How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone by Saša Stanišić is my book from Bosnia and Herzegovina for the Read The World challenge. I actually had a different writer in mind — Ivo Andrić, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961 — but when I saw this in the bookshop I switched. Mainly because most of the books I’ve been reading are a few decades old, and it’s nice to find one which is fresh out of the oven (published in German in 2006; the English translation by Anthea Bell in 2008).

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone tells the story of Aleksandar Krsmanović, a boy who is growing up in the Bosnian town of Višegrad but flees with his family to Germany in 1992 to escape the war. Since Stanišić grew up in Višegrad and moved to Germany in 1992 as a fourteen-year-old, I assume it is somewhat autobiographical.

The blurb on the back cover compares Stanišić with Jonathan Safran Foer and David Foster Wallace, which gives you some idea of the kind of writer he is: a clever young man who isn’t afraid to leave evidence of his cleverness on the page. There are sections written in different voices, stylistic quirks, elements you might call magical realist, a bit of a book-within-a-book and so on. In fiction there can be a fine line between overtly clever and overly clever, and for the first few chapters I was a bit unsure which side of the line this book falls, but it won me over.

Here’s a fairly randomly picked passage:

My Nena went deaf the day Grandpa Rafik married the river Drina, face down. The marriage was legal because Nena and Grandpa Rafik had been divorced for years, something unusual in our town. After Grandpa Rafik was buried, they say she said at his graveside: I haven’t cooked anything, I haven’t brought anything, I haven’t put on black clothes, but I have a whole book full of things to forgive. They say she took out a stack of notes and began reading aloud from them. They say she stood there for a day and a night, and word by word, sentence by sentence, page by page she forgave him. And after that she said no more, and she never reacted to any kind of question again.

Nena Fatima has eyes as keen as a hawk’s, kyu, ket-ket, she recognises me before I turn into her street, and she wears headscarves. Nena’s hair is a secret — long and red and beautiful, she gave the secret away to me as we sat outside her house eating börek in summer and feeding the Drina with minced meat. Cold yoghurt, salted onions, the warmth of Nena rocking silently as she sits cross-legged. The dough is shiny with good fat. Nena rocks back and forth and lights a cigarette when I’ve had enough. I am the quietest grandson in the world, so as not to disturb her stillness and our sunset. Sultry heat gathers over the river and looks attentively at Nena Fatima, who is humming as she plaits her secret into a long braid. I don’t laugh with anyone as softly as with my Nena, I laugh with her until I’m exhausted, I don’t comb anyone else’s hair.

As I do the Read The World challenge, various themes are recurring; this is the third book I’ve read (along with My Father’s Notebook and The Kite Runner) which is written by a refugee, starts with nostalgic memories of the home country, and then describes the country collapsing and the refugee experience. It is much the best of the three, I think; I did genuinely enjoy The Kite Runner, but it is deeply emotionally manipulative, like watching a Hollywood film about a difficult subject by a skillful but solidly mainstream director. The kind of glossy film on a ‘brave’ subject which is daring enough to win a few Oscars but which you look back on a few years later and think… meh. How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone is a more interesting book all round; messier, more personal (I think), funnier, sadder. And while I don’t want to overstate the originality of it — it’s been nearly a hundred years since some bright spark invented modernism, FFS — it is at least less of a straight down the line conventional narrative.

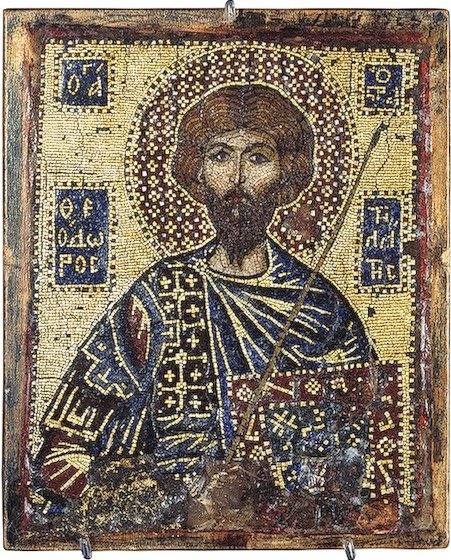

» the photo is of the bridge over the Drina in Višegrad that is mentioned in How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone and is also incidentally the eponymous bridge in Ivo Andrić’s novel The Bridge on the Drina. The photo is © blandm and used under a CC by-nc-sa licence.