-

'Blondie looks like a regular penguin, except where he should be black, he’s bleached blond…. Blackie is a little different. Where she should be white, she is jet black—in fact, she is entirely black, beak to tail.'

Year: 2008

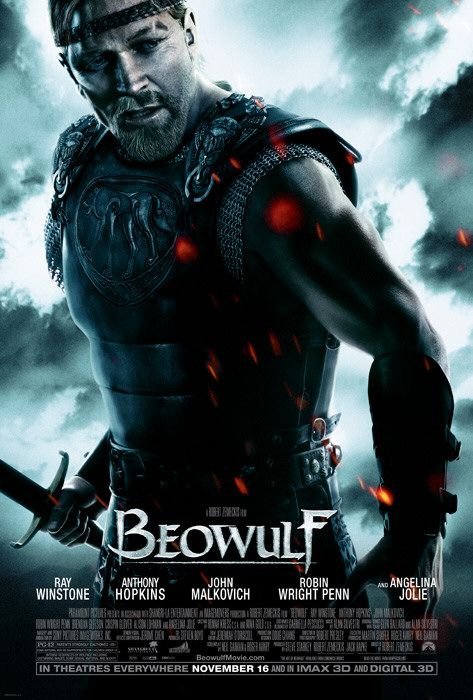

Pulp Beowulf

A link from C. Dale Young sent me to this article which is rather unflattering about a scheme to promote poetry in Seattle. What got me going, though, was this, from someone defending the scheme in the comments:

On comprehending poetry: you say “Poetry, by its very definition, is a difficult thing to write and to comprehend.” Certainly you can’t mean this, or perhaps you are simply uninformed. Since Mallarmé and especially since TS Eliot, perhaps, poetry’s hallmark is to be difficult, but again this is recent history given the history of bards: the Odyssey was the equivalent of a pulp fiction bestseller or action-adventure flick, ditto Beowulf and the Eddas. The Canterbury Tales, the Divine Comedy and Paradise Lost were intended to be blockbusters, not PhD theses. Shakespeare was not looking to mystify the objects of his love sonnets, nor is the work of Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, William Carlos Williams, Langston Hughes, Adrienne Rich, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Ntozake Shange, Sharon Olds, Saul Williams, Li-Young Lee or in fact most poets worth their salt supposed to be incomprehensible or even that difficult.

Now I agree with the basic point that difficulty is not an essential quality of poetry. But as someone with an interest in Anglo-Saxon poetry, I notice references in the media, so I have encountered this idea before, that Beowulf ‘was the equivalent of a pulp fiction bestseller or action-adventure flick’.

It is a fucking ridiculous comparison.

One version of it is based, as far as I can tell, simply on the kind of story it is: Beowulf is about a buff warrior-hero type who goes out and fights monsters, so it must be the Dark Ages version of Die Hard or Independence Day. Now I happen to believe this is a profound misreading of the poem, at least until someone makes a version of Die Hard which concerns itself deeply with the fragility, briefness and futility of human existence, or a version of Independence Day where the aliens win at the end.

But to properly try to refute that argument would be a difficult exercise, hedged around with qualifiers and uncertainty, because anyone who claims to know why Beowulf was written, who it was written for, how it was received or what kind of place it had in the culture is talking out of their arse.

Do you know how many surviving copies there are of long narrative Anglo-Saxon poems on non-Christian mythological themes? One. Beowulf. We assume that it is the only survivor from a rich oral culture of similar poems that were either never written down or have been lost — but we don’t know. And we certainly don’t know if Beowulf is a typical example, or how much it was changed when it was written down… or anything much at all, really.

And as for the statement that ‘the Canterbury Tales, the Divine Comedy and Paradise Lost were intended to be blockbusters, not PhD theses’: Jesus wept.

I mean Chaucer, maybe sorta kinda; Dante I don’t know much about, although even in C14th Florence there must have been more populist options available than the theological epic; but Milton? Seriously? He’s your example of poetry not having to be difficult? There aren’t many poems in English more self-consciously literary, less populist and more stubbornly unwilling to make life easy for the reader than Paradise Lost.

I think what annoys me so much isn’t the inaccuracy of these comparisons: it’s the fact that anyone wants to make them at all. I understand the wish to resist the ghettoisation of poetry as an recondite and überliterary artform. And it’s true that there is a long and valuable tradition of popular, accessible poetry, much of it ephemeral but some of real merit. But to compare Homer and Beowulf to action movies, or call the Divine Comedy a blockbuster, and think you’re doing them a favour… I just don’t get it.

Ageispolis

The Wooden Village by Peter Pišťanek

Or as the cover has it: The Wooden Village (Rivers of Babylon 2). That’s because it’s the sequel to Rivers of Babylon, which I read recently, and book two of a trilogy.

Rivers of Babylon, you may remember, follows a character called Rácz as he fights his way up from stoking the boilers of a big hotel in Bratislava to become a powerful businessman/crime lord. The Wooden Village focuses on one of the minor characters from that novel: Freddy Piggybank, who works in the hotel car park.

I didn’t think it was quite so successful; it suffers not so much from the absence of Rácz as a character but the lack of an equally compelling narrative framework. Rivers of Babylon had a whole cast of minor characters and subplots, but it was held together by the remorseless rise of Rácz; I don’t think the second book has such a strong core. The tone has shifted a bit, too; it’s still scathing and vulgar and energetic, but it seems to have lost the ferocious anger that powered the first book. It feels like a shift away from satire towards farce.

Anyway, here’s an extract. Freddy has just been told that the council is closing the car park and that he will therefore be losing his job:

Freddy sits there lifelessly. Only now does he feel the whole impact of his cruel fate. This is the end of Freddy. Life will not be worth living now. Where will he go? What will happen to him? Back to the brickyard? They’re laying off workers there. And his parents? What will his parents say? The vein in his head begins to pound dangerously. Freddy should be taking his medication, but he just sits there. I might as well croak, he thinks, full of self-pity. He imagines big headlines in the daily papers: BANKRUPT CAR PARK ATTENDANT DIES ON HIS LOT!.. HE ONLY WANTED TO LOOK AFTER CARS!.. ANOTHER VELVET REVOLUTION VICTIM? Yes, he’ll probably die here. The bitch from town council will read the paper and her conscience will bother her until she dies. Freddy wallows in his misery and rather pleasant self-pity. His chest heaves mightily a few times and he sighs with sadness. No, Piggybank realises, his death will not be headline news. Maybe some paper will have a little piece about it in the miscellaneous section: MENTALLY DISTURBED MISER DIES OF STROKE IN CAR PARK. Or something like that.

Freddy makes a decision. He will survive. He won’t allow his tragic death, a number one event for him, to become a source of entertainment fro some fool having his morning coffee. No! Freddy will fight. He will have revenge on this fucking government for this humiliation. He will live off crime. He will sink deep into the muck. He will steal and so on, until they catch up with him and lock him up in jail. And he’ll die in jail. As a sort of silent protest. As an example of what this government did to an honest businessman, Alfred Mešťánek, who only wanted to guard cars until his death and make an honest living. From now on, no wickedness will be wicked enough for Freddy!

I’d certainly recommend you read Rivers of Babylon, and if you enjoy that, you’ll probably enjoy this one too; it’s just not as good, I think.

» The photo of a sex shop in Bratislava is © Mark Pozzobon and used under a CC by-nc-sa licence. I don’t seem to have mentioned it in this post, but The Wooden Village has a lot of stuff about the sex trade, which is why the photo seemed relevant.

Links

-

“I spent the first 17 years of my life dirt-poor,” said Cassano, who was raised by a single mother in one of the most crime-ridden neighbourhoods in Italy and said he is certain that had it not been for football, he would have become a hoodlum. “Then I spent nine years living the life of a millionaire. That means I need another eight years living the way I do now and then I’ll be even.”

-

'On Boxing Day 1789, Franklin wrote to Webster in Hartford, returning the compliment: 'It is an excellent work, and will be greatly useful in turning the thoughts of our countrymen to correct writing.' He shared and appreciated his friend's prescriptivist distaste for vulgar idiom, and wanted to contribute further follies to a future edition of the work.'

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone by Saša Stanišić is my book from Bosnia and Herzegovina for the Read The World challenge. I actually had a different writer in mind — Ivo Andrić, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961 — but when I saw this in the bookshop I switched. Mainly because most of the books I’ve been reading are a few decades old, and it’s nice to find one which is fresh out of the oven (published in German in 2006; the English translation by Anthea Bell in 2008).

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone tells the story of Aleksandar Krsmanović, a boy who is growing up in the Bosnian town of Višegrad but flees with his family to Germany in 1992 to escape the war. Since Stanišić grew up in Višegrad and moved to Germany in 1992 as a fourteen-year-old, I assume it is somewhat autobiographical.

The blurb on the back cover compares Stanišić with Jonathan Safran Foer and David Foster Wallace, which gives you some idea of the kind of writer he is: a clever young man who isn’t afraid to leave evidence of his cleverness on the page. There are sections written in different voices, stylistic quirks, elements you might call magical realist, a bit of a book-within-a-book and so on. In fiction there can be a fine line between overtly clever and overly clever, and for the first few chapters I was a bit unsure which side of the line this book falls, but it won me over.

Here’s a fairly randomly picked passage:

My Nena went deaf the day Grandpa Rafik married the river Drina, face down. The marriage was legal because Nena and Grandpa Rafik had been divorced for years, something unusual in our town. After Grandpa Rafik was buried, they say she said at his graveside: I haven’t cooked anything, I haven’t brought anything, I haven’t put on black clothes, but I have a whole book full of things to forgive. They say she took out a stack of notes and began reading aloud from them. They say she stood there for a day and a night, and word by word, sentence by sentence, page by page she forgave him. And after that she said no more, and she never reacted to any kind of question again.

Nena Fatima has eyes as keen as a hawk’s, kyu, ket-ket, she recognises me before I turn into her street, and she wears headscarves. Nena’s hair is a secret — long and red and beautiful, she gave the secret away to me as we sat outside her house eating börek in summer and feeding the Drina with minced meat. Cold yoghurt, salted onions, the warmth of Nena rocking silently as she sits cross-legged. The dough is shiny with good fat. Nena rocks back and forth and lights a cigarette when I’ve had enough. I am the quietest grandson in the world, so as not to disturb her stillness and our sunset. Sultry heat gathers over the river and looks attentively at Nena Fatima, who is humming as she plaits her secret into a long braid. I don’t laugh with anyone as softly as with my Nena, I laugh with her until I’m exhausted, I don’t comb anyone else’s hair.

As I do the Read The World challenge, various themes are recurring; this is the third book I’ve read (along with My Father’s Notebook and The Kite Runner) which is written by a refugee, starts with nostalgic memories of the home country, and then describes the country collapsing and the refugee experience. It is much the best of the three, I think; I did genuinely enjoy The Kite Runner, but it is deeply emotionally manipulative, like watching a Hollywood film about a difficult subject by a skillful but solidly mainstream director. The kind of glossy film on a ‘brave’ subject which is daring enough to win a few Oscars but which you look back on a few years later and think… meh. How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone is a more interesting book all round; messier, more personal (I think), funnier, sadder. And while I don’t want to overstate the originality of it — it’s been nearly a hundred years since some bright spark invented modernism, FFS — it is at least less of a straight down the line conventional narrative.

» the photo is of the bridge over the Drina in Višegrad that is mentioned in How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone and is also incidentally the eponymous bridge in Ivo Andrić’s novel The Bridge on the Drina. The photo is © blandm and used under a CC by-nc-sa licence.