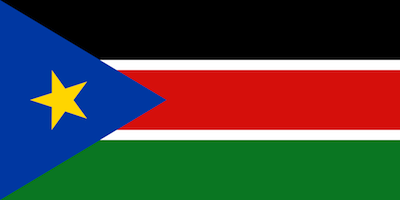

I’m currently reading Only Yesterday, S.Y. Agnon’s novel about Jewish settlers in Israel before the first world war. And so far I’m enjoying it, apart from one thing. It’s in a handsomely made edition published by Princeton University Press, on high-quality paper, with large type, set with a generous amount of leading and plenty of white space. In other words: it’s fucking enormous.

There it is with my old Penguin Classics edition of Tristram Shandy for comparison.

Ah, but, I can hear you saying, you’ve used the wide-angle effect of the camera to exaggerate the difference in size! And there’s a degree of truth to that, so here’s a different angle:

The Agnon is 5.2cm longer, 4.2cm wider and 1.6cm thicker. The result is that it is nearly three times the volume, and over three times the weight (930g; i.e. over two pounds).

Ah but, I hear you say, you are still being unfair! Clearly the Agnon is a much longer novel!

You might think so, but no, it isn’t (thank heavens; Tristram Shandy isn’t exactly a pamphlet). It’s hard to compare exact word counts, but Tristram Shandy has 659 pages; Only Yesterday has 652. And they have the same number of lines per page and at least roughly the same number of words per line. I counted.

Seriously, though, whose idea was it to inflict these ludicrously big books on us? I spent a large chunk of my youth with one Penguin Classic or another tucked in my jacket pocket; the Agnon isn’t just too big to fit in a pocket, it’s close to being too big to read comfortably at home on a sofa.

The pointlessly large paperback seems to be a particular weakness of American publishers — insert your own joke about obesity or steroid abuse here — but I think it’s part of a general trend. I have a load of old Penguin Classics from the 80s and 90s, and at some point they changed the format. Inevitably they got bigger, by about 2cm in each direction. That’s not as gargantuan as the Agnon, and thankfully they’re still printed on nice thin paper so they’re not any fatter, but it’s probably too big to fit in a pocket.

And if you’re wondering, yes I do dislike hardbacks for exactly the same reason. They’re less comfortable to read, and they take up too much room in your bag or on your shelves.

I think I understand the logic for the publishers, mind you; they need to charge a lot of money for these books, particularly if they’re not expecting to shift a lot of copies. And physically making the book is a fairly small part of the overall costs, so why not spend a little extra producing an object which feels substantial and high quality; that way people feel more like they are getting their money’s worth. The list price for Only Yesterday is $32.50; at that price perhaps people want a lot of paperback for their money.

But it’s madness. Why can’t publishing learn from the tech industry? A book is nothing if not a mobile device; and just as each generation of the iPhone is advertised as thinner and lighter than the one before, why aren’t publishers advertising ultraportable novels?

It’s a silly time to be making this argument, of course, because the decision is being taken out of publishers’ hands. There is an ultraportable format of books: it’s called digital. I don’t often carry books around with me any more; instead I have books on my phone. It isn’t the ideal way to read, but it’s zero extra bulk to carry.

But if ink and wood pulp are going the way of the horse-drawn carriage, I just want to say: what I will miss is not big glossy hardbacks, however beautifully designed and printed, but small format mass-market paperbacks printed on flimsy paper. If the invention of the printing press changed the world by democratising knowledge, then the paperback was the apotheosis of that project; the cheapest, most convenient, most accessible way of communicating ideas and literature ever devised.