The President is my book from Guatemala for the Read The World challenge. I’m probably going to count it it towards Scavella’s Caribbean Reading Challenge as well, although I haven’t really worked out my list for that yet. It comes with one high recommendation: Asturias was, as it says on the cover, ‘Winner! Nobel Prize for Literature’.

It is a book about life under a dictatorship; at the beginning a Colonel is murdered under slightly freakish circumstances, and the repercussions spread out from there, starting with the President using the murder as a pretext to target other politicians. The President isn’t particularly about the president himself, but the psychological and social impact on other people of the arbitrary and ruthless exercise of power.

I have to say I was left slightly cold by it. I don’t know if I would have read it any differently if I’d checked to see when it was written before reading it (d’oh!). It turns out it was actually written between 1922 and 1933 (though not published until 1946), which makes some of the stylistic quirks seem rather more radical and others more forgivable.

The things I might need to forgive – i.e. what I found irritating – is a certain overwrought quality to the prose, typified by the plentiful use of ellipses… and exclamation marks! Knowing that the book was written at least four decades earlier than I thought provides a degree of context for that, I think; quite a lot of books from the interwar period have a hint of intellectual melodrama to them. When I was reading it, though, I just thought it might be a very dodgy translation.

And on the other hand, the surreal aspect to the writing – the narrative slips into almost dream-sequence passages, and the action and characterization is sometimes slightly grotesque – is clearly not, as I vaguely thought, a pale imitation of Marquez. Rather, Asturias is probably an important influence on a writer like GGM.

Still, this is all post facto stuff, and when I was reading it I was rather less charitable. It was sporadically brilliant – after reading the first chapter I really thought I was in for a treat – but it never quite gripped me. It follows various intertwined characters, which meant no strong central narrative to pull me back in once my attention started wandering.

Anyway, here’s an extract:

Nothing was visible ahead. Behind them crept the track like a long silent snake unrolling its fluid, smooth, frozen coils. The ribs of the earth could be counted in the meagre dried-up marshlands, untouched by winter. The trees raised themselves to the full height of their thick, sappy branches in order to breathe. The bonfires dazzled the eyes of the tired horses. A man turned his back to urinate. His legs were invisible. The time had come for his companions to take stock of their situation, but they were too busy cleaning their rifles with grease and bits of cotton that still smelt of woman. Death had been carrying them off one by one, withering them as they lay in their beds, with no advantage to their children or anyone else. It was better to risk their lives and see what would come of that. Bullets feel nothing when they pierce a man’s body; to them flesh is like sweet warm air—air with a certain substance. And they whistle like birds. the time had come to take stock, but they were too busy sharpening the machetes the leaders of the revolution had brought from an ironmonger whose shop had been burned down. The sharpened edge was like the smile on a negro’s face.

I think this is a good book which, for whatever reasons, didn’t grab me. Shrug.

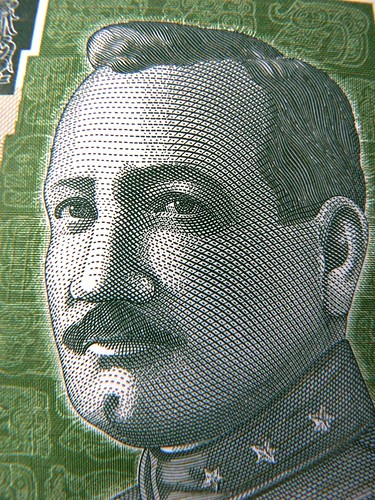

» The picture is of José María Orellana, president of Guatemala when Asturias started writing the novel, as he appears on the one quetzal banknote. It is © Oscar Mota and used under a CC attribution licence.