I’ve just read two books for the Read The World challenge; one of them, Life in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, represents the downside of the challenge. It was somewhat interesting, but to be honest, reading it felt like doing homework. And there have been quite a few books which were either boring or just embarrassingly bad. Overall, though, those have been balanced out by all the engaging, interesting books which I never would have read without the challenge.

And, just often enough to keep me going, there are books which are genuinely brilliant; The Ice Palace is one of those. It’s a novel about an eleven-year old girl, Siss, and those weirdly intense childhood friendships, and suspense, and uncertainty, and loss. And it unfolds over the period of one Norwegian winter, so it all takes place in a setting of ice and snow, of darkness and silence.

The most important thing to say about it is that it is a beautiful piece of writing; hats off to the translator, Elizabeth Rokkan, for making the English beautiful. The most obvious thing to pick out is the physical descriptions, of landscape and weather, but I also think the portrayal of Siss’s interactions with the world, and her tightly wound inner life, is nuanced and convincing.

I was saying the other day, in the context of Fernando Pessoa, that there is something of a divide among readers between those who care about prose and those who care about narrative. It’s an oversimplification, but I think it’s a useful one. I am generally reading for the prose, not the plot; but The Ice Palace strikes me as a wonderful example of the narrative working to enhance the pleasure I get from the prose.

Normally when we praise something as having a good plot, I think it suggests ingenuity and intricacy. But this has a very simple plot; by thriller-writer standards, it barely has a plot at all. But what it does have is a very effective narrative structure. The book revolves around one key event, fairly early in the story, which we know more about than the characters, and which creates a situation which needs to be resolved somehow. And that creates enough tension and uncertainty to drive the rest of the book, and means that the eventual resolution, when it comes, feels like an end-point, a closure.

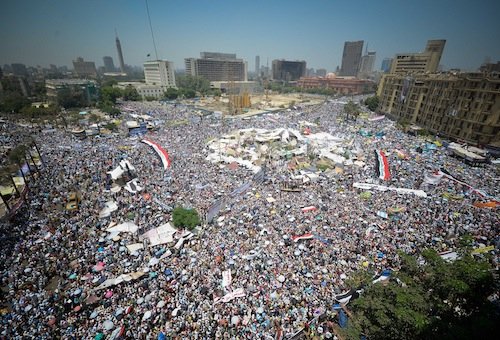

» The photo, On a windy day 1, is © Randi Hausken and used under a CC by-nc licence.