Having written a whole post the other day about how much I wanted field guides on the iPhone and was willing to pay good money for them, I was pleased to hear that a new field guide was available in the App Store: Butterflies of Britain and Ireland (iTunes store link).

It’s an interesting reflection on how much I expect to pay for iPhone apps that a price of £9.99 seemed quite a lot, especially since I just paid £13.49 for a field guide to the butterflies of Europe that I’ll probably use about twice a year at most. Perhaps it’s because I just ordered that book (which hasn’t arrived yet) that I slightly balked at buying another field guide to butterflies. They’re not my main interest, after all. Still, by any reasonable standards a tenner isn’t a lot of money.

I haven’t actually used it in the field yet, but here are my immediate impressions. On the positive side, the content is excellent: high quality and comprehensive. My slight reservations are to do with the app’s usability as a field guide. I’ll give you a quick tour of the way the guide works and then explain what I mean.

It opens with a list of butterflies, which can be sorted either taxonomically or alphabetically:

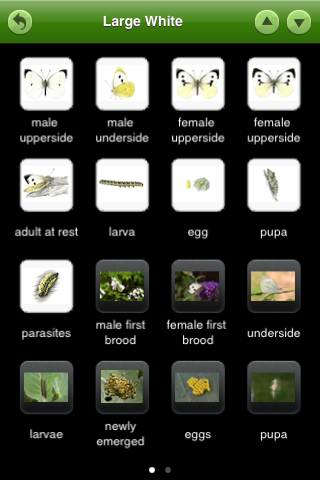

This list doesn’t scroll quite as smoothly as it might, btw, but that’s a fairly trivial point. When you select a species, you get a screen like this:

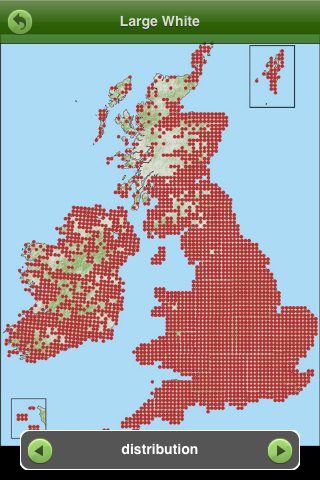

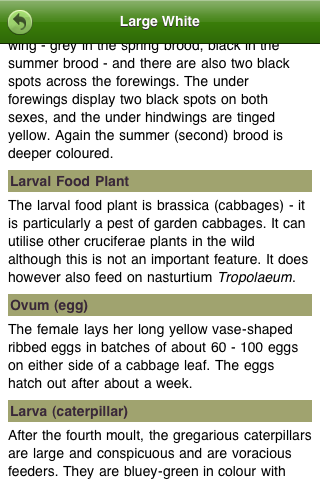

As well as illustrations of the adult butterflies, it also includes the eggs, caterpillars and cocoons, plus a selection of photographs, a distribution map, a calendar, and a text description for each species. Te arrows in the top-right corner move between species.

The illustrations are by the excellent Richard Lewington.

You can flick from one picture to the next within a species, and zoom in on the illustrations or turn the phone to see them larger in landscape mode. In fact it behaves pretty much like the iPhone’s built-in Photos app, which is effectively what it is.

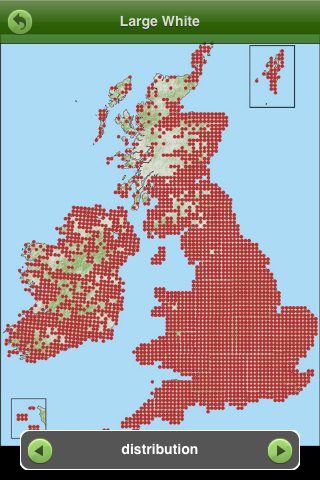

There are illustrations of male, female, upperside and underside, and sometimes variant forms. And here’s an example of a map:

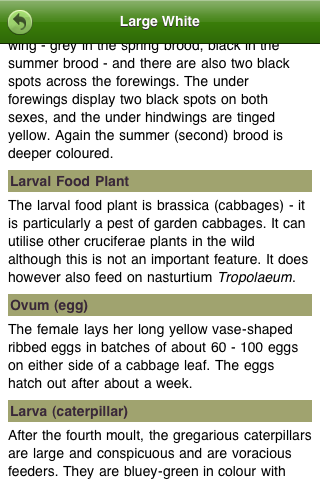

The text is also very thorough:

As you can see, the content is really impressive: detailed, comprehensive and of high quality. I don’t have the expertise to judge the accuracy of the details, but it all appears to be very professional. Incidentally, I suppose one advantage of an electronic guide is that if people do spot any inaccuracies, they can be corrected via a software update.

But as I say, I don’t know how easy it would be to use as a field guide. If you were on a walk in the country, saw a butterfly and wanted to know what it was, it wouldn’t be that easy to quickly see what the possibilities are. There’s no easy way to compare the illustrations or information between two different species. Certainly you don’t have several illustrations on the same page in the way you would with a paper field guide, but also there’s no easy way to flick quickly back and forward between two or three species. You can’t skim through the information.

I don’t want to sound too negative: part of the problem is the fundamental limitations of the technology, particularly the size and resolution of the screen. And it’s still early days; I’m quite sure that over time developers will work out ways to make these apps more usable. The kind of key which is sometimes used for wildflowers, which uses a series of questions to help find the right species (is the stem smooth or hairy? are the leaves in pairs along the stem or alternating?) seems well suited to the iPhone, for example.

For this particular app I would ideally try to make the main screen for each species more informative at a glance: perhaps with a kind of summary screen showing two or three pictures of the adult butterflies — male and female or whatever is appropriate for that species — and a very rough distribution map. It would be a bit crowded and the pictures wouldn’t be very big, but it would be just enough information so you could quickly see whether you wanted to look in more detail or move on to another species. Then you could swipe the screen left to reveal the species screen as it is now, and drill down to find all the juicy details.

So the main species screen could look something like this (apologies for the clumsy mock-up):

And then you swipe across, or hit a button or whatever, to get the species screen as it is now, with all the more detailed information.

Anyway, I don’t mean to be too picky; as much as anything I’m just thinking out loud because I find it interesting. And despite the pickyness, I’m really pleased to see a British field guide in the App Store, and pleased that it has such high quality content. Hopefully it’s the first of many.