Last week I went to Blind Light, the Gormley show at the Hayward. Gormley must be the third most famous artist in Britain, I should think*, particularly on the back of two spectacular public works: Angel of the North and Another Place.

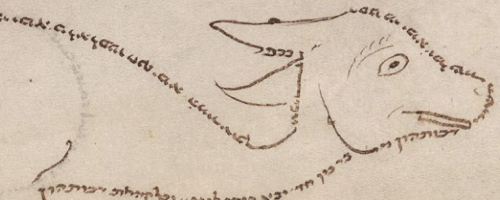

For those of you who don’t know his work—foreigners and the like—he has produced an endless series of variations of the human form; his visual signature is a blank-faced statue, standing rigid with its hands by the sides. I believe most of them are cast from his own body, but any distinctive characteristics are removed to leave a generic male form. The two works I’ve linked to above give you an idea of how he varies the basic template. To accompany the current exhibition, he has created another such installation: a number of life-size male figures, cast in bronze, positioned on rooftops and other prominent places over a 1.5 km radius, all facing towards the gallery.

0706290002, originally uploaded by domeheid.

This installation, titled Event Horizon, is a joy in itself; you start seeing the figures as you walk to the gallery, and then from the various exterior spaces of the gallery you can scan the rooftops of London to look for more of them. All these mute figures watching from the rooftops are almost rather creepy—it’s very Doctor Who—but mainly it adds a touch of magic to some very mundane buildings and creates a striking relationship between the exhibition and its surroundings.

Part of what makes it so good is the sheer scale. It must have been a major undertaking just identifying places to put them, negotiating with the owners of the buildings, and getting them into position. You could imagine an artist doing the same thing but being content to just place half a dozen figures on nearby buildings. Gormley has placed 31 figures (according to Wikipedia); some are so far from the gallery that you can’t even be certain that you’ve identified them correctly.

That commitment, I think, is typical of the artist. With someone whose work has quite such a consistent theme running through it, there’s a risk of them being a one-trick pony, but Gormley doesn’t just have lots of ideas for how to develop his basic theme; he develops and executes those ideas thoroughly. My most frequent irritation with contemporary art is when I feel that it’s under-developed. Half baked. I don’t get that with Gormley.

It helps of course that, being human ourselves, we tend to find the human form endlessly fascinating.

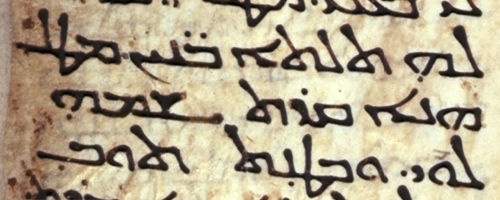

The most striking work inside the gallery is called Blind Light; it’s a glass-walled box, about 10m square, which, with the help of ultrasonic humidifiers and flourescent lights, is filled with bright white fog. Once you enter, visibility is down to a couple of feet, sound is muffled, the floor is wet underfoot; I only walked across the box and then turned round to walk back to the entrance, but still got lost enough that I had to feel my way along the wall to find the door again. Meanwhile, from the outside, you see people’s figures appear as ghostly shadows in the mist.

blind light by _imax, used under a by-nc-nd Creative Commons licence.

What I found most striking was the disjuncture between the immersive, disorientating strangeness of being inside the box and the relative mundanity of what it looks like from the outside. Intellectually you know what it will be like, and you can see other people stumbling around in the mist, but it doesn’t quite prepare you for actually being in there. In a sense this feels like a trick; yes, it’s an intense experience being unable to see where you’re going. Does that mean it has artistic worth or is it just a fairground ride with an arty blurb attached to it?

One point to make is the way it relates to the other work in the exhibition; the box obscures people’s individuality and turns them into shadowy versions of Gormley’s blank-faced statues. And when you’re in there, you become very aware of your own body and your relationship with your surroundings. In the same room there’s a work from 1991 called Sense, a block of concrete with a couple of holes that turn out to be just the ends of a body-shaped void in the block. A model of Gormley’s body was cast in wax, the concrete was poured around it, and then the wax melted to leave the empty space. Blind Light is like a live-action version of the same thing; everyone who walks into it carves out a body-shaped hole in the mist.

There were lots of other works as well which I haven’t touched on; this slideshow from the Telegraph gives you some idea.

*Hirst and Emin.