This is my book from Benin for the Read The World challenge. I ordered it because I fancied a change from post-colonial fiction, and then regretted it almost immediately; I’ve always been a bit ambivalent about philosophy as a discipline.

Actually, though, I found it interesting and it really did make a nice change. It was first published, as Sur la “philosophie africaine”, in 1976, and is largely framed as a response to earlier works in the field. So it provides an interesting window into a discussion I knew nothing about.

Obviously it’s a narrow window, entirely shaped by Hountondji’s framing, and I don’t have the knowledge to judge how fair and accurate his presentation is. But it still offers an insight into something that would otherwise have passed me by.

The tradition he is arguing with is a kind of ethnological idea of philosophy, where for example, Bantu cultural ideas about death and morality and what have you were investigated, arranged into a system, and then presented as ‘Bantu philosophy’. Hountondji argues that this is not only a misapplication of the word ‘philosophy’ but a damaging one. Rather, ‘African philosophy’ should refer to philosophical works written by Africans; the same thing, in fact, as philosophy from anywhere else.

I was very much predisposed to agree with this argument: so much so that I felt the need to step back every so often and play devil’s advocate. Not because I had any long-standing opinions about African philosophy, of which I was completely ignorant, but because I have a long-standing peeve about the vague, hand-wavy way people use the word ‘philosophy’. It’s rather like ‘poetry’ in that respect.

Still, you can understand the impulse that led people to things like ‘Bantu philosophy’. Given the context of colonialism, there is/was a value in any assertion that Africans are capable of interesting thought that is distinct from that brought by colonialists and worthy of study in its own right.

Whereas if you insist on the narrow definition of philosophy, then there is almost no African philosophical tradition; certainly very little ‘authentically African’ philosophy that precedes or is separate from the stuff brought over by Europeans. That’s just an artefact of an oral society. It’s perfectly possible to do philosophy without writing it down — it was good enough for Socrates — but it doesn’t survive; we only know about Socrates because of Plato.

But things like ‘Bantu philosophy’ are a bad solution to that problem. Firstly, because it perpetuates the idea that Africa is so exotic/primitive/whatever that all our approach to it must be through an ethnographic lens, just as African sculptures end up in a different museum to the Picassos and Modiglianis that they inspired.

One result of that is that it strips away any sense of individual creativity: those African sculptures get labelled with a tribe and a place, and not the name of the individual sculptor. Similarly, ‘folktales’ get stripped down to a simple one-page version based on what the researcher thinks is the kernel, and both the name and the creativity of the individual storyteller get lost. Which of course is pretty much the opposite of how we treat poets, artists and philosophers in our own culture, where if anything we are overly obsessed with the idea of individual genius.

And lastly, the very process of taking a lot of different sources — traditional stories, received opinion, religious ideas — and systematising them into a coherent philosophy is itself pretty dubious. Hountondji argues, I think correctly, that the systematiser is imposing his own ideas far more than he is revealing something which is there already.

All this stuff is no doubt old news to people in the field, but I found it interesting to read about.

In the second half of the book, Hountondji looks at some case studies. I have to admit, I skipped over most of the stuff about Anton-Wilhelm Amo: he’s an interesting figure, an African from what is now Ghana who somehow ended up teaching philosophy in German universities in the 1730s, but his surviving dissertations are minor contributions to the debate between the vitalists and the mechanists; I have no idea what that means, and frankly I don’t care enough about C18th philosophy to try to make sense of it.

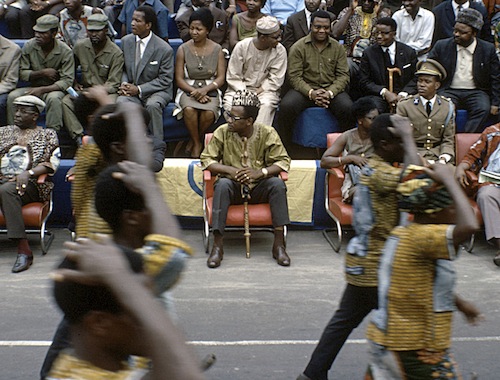

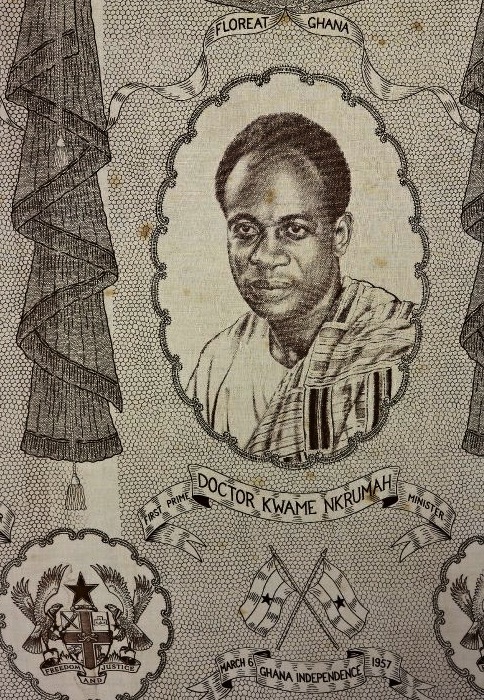

But I did read Hountondji’s analyses of Kwame Nkrumah’s thought, which was rather more interesting, not least for some second-hand insight into another set of arguments about which I was ignorant: about class, colonialism, capitalism, Africanism and so on.