A sparrowhawk spotted at Borough Market:

Mind you, the only reason I was able to get a photo of it was that it’s stuffed. Presumably it’s there to discourage pigeons; you really don’t want them pooing on the pecorino.

A sparrowhawk spotted at Borough Market:

Mind you, the only reason I was able to get a photo of it was that it’s stuffed. Presumably it’s there to discourage pigeons; you really don’t want them pooing on the pecorino.

When I saw they were putting on Troilus and Cressida I thought it was about time I finally got round to seeing some Shakespeare at the Globe; previously the only thing I’d seen there was, randomly enough, a play about the writing of the US constitution.

I was about to say that Troilus and Cressida was one of favourite Shakespeare plays, but actually that’s putting it too strongly. It did make a particular impression on me when I read it, though: it’s funny and cynical and just interesting as a piece of literature.

The cynical/satirical aspect of it was probably particularly striking for me at the time because I must have read it fairly soon after reading Chaucer’s version, Troilus and Criseyde. Chaucer presents the story as a grand courtly romance; the telling of it is not without humour, but it is ultimately a serious story of love and loss and betrayal.

Troilus and Cressida is much more ambiguous, and there’s an interesting argument to be had about what exactly Shakespeare meant by it, but one thing it clearly isn’t is a grand romantic epic. One early edition of Shakespeare classified it with the histories, although it isn’t historical; another with the tragedies, although it doesn’t end with Troilus and Cressida lying dead among a heap of corpses either. Mind you, I suspect you could make an argument that that single editorial decision, 400 years ago, to divide the plays into three genres has been hugely unhelpful to our understanding of them.

For those of you who don’t know the play, it is set during the Trojan War and intertwines two stories: on the Trojan side, Troilus’s attempts to seduce Cressida, using her uncle Pandarus as a go-between, while in the Greek camp, Achilles is sulking in his tent and the Greek generals are trying to get him to start fighting again.

The Greek side of the story is unavoidably cynical: the generals treat Achilles and Ajax as useful idiots, tools to be manipulated into fighting. Ajax clearly is an idiot, Achilles slightly less so. The generals themselves are not much better. Agamemnon is given an opening speech of startling pomposity, in such a high style that it is completely opaque, Nestor is one of Shakespeare’s long-winded old men, and Ulysses is a scheming, manipulative cynic. When Achilles finally does come out to fight, he finds Hector unarmed and sets his men on him to kill him in cold blood, then takes the credit.

The programme for the Globe production made the plausible claim that T&C, which was previously largely neglected, has become more popular in the C20th because, since the Great War in particular, that kind of cynicism about the idea of military heroism has become more acceptable to us. And they played it for all the dark humour you might expect.

What surprised me a bit, though, was the treatment of the Troilus and Cressida part of the story, which was played relatively straight; they did their best to wring some emotion from it and give it the star-crossed lovers vibe. I have to say I didn’t read it that way on the page; their relationship consists of one night in bed, arranged by her uncle, and she is being unfaithful to him within 24 hours of being sent over to the Greek camp. There is never a hint of marriage, which is unsurprising in the medieval version but very unusual in Shakespeare. Yes there is some high-flown lovers’ rhetoric, but it is constantly undercut by the busy-bodying and innuendo of Pandarus. Even at their first expressions of love, she admits to having played hard to get and then worries that by admitting it she will have lost power over him — not the profoundest kind of deceit but not exactly Romeo and Juliet either.

For me, just as the war parts of the play read as a parody of the grand heroic style of Homer and of medieval chivalric romance, the love story is a parody of medieval romance — or indeed of Romeo and Juliet.

Anyway. Questions of interpretation aside, I did enjoy the production. One of the nice things about the Globe is seeing theatre performed without the aid of lighting, amplified music and elaborate mechanised sets: just performers on a fairly plain stage in daylight having to hold the audience by, you know, acting.

Matthew Kelly played a rather camp Pandarus with a bit of a thing for Troilus, which I thought worked well to provide some explanation as to why he was setting him up with his niece. And it fitted in with the general homoeroticism of all those buff, bare-chested Greek warriors, and the possible relationship between Achilles and Patroclus.

Thersites, the fool character who spends the play providing barbed commentary on the action, was played rather too broadly as a clown for my taste. It wouldn’t surprise me if the clowns and fools gave pretty broad performances in Shakespeare’s time as well — the fact that they were treated as specialist roles certainly suggests it — but I find I have a limited tolerance for gurning.

The battle scenes were a bit laboured, but I don’t know if there’s a simple solution to that, given that you don’t want the actors to actually hurt each other. I also went to see the play early in the run, and the sword-swinging may start looking a bit more natural when they’ve spent more time doing it.

Sorry for the slight hiatus; it was a combination of the cricket and Dragon Quest: the Chapters of the Chosen. But there’s a pause in the cricket*, so I’ll just quickly round up a few of the things I’ve been to see recently.

Firstly, the big Baroque exhibition at the V&A, which I went to see a few weeks ago and actually closed yesterday. This is exactly the kind of exhibition that the V&A does a superb job with, and I was glad I went, but I couldn’t work up much enthusiasm for it because, well, it’s the Baroque. It’s the aesthetic of wealth and power, of an exquisitely crafted, gilded boot stamping on a human face forever. I didn’t warm to it.

There were interesting items and impressive ones, but not many were likeable; almost none triggered the acquisitive itch in me. The slight exception was actually a video reel of Baroque buildings. Craftsmen obviously struggled to capture the grandeur, ambition and megalomania of the Baroque in something like a candlestick or a side-table — although it didn’t stop them trying — but if you’ve got a whole church to work with, or a palace or an opera house, you can produce something magnificent.

And I suppose you can argue that once you’ve got your church or your palace, you need some suitably pompous candlesticks and side-tables to match the decor. I still can’t get excited about going to look at them in a museum.

A more enjoyable exhibition was BM’s Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur. These are paintings that are in a style that I associate with Persian miniatures — and of course the Mughals were Persians, more or less — but on a much large scale.

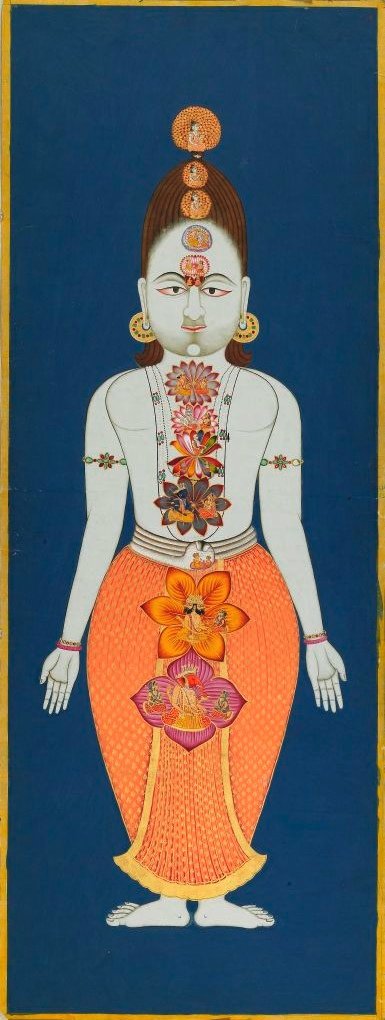

Different Maharajas commissioned different works. The exhibition starts with paintings of court life, mainly represented here as lounging around in the palace garden surrounded by scantily clad women. Then as, we move into scenes from Hindu mythology — some of them looking remarkably like the first paintings except with Shiva sitting in a garden instead of the Maharaja of Jodhpur, but others with more dramatic subjects from the Ramayana. And then it shifts into a more esoteric, mystical tradition within Hinduism, with paintings of the creation of the universe from nothingness, spiritual maps of the universe, symbolic maps of the human body with chakras and so on.

The pictures were attractive, never a bad thing, as well as being interesting. And the attempts to represent the unrepresentable were beautiful and more successful (whatever that means) than most Western equivalents I can think of.

I also went to the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition (“now in its 241st year!”). It’s always slightly more enjoyable than I expect; apart from anything else, it’s always interesting to go to an art exhibition where everything has a price marked on it. Vulgar of me, I know. But there’s just so much of it that you’re suffering from fried brain by two thirds of the way through.

And on the subject of art prices, check out this link: ‘If Famous Architecture Were Priced Like Paintings, a Le Corbusier Would Cost the Same as the Entire American GDP‘.

*after a heroic win for England at Lord’s, the first time we’ve beaten the Aussies there for 75 years. I could probably find quite a lot to say about the first two matches in the series — that 75-year losing streak is a fascinating subject in itself — but let’s stay on topic.

»The picture is Chakras of the Subtle Body, 1823, © Mehrangarh Museum Trust.