-

'Spiegel TV has tracked down rare Nazi TV footage, complete with everything from bizarre cabaret acts to interviews with people like Albert Speer.'

Year: 2008

The final chapter of The Origin of Species — Darwin’s ‘Recapitulation and Conclusion’ — states the case for evolution as well as any short account I have ever read. It’s tightly written, it argues a case, it summarises all the different kinds of evidence and shows clearly why they are important. It’s pithy, confident: great stuff.

Which left me feeling look, Darwin, if you can write like that, why have the previous 400 pages been such hard work? Because he did produce some turgid paragraphs. He’s better when he’s talking about specifics — particular animals and experiments — but when he gets into generalities and abstract ideas, his prose often turns to mush. Here’s a sample sentence:

The forms which possess in some considerable degree the character of species, but which are so closely similar to other forms, or are so closely linked to them by intermediate gradations, that naturalists do not like to rank them as distinct species, are in several respects the most important for us.

OK, that’s not particularly difficult to understand, but it doesn’t have a lot of oomph, either. Not much forward momentum to keep the reader going.

That sentence is taken from the chapter ‘Variation under nature’, and part of the problem in that chapter and elsewhere is that Darwin is struggling against the limitations of his knowledge. Variation and heredity are absolutely central to the idea of natural selection, so of course he has to talk about them a lot; but without knowing about genetics, let alone DNA. And at times he seems to be floundering a bit. I’m very aware, reading it, of how much he doesn’t know; I’m curious how much he felt that lack of knowledge himself. He certainly had enough evidence of other kinds to argue convincingly that all living things evolved from a common ancestor, and that natural selection was a plausible explanation for how it happened; but without genetics there is certainly a jigsaw piece missing.

That’s not the only gap which is obvious with hindsight: for example, he talks about the distribution of species as evidence for common descent, but without continental drift, there are certain details he can’t quite explain. So if someone wanted to understand evolution, they should start with a more modern text. I suppose the question is: why read The Origin at all? Well, the immediate reason I re-read it is that we’re currently building up to Darwin Year. 2008 is the 150th anniversary of the first publication of the Darwin/Wallace theory of natural selection at a meeting of the Linnean Society, and 2009 is both 150 years since the publication of The Origin of Species and also Darwin’s 200th birthday.

Also, it may be hard going by the standards of modern popular science writers, but for one of the key documents in the history of science, it’s incredibly (perhaps uniquely) accessible. I haven’t actually tried reading James Clerk Maxwell’s original papers on electromagnetism, or Einstein’s on relativity, but I don’t think it’s defeatist to say I wouldn’t understand them. Darwin is entirely manageable for a non-technical reader. He uses some technical terminology without defining it, so you might be checking the glossary a bit if you don’t know, for example, that ‘cirripedes’ are barnacles; but the book is mostly dealing with familiar concepts and entities: species and varieties, pigeons, bees, flowers. The only comparison that springs to mind is another book written at the early stages of a science, when scientists were still grappling with everyday concepts and the visible world: Galileo’s Dialogue Relating to Two New Sciences (which, by the way, is well worth reading).

And when Darwin hits his stride, when he gets stuck into the details, the book is still full of interesting material. For example, discussing the means by which plants are distributed between places:

I do not believe that botanists are aware how charged the mud of ponds is with seeds. I have tried several little experiments, but will here give only the most striking case. I took, in February, three table-spoonfuls of mud from three different points, beneath water, on the edge of a little pond. This mud, when dry, weighed only 6¾ ounces. I kept it covered up in my study for six months, pulling up and counting each plant as it grew. The plants were of many kinds, and were altogether 537 in number; and yet the viscid mud was all contained in a breakfast cup! Considering these facts, I think it would be an inexplicable circumstance if water-birds did not transport the seeds of fresh-water plants to vast distances, and if consequently the range of these plants was not very great. The same agency may have come into play with the eggs of some of the smaller fresh-water animals.

That passage is a great demonstration of Darwin’s practical turn of mind. For someone who is known for having produced a famous theory, he was a great experimentalist. Faced with the argument that, for example, seeds couldn’t be distributed on ocean currents because salt water would kill them, he tried the experiment, leaving seeds in salt water for different periods of time to see if they would still germinate. He wanted to know more about the process of selective breeding in domestic animals, so he started breeding fancy pigeons. He wanted to know how inherited instinct could enable bees to make such elaborate and perfect honeycombs, so he provided a hive of bees with specially prepared blocks of wax to see what they would do with them.

If anything the book is more convincing as an argument for the historical fact of evolution — common descent with gradual changes over time — than the theory of natural selection. He does make a good case for natural selection, mainly by analogy with selective breeding in domestic animals, but because he didn’t know about genetics or DNA, there’s an inherent fuzziness about the details right at the centre.

But his argument for evolution is I think particularly strong because he was consciously writing for an audience of educated people who believed in the immutability of species. So he points out that varieties (what we now usually call subspecies) blur indistinguishably into species, so that experts frequently disagree whether to classify them as full species or not. That different continents have basically different flora and fauna; so the animals in the Amazon are related to those of the Andes rather than those of the Congo, even though the Congo is a much more similar habitat. And oceanic islands normally have very limited fauna; that what they do have tends to be those animals that can fly (insects, birds and bats, but not other mammals) or can survive salt water (reptiles but not amphibians). And again, that the inhabitants of those islands are related to the inhabitants of the nearest continent, even when the island habitat is quite different. All these facts are easily explained by evolution; there is no reason why any of them would need to be true if species were created in place.

» To illustrate this post I thought I’d break away from the most obvious stuff (Galapagos finches etc) to pick some of the other things Darwin studied: orchids, earthworms and barnacles. The orchid photo is one I took in Crete; the earthworm is by Jonathan Spangler and is used under a CC by-sa licence; the goose barnacles are by pshab and used under a by-nc licence.

Links

-

'One singer referred him to another. He'd meet with these men and women and discuss lives and careers some forty years past and mostly forgotten; they appreciated his respect and inquisitiveness. Conversations would lead to questions that would lead to new singers and new conversations. My father filled hundreds of tapes, transcribed many of them… Recently, my father has approached me about helping with a project relating to these tapes… He asked if I'd be willing to help him "publish" some of these audio interviews on The Tofu Hut.'

Final Olympic round-up

Well, I thought the London 2012 segment of the closing ceremony was… OK.

The whole bus stop routine was underwhelming, and the presence of David Beckham seemed a bit random, but the moment when the bus opened up like a flower was a striking image, as was Leona Lewis raising up into the air with her frilly dress trailing down behind her. And while Led Zep isn’t my kind of music — or indeed remotely contemporary, by pop standards — it did just about manage to cut through the slightly oppressive grandiosity of the Chinese ceremony. So I’ll give it a solid 6½/10. For the London opening ceremony they need to bring that up to at least 8½, but for the time being I can live with that.

My sporting highlight of the games was Usain Bolt. No points for originality there. I know I said the other day that the sprint events were overrated, but for once they really lived up the hype. Watching someone beat the field by such a large margin and apparently so easily was almost surreal. It just shouldn’t be possible to do that.

I suppose I ought to name-check Michael Phelps, although as all his races were on in the middle of the night, I never really engaged with his story in the same way. Is he now The Greatest Olympian Ever? Well, I suppose he might be. It’s not that he won 8 medals in Beijing: sure, that’s incredible, but I still think the greatest individual achievement at a single Games was Emil Zátopek winning the 5000m, 10000m and marathon in 1952. But if you add the five golds from Athens, Phelps has completely dominated the swimming at two Olympics now, and that might be enough to secure his place as The Greatest. Apparently he’s planning to compete in 2012: if he could come to London and win another three or four golds, that really would put him in a class of his own.

Speaking of Zatopek: OMG, the Ethiopians in the long-distance running. To have Tirunesh Dibaba and Kenenisa Bekele both manage the 5000/10000 double was amazing. And particularly the women’s 10k and the men’s 5k; to see them sprint so easily away from the rest of the field at the end of a very fast-run race was almost as impressive in its way as Usain Bolt in the sprints. Bekele ran the last mile in under four minutes; I know the four-minute mile isn’t a big deal any more to a professional athlete, but to run one at the end of a fast 5000m… lawks.

And there’s Britain coming in fourth place on the medals table. Fourth! In Atlanta we came 36th. So three cheers for Christine Ohuruogu, Rebecca Adlington, Chris Hoy, Bradley Wiggins, Rebecca Romero, Nicole Cooke, and all the other medal winners whose names don’t spring to mind.

» photo credit: Beijing Olympics: Usain Bolt Breaks The World Record (Men’s 100 Meters) by Richard Giles, used under a Creative Commons by-sa licence.

A thought on the Olympics

While I wait anxiously to see whether London’s contribution to the closing ceremony is horribly naff, here’s a thought: since the Games are so huge and expensive to host, perhaps the future would be to split them up between lots of different places. Embrace the technology of global communication. That way, countries that could never afford to host the whole thing could bid to host just one sport.

For two weeks, there would always be some Olympic sport going on somewhere in the world; you’d be watching the boxing from Cairo, and then the broadcaster might cut to the sailing in Biarritz, or the swimming in Miami, or the cycling in Kuala Lumpur, or the gymnastics in Prague.

You’d lose something — that sense of the attention of the World all being focussed in on one spot — but it would turn it into a truly global event. And that might be quite special as well.

Nature’s Engraver by Jenny Uglow

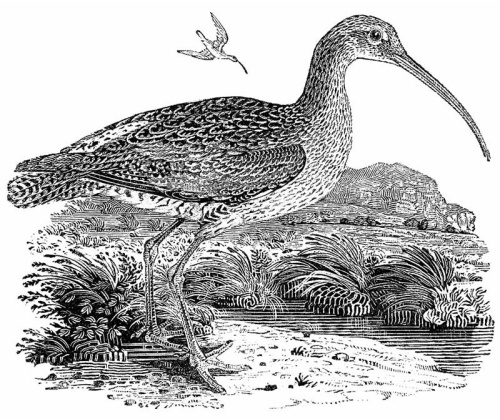

Jenny Uglow wrote the excellent The Lunar Men, about the Lunar Society that included Josiah Wedgwood, Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Priestley and Matthew Boulton. Nature’s Engraver is a biography of the wood engraver Thomas Bewick who, born in 1753, was just about contemporary with those men. He worked in Newcastle at a time when it was just starting to turn from a small provincial town into a major industrial city, but his subject matter is overwhelmingly rural. His masterpiece was his History of British Birds, which, quite apart from its artistic merits, was a landmark in the development of British ornithology.

The sensitivity with which he manages to reproduce feathering in an awkward medium like woodcut is remarkable. But the incredibly fine detail is even more apparent in the little decorative vignettes he produced which were used to fill gaps in the text of books. Engraved into the cross section of pieces of box wood, they are rarely more than 3″ across, but they are staggeringly finely worked. In the book, which is decorated with these vignettes throughout, they are printed at life-size; but since computer screens are simply not high-enough resolution to show them that way, here’s a 2″ section enlarged to show the workmanship:

The book is almost worth reading for the pictures, but Uglow also does a great job of evoking the period: the life of a provincial craftsman; the growth of interest in natural history that coincides, not perhaps by chance, with the coming of industry; radical politics and the response to the American and French Revolutions.

» Both pictures are taken from the website of the Bewick Society.