I went to the Rothko exhibition at Tate Modern today. The show is of his ‘late series’: the centrepiece is the Seagram Murals (i.e. the group of dark Rothkos which have been in the Tate for years, plus some related works that normally live in Japan), but there are also some other groups of works (the ‘Black-Form’, ‘Brown and Grey’ and ‘Black on Gray’ paintings) as well as related odds and ends.

It’s quite suggestive, I think, that the Seagram murals were commissioned for the Four Seasons restaurant in the new Seagram building in New York, and that they ‘never reached their original destination, after Rothko decided that a private dining room was an unsuitable environment to experience his paintings.’ Because with these big colour-field paintings there is always going to be a delicate path to tread between art and interior design. And indeed you can see why the restaurant might have wanted them: they would have added a touch of modernity and sophistication without actually challenging the air of hushed pomposity which is so important to an expensive restaurant.

But although they could serve as interior design, they are certainly more than that. They are seductive pieces, and they do reward patient contemplation. Partially that’s because they are much more carefully made than the simplest description of them might suggest: a painting may be, in the most reductive terms, a big maroon blob on a red background, but they have more presence than that. Apparently he painted them with many many layers of very thin paint, and they remind me slightly of fine Japanese lacquer; the way a plain red and black rice bowl can be a deeply desirable object because of the texture and way the light falls on it.

And despite what I said in my last post, and despite the funereal colour-schemes, they aren’t gloomy. They are whatever the antithesis of frivolous is — suolovirf — but half an hour spent in their company was restful rather than depressing. They are beautiful things: big, but subtle in their colours and textures.

Or at least the Seagram murals are; some of the others were less exciting, most notably the ‘Black on Gray’ works, all divided into an area of black at the top and pale grey below. Those ones managed to be exactly as boring as the description suggests.

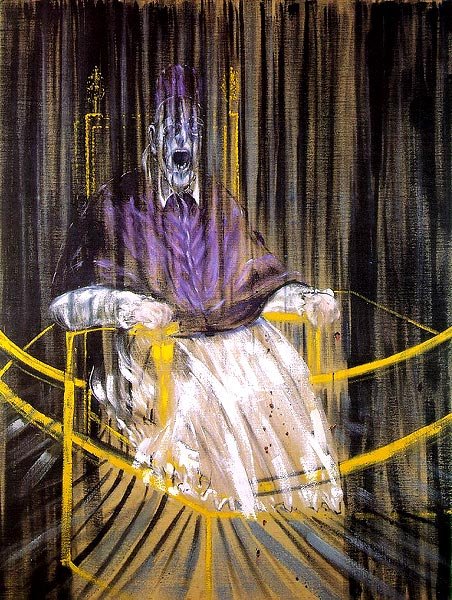

» The painting is ‘Red on Maroon Mural’, from the Tate. I’ve taken it from the exhibition website, which as usual with the Tate, is very good, so do go and take a look.