This is a biography of Charles Darwin’s grandfather. He was a doctor by trade, and one of the most highly rated in the country, but was one of those classic Enlightenment figures whose interests included botany, meteorology, physics, chemistry, engineering, philosophy and just about anything else that came his way. And for a few years he was the most successful and critically acclaimed poet in England.

He seems to have been effortlessly brilliant at everything; the list of inventions and discoveries which can be attributed to him is startling. The inventions include: an improved steering system for carriages, a machine for writing in duplicate, a temperature-regulated system for opening and closing the windows of a greenhouse, a machine that reproduced human speech, an artificial bird, an improved seed-drill, the gas turbine, the rocket motor, cataract surgery and the canal lift. Scientific principles include: the ideal gas law, the chemical composition of water, the structure of the atmosphere, the formation of clouds, the artesian well, and of course evolution.

Even so, there’s a touch of defiance in the book’s full title: Erasmus Darwin: A Life of Unequalled Achievement. That’s because almost everything on that list comes with a caveat of one kind or another. For example, many of them are based on a few lines or a quick sketch appearing in his Commonplace Book or in one of his letters; and while it’s undoubtedly takes a remarkably inventive mind to come up with the principle for the gas turbine a hundred years ahead of its time, if it never gets beyond a quick scribble it’s a very limited achievement. Another example is his improved steering system, which worked by just angling the wheels left and right instead of turning the whole axle. This creates a much more stable carriage and is the principle used by all modern cars. Darwin built a carriage on this model, and used it successfully for decades going over thousands of miles of bumpy roads to visit his patients; but he never made a real effort to market the idea and it died with him.

Which isn’t to say he had nothing to show for his scientific brilliance. He submitted quite a few papers to the Royal Society on subjects like meteorology and geology; he did the first English translation of Linnaeus, and wrote a major book on medicine. But there is no one major achievement you can attach his name to. Partly that’s because he was a very hard-working doctor. Not only did it take up a lot of time; he was also very worried about his professional reputation. Much of his work was published anonymously because he didn’t want to detract from that reputation, and the biggest single factor that prevented him from achieving more as a scientist was probably that he always put his career first.

And when he did commit to major works he didn’t always make the best choices. His translation of Linnaeus’s botanical taxonomy was drudgery really, the scientific equivalent of translating a phonebook, even if it did add a few words to the English language, like bract, floret and leaflet. And his major work on medicine doesn’t hold up at all because, frankly, no-one at the time knew enough about the workings of the human body. No-one knew about germs, microscopes had been invented but weren’t really used, and they had very few treatments that did any good, so they just gave everyone lots of opium.

Comparisons between Erasmus and Charles are inevitable, and it’s tempting to put the difference between them down to personality: to suggest that Charles was less brilliant but made up for it with dogged single-mindedness. Personally I think the financial aspect is just as important. Erasmus and his son Robert were both highly successful doctors and Robert also had a very good eye for investments, with the result that Charles was a wealthy man. If Erasmus hadn’t had to work, who knows what he would have achieved. His medical practice certainly proves he was capable of hard work; his calculations suggest he travelled about 10,000 miles a year, which on C18th roads is a hell of a long way.

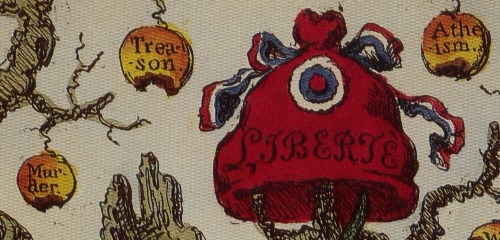

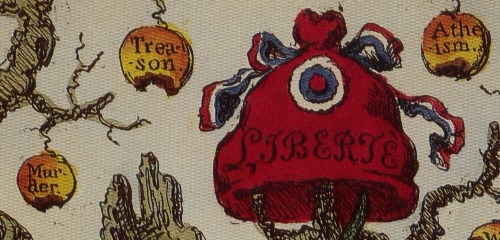

I find the poetry the most interesting thing, though. Science is not a subject that has often been successfully treated in poetry, so someone like Erasmus Darwin writing poems about science is really intriguing. If you have an interest in science and poetry, it’s always fun when the two overlap, as with the reference to Galileo in Paradise Lost. But it’s rare to have poetry written by someone right at the heart of the scientific culture. Darwin’s friends and correspondents include people like Joseph Priestley, Joseph Banks, Benjamin Franklin, James Watt, Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton and Richard Arkwright. He writes about science and technology as a complete insider. And for a few years he was very successful and critically acclaimed, before being left behind by a shift in fashion—he represents everything Coleridge and Wordsworth were reacting against—and in politics. As the French Revolution turned bad, his radical views became a public liability.

So I find the idea of Darwin’s poetry fascinating. I’m undecided about the poetry itself. All the mythological trappings seem so unnecessary, and the ornate style can border on self-parody; one of his particular quirks is phrases like this:

Swords clash with swords, on horses horses rush,

Man tramples man, and nations nations crush

Still, I love the very fact that he’s applying this high style to such non-literary subject matter. In another poem, someone might only apply this kind of language to a subject like a tadpole to make a joke out of the incongruity. Darwin did have a sense of humour, and if not actually tongue-in-cheek, I think the poems are intended to have a fairly light touch; but he seems to be trying to communicate a real fascination and beauty he finds in nature, as in this passage where he is invoking tadpoles and mosquitos as a comparison with life emerging from the sea:

So still the Tadpole cleaves the watery vale

With balanc’d fins, and undulating tail;

New lungs and limbs proclaim his second birth,

Breathe the dry air, and bound upon the earth.

So from deep lakes the dread Musquito springs,

Drinks the soft breeze, and dries his tender wings,

In twinkling squadrons cuts his airy way,

Dips his red trunk in blood, and man his prey.

Is that good poetry? Maybe not. Maybe the style is just a distraction. On the other hand I think you can pick out passages which are more successful, like this:

“Yes! smiling Flora drives her armed car

Through the thick ranks of vegetable war;

Herb, shrub, and tree, with strong emotions rise

For light and air, and battle in the skies;

Whose roots diverging with opposing toil

Contend below for moisture and for soil;

Round the tall Elm the flattering Ivies bend,

And strangle, as they clasp, their struggling friend;

Envenom’d dews from Mancinella flow,

And scald with caustic touch the tribes below;

Dense shadowy leaves on stems aspiring borne

With blight and mildew thin the realms of corn;

And insect hordes with restless tooth devour

The unfolded bud, and pierce the ravell’d flower.

“In ocean’s pearly haunts, the waves beneath

Sits the grim monarch of insatiate Death;

The shark rapacious with descending blow

Darts on the scaly brood, that swims below;

The crawling crocodiles, beneath that move,

Arrest with rising jaw the tribes above;

With monstrous gape sepulchral whales devour

Shoals at a gulp, a million in an hour.

— Air, earth, and ocean, to astonish’d day

One scene of blood, one mighty tomb display!

From Hunger’s arm the shafts of Death are hurl’d,

And one great Slaughter-house the warring world!

I find that to be a strong piece of writing and a striking vision of violent nature. It’s from Canto IV of The Temple of Nature, where Darwin comes within a whisker of stating the principle of natural selection. Here’s another bit from later in the same canto:

“HENCE when a Monarch or a mushroom dies,

Awhile extinct the organic matter lies;

But, as a few short hours or years revolve,

Alchemic powers the changing mass dissolve;

Born to new life unnumber’d insects pant,

New buds surround the microscopic plant;

Whose embryon senses, and unwearied frames,

Feel finer goads, and blush with purer flames;

Renascent joys from irritation spring,

Stretch the long root, or wave the aurelian wing.

“When thus a squadron or an army yields,

And festering carnage loads the waves or fields;

When few from famines or from plagues survive,

Or earthquakes swallow half a realm alive; —

While Nature sinks in Time’s destructive storms,

The wrecks of Death are but a change of forms;

Emerging matter from the grave returns,

Feels new desires, with new sensations burns;

With youth’s first bloom a finer sense acquires,

And Loves and Pleasures fan the rising fires. —

Thus sainted PAUL, “O Death!” exulting cries,

‘Where is thy sting? O Grave! thy victories?’

I love the cheeky jabs at both royalty and religion; firstly in lumping together a monarch and a mushroom as comparable lumps of organic matter, and then the way he implies that acting as compost for plants and food for insects is what St Paul had in mind with ‘Oh Death! Where is thy sting?’ But there is also a kind of slightly nutty grandeur to the poetry.

Some bits of his poems hold up better than others, both scientifically and aesthetically. But I think the best of it is good enough to be worth reading, particularly because the subject matter makes it so unique.

» passages from The Temple of Nature are taken from this site where you can read it in full. The picture of a rocket is by jurvetson on Flickr and is used under an attribution CC licence. The opium poppy is from a C19th German herbal and is used courtesy of Missouri Botanical Garden at botanicus.org under a by-nc Creative Commons licence. The hat is a detail of a Gillray cartoon, the Tree of Liberty, from a page of cartoons from the period at the University of Lancaster.