various denominations. I watched about 20 minutes of it before I lost patience; it’s an idea that could make an interesting piece of television but in practice it both bored and irritated me.

But one particular idea requires comment: that the UK is a ‘Christian nation’ built on ‘Christian principles’. I don’t think it’s true that any of the important principles that the country is built on are particularly Christian, as it happens, but that’s not the point I want to make.

It is true that, for over a thousand years, the vast majority of the inhabitants of these islands have been Christians. A comfortable majority of British people still are. So, historically and demographically, there is an obvious sense in which it is true to say that the UK is ‘a Christian country’.

But you could use exactly the same arguments to say this is a white country. And if someone was to start saying that the UK is a White nation, built on White principles, we would all immediately understand that their intention was to exclude and belittle.

I know the analogy is not perfect. And I’m not going to claim that, as an atheist, I feel like I’m the victim of any terrible prejudice (though if I was Hindu, Muslim or Jewish I might feel differently). But when an evangelical preacher like the presenter of Make Me A Christian describes the UK as a ‘Christian country’, I’m pretty sure he’s suggesting that his claim to Britishness is better than mine.

I do not accept that this is true.

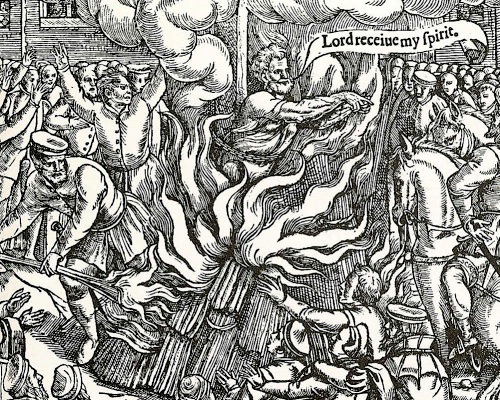

» The picture is of a Christian being burnt by Christians because of his Christian beliefs; an example of the Christian principles so important to British history.