More from the London Film Festival. Le Moine is a film of the 1796 gothic novel The Monk by Matthew Lewis. It’s a long time since I read the book, but I remembered that it was an overblown, melodramatic, sensational novel, so naturally I was keen to see a film version of it.

It lived up to the melodramatic tone of the book, anyway, although it didn’t really try to be shocking by modern standards; they could easily have incorporated a lot more graphic sex and violence if they wanted to, especially since they were messing around with the plot anyway.*

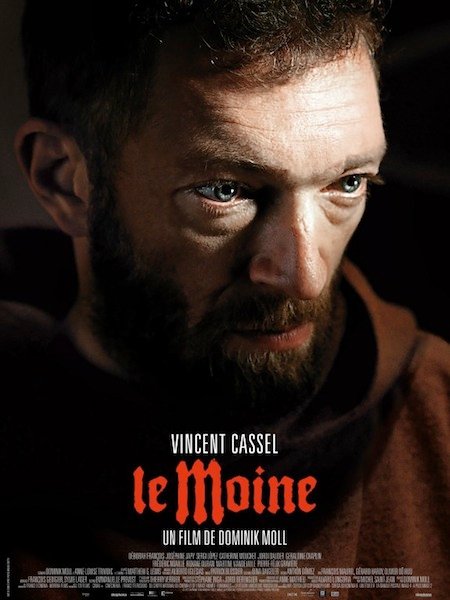

It reminded me of Black Swan, actually: a fundamentally silly paper-thin melodrama masquerading as an art film. It even has Vincent Cassel. It’s set in [early C17th?] Spain, and it looks beautiful, with lots of medieval buildings, arid Spanish landscapes, winding back alleys, and even some gorgeous frocks. Plus an amazing scene of a religious procession through the streets of the town. And the broody Cassel holds the film together as the monk. But no amount of intense acting and beautiful camerawork can disguise the basic ludicrousness of the plot.

Now personally I enjoyed Black Swan, although I know a lot of people hated it, and I enjoyed The Monk. But I think in both cases you need to go in with appropriate expectations: I think a few people went into Black Swan expecting a serious psychological thriller and were irritated to find themselves watching an expensively made horror movie. Whereas I went in expecting it to be a piece of high camp, because I had seen the trailer, and I enjoyed it for what it was. And I enjoyed The Monk on the same terms.

* something I didn’t realise while watching the film — I don’t remember the book well enough for that — but while checking the novel’s synopsis on Wikipedia. I don’t think it’s the kind of book that invites reverential treatment, though.